A Lord of Revolution

When Leopoldo López ’93 H’07 arrived in Gambier in 1989, he was a young man with a penchant for mischief-making. During his freshman year, López bought a cheap, used motorcycle in Mount Vernon and zipped down the corridors of Lewis Residence Hall. Rob Gluck ’93, a friend and classmate of López, recalls that López, who had a passion for boxing, would organize matches in the Lewis lounge. López “brought people together,” Gluck told the College in a 2014 lecture.

Twenty-eight years later, López has carried that fighting spirit into a larger, and much more contentious, ring. A leader in the opposition movement to Venezuela’s socialist president, Nicolás Maduro, López is serving a 13-year, nine-month jail sentence for political dissidence. López, the most well-known of Venezuela’s 114 political prisoners, was first arrested in 2014 for participating in a wave of protests across the country that left 44 dead. Maduro’s government has shifted much of the blame onto López, accusing him of inciting violence via subliminal messages.

Years after the protests, López remains a polarizing figure. To most of the Kenyon community and America at large, he is a champion of democracy, and, as Gluck said, still “bringing people together.” To his enemies, such as the state-run news organization teleSUR, he is a threat to the government, fighting with words instead of gloves. From a precocious student to a controversial politician, López has embarked on a journey fraught with acts of opposition that began right here on the Hill.

The Kenyon Years

Before he was the face of a revolution, López became a face of Kenyon, featured in a series of videos filmed by the Office of Admissions to capture the “Kenyon experience” for posterity and prospective students.

“I like that it’s very easy to be extremely active,” a young López says in the film. “At the same time it’s very easy to be extremely apathetic. The school can help you out, and students get very excited and involved.”

Prior to taking to the streets of Venezuela, López was known for organizing campus demonstrations. In 1990, he and a group of friends pulled the fire alarms of several Kenyon residence halls to protest America’s invasion of Kuwait in the first Gulf War.

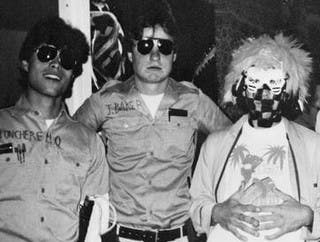

Lopez (seen on the left) dresses up as Poncherello from the NBC show CHiPS for Halloween during his time at Kenyon.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the ReveilleLópez also promoted environmental consciousness. As a first year, he began Active Students Helping the Earth Survive (ASHES), an environmental organization that endured a few years after López graduated, but is now defunct.

A sociology major, López also took classes in economics, political science, and the Integrated Program in Humane Studies (IPHS). Although he was put on academic probation as a first year, López later surpassed the rest of his peers.He graduated cum laude and was awarded the George Herbert Mead sociology and Richard F. Hettlinger IPHS awards. “He was an outstanding student,” Professor of Religious Studies Royal Rhodes told the Collegian in 2014.

After Kenyon, López attended the Harvard University Kennedy School of Government. Upon graduating in 1996 with a Masters of Public Policy, he would come home to a country embroiled in political and economic tensions.

Beginning a Movement

Before beginning his political career, López held a variety of positions at Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), Venezuela’s state oil company, and taught economics at Universidad Catolica Andres Bello. It wasn’t until he co-founded Primero Justicia, a center-right civil society (and later, in 2000, a full-blown political party), that his name became known in the Venezuelan political circuit. His big break came in 2000, when he was elected mayor of the Municipality of Chacao, an administrative subdivision of Chacao and a middle class stronghold.

López received numerous awards during his mayoral run and gained increasing support in both his community and in Venezuela at large. It was because of this support that many think the legal attacks on López that followed his mayorship in 2008 were politically motivated. The initial charges were filed when a comptroller discovered López accepted a grant of $12,000 that his mother had issued from PDVSA to Primero Justicia while he was still working there in 1998. While Primero Justicia was not a political party at the time, López was nevertheless banned from holding office from 2005-2008. Many, including the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, took exception to the Venezuelan government’s ban in light of the technical, if not murky, legality of the grant.

López encouraged his supporters to take to the streets to show their dissatisfaction with the current political regime. When protests started, López was the leader of the Voluntad Popular, a centrist political party that is part of the Democratic Unity Roundtable Coalition (DUR). DUR was designed as a political coalition of different parties ranging from center right to left wing that has helped unify the opposition against Maduro’s government.

In the midst of the 2014 Venezuelan protests, an escalation of tensions led to widespread clashes between anti-government activist groups and government forces. In their initial months, the conflicts resulted in over 4,000 arrests and 44 deaths. Believing that López incited public violence, prosecutors issued a warrant for his arrest on February 14, 2014.

A video of López’s arrest, and the rally that preceded it, was streamed at “A Fight For Freedom,” a 2014 lecture sponsored by Kenyon’s Study for the Center of American Democracy. In the shot, the streets are crowded with people, and there is little, if any, room to move. When López chants “Si se puede,” the crowd chants with him.

López was eventually sentenced to nearly 14 years in Ramo Verde, a military base in Los Teques. “Our government wants to crush our aspirations and make us believe that this fight is hopeless,“ López said in a New York Times Op-Ed published just 15 days after his sentencing. “They want us to surrender. But we cannot afford to surrender, for he who tires, loses.”

Most, including an EU delegate to the trial and the United Nations, consider López’s trial to have been unfair, in part because the defense was allowed only three hours to present its case. The prosecution was allowed 600. Franklin Nieves, a prosecutor against López, later denounced the trial and fled to the U.S. after accusing the Maduro government of corruption. He called the case a “farce” on CNN en Español and accused the government of fabricating the charges.

Even so, on February 16, 2017, a Venezuelan court upheld López’s 13-year-and-nine-month sentence, the maximum sentence for political dissidents. There is currently no release date in place.

Between a Martyr and a Political Opponent

In a country with the third-highest murder rate and the highest rate of inflation in the world, public opinion of the government is waning and faith in opposition leaders like López is on the rise; according to an Instituto Venezolano de Análisis de Datos (IVAD) poll, 59 percent of respondents answered “Yes” to the questions “Do you agree Leopoldo is innocent and remains in prison for political reasons?” and “Do you agree the government is transforming into a dictatorship?”

With faith in the government disappearing, López is becoming a symbol of strength. “He’s a voice for millions,” Adriana López Vermut, López’s sister, said in Beyond Politics, a video Mia Barnett ’15 produced for her American studies senior exercise. Yet millions are taking up the mantle to be the voice for López. The #freeleopoldo hashtag, started by López’s classmates at Kenyon, advocates for López’s release from Ramo Verde.

“Freeing Leo,” however, might be difficult to accomplish, according to Assistant Professor of Sociology Celso Villegas. Villegas says that López has gained “symbolic power” since his imprisonment, making it less likely for López to be released or even executed. If released, Villegas said, López would threaten the political hold of Maduro’s government. If executed, López would become a martyr, rallying support for the opposition. So López remains in prison, subjected to various punishments.

In Beyond Politics, López Vermut says her brother is treated like a “high-level terrorist.” During the instances in which López has been called to trial, government officials remove him from his cell in the middle of the night, close highways while they transport him in military-grade tanks, and keep him waiting for upwards of six hours in a “dungeon”-like cell before presenting him before the court. Hearings are lengthy, usually lasting from three to 10 hours.

Treatment is not much better inside the prison. In Beyond Politics, López Vermut describes a time when prison guards threw excrement and urine into her brother’s cell and suspended water and electricity so that he could not clean the mess. At any confidential meeting between López and his lawyers, a prison guard remains inside. Because he is in solitary confinement, López is allowed outside of his cell for only an hour every day at 6 a.m., before any fellow prisoners are granted access to the yard.

López’s correspondence with people outside the prison is highly supervised. Visiting rights are restricted so that only immediate family — his wife, children, parents, and sisters — are allowed to meet with him. But visiting rights are sometimes suspended without explanation, and López’s family can be barred entrance for two to three weeks at a time.

“I’m waiting in Ramo Verde so that the director of the jail and the government can tell me why we can’t see Leopoldo and why he continues to be isolated,” López’s wife, Lilian Tintori, posted on Twitter in May 2015. “What is happening is a permanent violation of our human rights. Not just with my family, but with all of Venezuela.”

According to Human Rights Watch, prisoners in Ramo Verde awaken to the “alarm clock” of prison guards chanting “Chávez is alive, the fight continues!” — an attempt to demoralize the prisoners.

López, seen on the left, poses with his advisor, Professor of Sociology George McCarthy, at the Village Inn.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Greenslade Special Collections and ArchivesTo many, López’s incarceration reveals Venezuela’s failure to uphold democratic principles. Jared Genser, López’s lawyer and founder of Freedom Now, an independent NGO that works to free prisoners of conscience (anyone imprisoned for political or religious views, sexuality, or race), told U.S. News and World Report that “only in an authoritarian regime does an opposition leader get a maximum prison sentence on completely false charges for exercising his rights to freedom of expression, opinion, and association.”

Professor of Sociology George McCarthy, who was López’s faculty advisor at Kenyon, views the Venezuelan government’s response to dissenting citizens as unethical. “If the government disagrees with him, I think the government should argue intelligently against his views,” McCarthy said, “but you don’t put a person in prison to shut them up. It’s not democratic.”

McCarthy hopes that, despite the cruelties inflicted upon him, López’s time spent in prison inspires him to more adamantly fight for his political cause. The propensity of political prisoners to gain strength during incarceration has been coined the “Mandela effect” — named for Nelson Mandela, who served 27 years in a South African prison for anti-apartheid activism before becoming president. López Vermut has observed this type of behavior in her brother. “His face and his demeanor was very much who he is,” she said, describing a visit on the one-year anniversary of her brother’s imprisonment. “Being alone has allowed him time … to get spiritually strong and you can actually see it in him.”

Lilian Tintori, López’s wife, fields questions from reporters during a speech in the Federal Senate.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsVillegas recognizes that the “Mandela effect” materializes frequently in the stories told about opposition leaders. “There is an interesting trope among opposition leaders and there’s particular sorts of plot points in the story that map practically perfectly over the story that Leopoldo López’s sister will tell about him and the way perhaps he’s describing himself,” he said. Villegas referenced Benigno Aquino Jr., the Filipino opposition leader during the era of martial law, who was assassinated in 1983. Aquino’s assassination galvanized support for the opposition. Following Aquino’s death, his widow, Corazon Aquino, took the mantle of opposition leader — a position that López’s wife Tintori also embraced.

Since López’s imprisonment, Tintori has travelled around the world asking governments to more aggressively condemn human rights violations in Venezuela. In the U.S., Tintori met with former Vice President Joe Biden and the Trump administration. In a Tweet from February 15, President Donald Trump — posing with Tintori, Vice President Mike Pence, and Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) — called for the Venezuelan government to release López “out of prison immediately.”

Not Such a Rosy Picture

According to a report by Reuters, López won his district of Chacao, Caracas with 81 percent of the vote, serving two terms before he was 30 years old. In the rest of Venezuela, however, López has evaded support. Kenyon- and Harvard-educated, wealthy, and a direct descendant of Latin American independence hero Simón Bolívar’s sister and Venezuela’s first president Cristobal Mendoza, López’s “blue blood” distances himself from most of the country.

While most coverage of López in the U.S. paints him as a hero, there has been discussion about whether he truly lives up to his Bolívarian democratic pedigree. In 2002, López and his father were tied to the attempted coup of former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. The coup occurred amid general strikes and protests both against PDVSA and for the existing Chávez government. Tensions came to a head when a group of business and military leaders took Chávez into custody and proclaimed a new government headed by Pedro Carmona. This announcement, dubbed the Carmona Decree, dissolved both the National Assembly and the Supreme Court, as well as the entirety of the 1999 constitution.

López’s father, Leopoldo López Gil, was at the ceremony in the presidential palace where the Decree was signed by a number of supporters. According to Roberto Lovato’s Foreign Policy article “The Making of Leopoldo López,” López Gil says he only signed an attendance sheet, and that “none of us there signed any ‘decree.’” However, a video of Carmona signing the decree shows Daniel Romero, Carmona’s attorney general designate, calling attendees to “sign the decree that was just read in support of the process.”

Yet López promises he had nothing to do with the coup itself. He did protest, but anti-government demonstrations ranged from nonviolent attempts to get Chávez to resign, to more extreme measures. López expressed in numerous interviews his desire for a peaceful and ordered resignation and transfer of power, but also postulated the need for a post-coup transition government.

López’s family’s link to the coup does little to boost his popularity among skeptics. The coup ultimately failed and is massively unpopular among Venezuelans. According to the leading Venezuelan poll organization Datanalasis, 90 percent of Venezuelans view the coup unfavorably.

López’s detainment of Ramón Rodríguez Chacín, Chávez’s Interior Minister, also remains controversial. López and Henrique Capriles Radonski (another founding member of Primero Justicia) arrived at Chacín’s home, accused him of causing the deaths of 19 protesters, and conducted a citizen’s arrest with the help of the Baruta police. The arrest was unsuccessful, as Capriles was the mayor of Baruta and unlikely to be jailed in the town he controlled. López later admitted that he thought the arrest was a mistake but told reporters on the scene that “President Carmona knows of this arrest,” indicating another possible collusion with the coup government.

López also isn’t immune to criticism at Kenyon. In a September 2015 Collegian Op-Ed, Isabella Bird-Muñoz ’18 criticizes the campus’s support for the politician. She cites an article by Mark Weisbrot in CounterPunch that offers an on-the-ground look at the 2002 protests. While international coverage usually depicts these demonstrations as a populist “general strike,” Weisbrot reports that the tensions divided Caracas sharply. In the wealthy parts of Caracas, López’s seat of power, workers found themselves shut out while their employers protested. “In the western and poorer parts of the city,” he says, “everything was normal and people were doing their Christmas shopping.”

Although Bird-Muñoz confused the 2002 protests with those of 2014, accounts of that period are not much different. Most López supporters in these rallies continue to be those of his first political constituency — the bastion of upper-middle-class liberals that appeals to sensibilities around the world.

López, the direct descendant of Simón Bolívar’s sister, amassed a large following in Venezuela as part of the political opposition movement to President Nicolás Maduro.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsBut these claims against López are often refuted as circumstantial or meaningless in light of abuses of free speech by Maduro’s government. Regardless of these controversies, the ever-worsening economic and political tension in Venezuela means that a specific knowledge of the opposition — and what López and his comrades are fighting for — is becoming increasingly essential in Venezuela’s political climate.

With over 10 years left on his sentence, López is far away from attending a reunion weekend back on the Hill. Backed with support from around the globe against a regime that labels him a terrorist, his future is unclear. But López is a fighter, and fighters don’t quit in the final bout. He may be down, but he’s not out.