An Hour with Josh Radnor

Almost 10 years after Liberal Arts, two Collegian Magazine writers sit down and discuss Kenyon with the movie’s maker, Josh Radnor

In a pandemic present, many of us found solace in gloriously pictorialized pasts. This spring semester began markedly different from others, and we itched for a glimpse of a Kenyon as it had been in times past. On the eve of its tenth anniversary, we gave the film Liberal Arts another watch.

Liberal Arts, directed by Josh Radnor and released in 2012, follows Jesse Fisher, a 35-year-old college admissions officer (played by Radnor) as he returns to his alma mater (a nondescript college, filmed on Kenyon’s campus) to see off his beloved former professor into retirement. Upon return to campus, Jesse is temporarily discombobulated and a recognition of the distance from his college years sets in. Jesse must reckon with his age and maturity in relation to the students, particularly towards a sophomore played by Elizabeth Olsen to whom he feels pulled.

Both of us had watched the movie as eager prospective students. Upon second viewing, with some time at Kenyon under our belts, the movie struck a different chord. “How might Radnor reflect on the movie?” we wondered. We had the chance to ask him himself in an interview this April.

Radnor graduated from Kenyon College in 1996 as a drama major. After completing his MFA, he rose to success steadily, taking a break from Broadway for a lead role in the sitcom How I Met Your Mother until 2014, and then a directorial debut in 2011 with the film happythankyoumoreplease. Liberal Arts — also directed and starred in by Radnor — followed swiftly after, premiering at Sundance in 2012 to a pleased crowd and mostly satisfied reviews.

Peter Rutkoff, one of the founders of the American Studies department at Kenyon, taught and mentored Radnor throughout his time on campus. Says Rutkoff of Radnor: “Yeah, it’s just simple“ he’s a smart guy […] He’s serious, he’s well-read, and he loves literature.” The relationship between the two has continued as a friendship beyond Radnor’s graduation. In Liberal Arts, the influence of this personal relationship is clear in Radnor’s characterization of the mentoring professor Peter Hobart (played by Richard Jenkins). Asked about his proximity to the character, Rutkoff said: “Look, you know, [Radnor] didn’t say that I was modeling the character after you. But he said, ‘I want you to read it and tell me what you think about it.’” When we spoke to Rutkoff, he alluded to other inspirations that Radnor may have picked up, including the influence of the late Professor of Drama Harlene Marley on Allison Janney’s character, Professor Fairfield (Radnor set the record straight when we put this theory forth in our conversation with him).

The pair maintain contact and Rutkoff is a fond reader Radnor’s email newsletter, Museletter, in which Radnor shares with subscribers his band’s music, suggestions, and musings.

FRED AND FLANNERY: How do you feel the movie has aged even nearly 10 years after its initial release?

JOSH:

I look back very fondly on the movie. I have a line in my first film, happythankyoumoreplease about how essentially every five years you look back and realize what an idiot you were five years ago. I’m sure there’s certain things that if I were to go back and look at it, I would maybe cringe or blush at certain things. But then I know that I really gave it my all and it was really something that was burning inside of me. The story came on very swiftly. I felt like I was really dropped into the story. I was very invested in the characters. I can always tell when I’ve got my teeth in something and it’s working.

It’s like — not to get too mystical about it — but it’s a little bit like you’re taking dictation with writing. Like the characters just become very alive in your imagination and they start unspooling in front of you. And that was how that was how it felt.

And also the crew. I remember, the crew really bonded in Gambier. A lot of them had never been to Ohio and had not heard of Kenyon. By the end they were weeping and saying, “I want to send my kids here.” They really fell in love with Kenyon. So I was so happy to be able to share something that I love so deeply with people both, in the experience of making it and the experience of bringing it out into the world. It is certainly a campus that is a production designer’s dream because you don’t have to do all that much.

But anyway, as to the question of how it aged, I think there’s something quite fascinating here. When people would talk about this film, there were a couple people that mentioned the film or put it on lists, you know, May-December romance movies or college movies. And a couple people have said, it’s the romance between a 35-year-old man and a 20 year-old college student, even alluding to the fact that it was a sexually consummated relationship, which, if you watch the film — and I hate to spoil this for people — that’s not what the movie is. In fact, it’s playing against all those tropes, you know.The reviews were largely good for Liberal Arts, but I got accused by a couple of male critics, older male critics, who said that I lost my nerve as a writer by not having them get together. And I always felt like that was actually what was the most special thing about the movie, was that ultimately Jesse pulls away.

The normal trope in those movies is that the older man and the younger woman get together, and they have lots of sex, and then they part and they’ve all learned something and whatever. But I thought, “It might be more interesting, what if they didn’t? What if they had to really examine what was drawing them for each other and find a different way of relating and find some peace with that?” I had a couple people come up to me — some people I know really well, some people I didn’t know very well — who had stories about, you know, professors, or older mentors or men who did not make that decision with them. And it was really, it took them a long time to deal with the trauma of it. And so in some ways — not to pat myself on the back too much — I feel like the movie has aged quite well, in that regard, in light of how the culture has shifted around power dynamics and you know, age differences and consent issues. I’m actually really proud of the movie in that way. I’m not really ever trying to be a political writer, but the personal is political. So I think that a lot of the things that I was dealing with, just because they were interesting to me at the time, are really central to a cultural dialogue that we’re having right now. So I’m quite proud of the movie in that regard.

FRED AND FLANNERY: Professor Rutkoff mentioned how influential Harlene Marley was to you as a student. Was the Alison Janney character based on your drama professor Harlene Marley?

JOSH:

Yeah, that’s not true. I should correct that. In hindsight, it might have been kind of unconscious. But what happened was, I was directing Alison and then I kind of told her to really lean into the language and not be afraid to be a little theatrical with the way she talks and Allison said, “Oh, like Harlene!” because we both had her as a professor. And I said “Yeah, yeah sure.” So Allison kind of took that and ran with that.

But you know I did not conceive of it that way. That said, I’m sure there was some of it because Harlene — and this should be said — was not a misanthrope and she was not a cynic at all. I mean, she was the best. I mean, I tear up when I think about her and I cried real tears when I went back to Kenyon for her memorial. She was really, really special and she was hilarious and dramatic and wore terrific rings and jewelry. Yeah, you know, she was just a great woman and professor.

I did take a running gag — which came from Rutkoff and it came from Harlene — that they both really, really hated faculty meetings. And Harlene was the first one to tell me that and I asked her, “Do you like faculty meetings?” and she said, “No they’re my least favorite thing about the job.”

FRED AND FLANNERY: What was your experience like as a student?

JOSH:

I was a drama major, but I went to the National Theatre Institute my junior year, so I got a lot of my theater credits there, even though I took a decent amount. I took a lot of history of theater with Tom Sturgeon and 17th and 18th Century with Sturgeon, and so I took a lot of more academic classes. I took playwriting with Wendy [MacLeod]. But I took a huge host of other classes — philosophy, history and English. So I never felt like I was siloing myself in the theater department. I felt like I was getting a really broad liberal arts education. I really wanted to be an actor and I spent a lot of time doing plays and you know, Fools on the Hill. I went to NYU to a grad acting program at Tisch right after and that was really my conservatory training around the clock, and technique and all that.

So I was at Kenyon more to get the philosophy classes and the English classes and the history classes. That was lighting me up at Kenyon just as much as the plays were.

Peter and I had a really special connection, especially around my junior and senior year. I took him sophomore year, but then I think I took him either junior or senior year, maybe junior year, and then we were just friends for the rest of the time. And he was also incredibly supportive, like he would come to see my plays. He was always wildly complimentary. And that’s such a special thing, when professors come see your plays and they come to your stuff and support what you’re doing outside the classroom. Harlene and Peter were probably the two most impactful teachers I had there — or the ones I was closest with, at the very least.

I remember being very excited about books. I was influenced as much by fellow students as I was by professors. I remember, I fell in with a really funny, smart, intellectual gang. You know, some of them were in my freshman dorm. I was on the third floor of McBride. And a lot of my friends — my friend, Kip Conlan — listened to Leonard Cohen and Tom Waits, and knew more Bob Dylan than I knew.

So there were music influences. And my friend Mark Hughes was a huge reader. They were reading John Cheever. The fun thing about Kenyon is like, there is peer pressure, but it’s a kind of intellectual peer pressure, where you want to feel like you’re part of the larger conversation going on. And I had some catching up to do in that regard, but I wanted to be somebody who was a good writer, and to be a good writer, you have to be a good thinker. You know, writing well is thinking clearly. And I found that I was a much clearer thinker when I left Kenyon than when I got there. I will say I had to do some remedial work around feelings.

I think there’s a premium placed on the intellect — obviously — in college. And then when I got to NYU, and subsequently just living life was much more about reclaiming — you know, I don’t know, it’s a little cliche to say — but like more matters of the heart, and marrying the intellect with the feeling, all of which has served me as an actor. I think when I got to NYU, I was a much more heady actor than I am now. But that’s all just been a process.

FRED AND FLANNERY: Was the movie meant to be a love letter more to Kenyon or to the entire collegiate experience?

JOSH:

Well, I would say anything that I make is going to be personal in that it came from me and I cannot speak for everyone who went to Kenyon or everyone who went to college, nor would I ever attempt that. The cliched writing advice holds true, though, that the more specific you get, the more universal you get. And I think certain things were very specific. You know, some of Jesse’s sentiments are things I buy and other ones are not.

Certainly Jessie — I hope this doesn’t sound obnoxious — he was less successful than me. I was on a TV show when I did Liberal Arts, I wasn’t lost and living in New York City. And we actually cut a whole storyline of Jessie with his friend back in New York, but the way we cut this together he looks pretty lonely like he doesn’t have a lot of community, and that was not my life. You know, I was surrounded by people. So I do think it was personal and I wasn’t trying to speak for everyone.

But what I do think where it strikes a universal chord is everyone is shocked when they turn 35 and they still feel like they’re 19. And then you get shocked when you turn 45 and 55 and 65. I mean, time starts bending in all sorts of strange ways. I went back to Kenyon to show happythankyoumoreplease, and everyone was suddenly calling me Mr. Radnor. And I was like, “I was just here, like, five minutes ago, how did I become an elder?” And time still continues to be strange. To me, aging is a very almost psychedelic process. It’s very, it’s just trippy.

FRED AND FLANNERY: We were reading your archived newsletters, and found this quote: “Can you imagine what lazy callous loves and immortality would make us?” How would you define your relationship with mortality and the swiftness of time? How have you reckoned with mortality? And have things gotten better for you as you’ve aged?

JOSH:

I would say, things have gotten better for me since I’ve aged. I can say that. Certainly, I enjoyed my 30s more than my 20s, and I’m enjoying my 40s more than I did my 30s. So that is encouraging… you have to fight this cultural lie that says that young is better. And that youth is enviable, and we really fetishize youth in such a really destructive way in this country. But while I’m really enjoying being older, there still is some sadness or melancholy that creeps in around this feeling. And this is something Jessie says in the movie that I really dealt with, which was when you’re in college you just have so many options ahead of you — you can even pick a different major — like, “Oh my gosh, what is my life gonna look like?” There’s so many ways that it could go. And then your life begins to happen. And you make these choices. And these choices have consequences. And there’s this kind of narrowing that starts happening, where you feel like you’ve got to really stand by these decisions, and some of which you regret. So things get a little more grooved. And there’s a little sadness to that, because you realize that you’ve made choices, and those choices have consequences. And some of them were unintended, or some of them you wish had gone a different way. I am in, I guess I’d call it a minority of people that knew what I wanted to do pretty young, and I’ve done it, but I’ve also branched out and I’ve done all these other things. I mean, I studied to be an actor. I didn’t study to be a writer-director.

I’m now a musician. And I certainly did not study to be a musician. I really think like, trying new things, and daring to get out of your lane — what Robert Redford called starting from zero — I really feel that that’s the secret. It’s kind of the fountain of youth because we tend to lean into the things we’re good at as we get older and we get rewarded for it so we stop risk taking.

So that is something that I did take from Kenyon, this spirit of adventure and being bold about trying new things. And also I think my many years as an actor really taught me to get comfortable with failure and humiliation. You know, I’ve failed and have been humiliated at a very big public level in various ways. And it hasn’t killed me and in fact it’s just kind of showed me that’s not really something to lose all that much sleep over, like no one remembers anyway, so just move on.

FRED AND FLANNERY: I’m always thinking about what I would want, what I’m going to miss the most or what I’m gonna be grateful for about Kenyon that I’m not now and that I should be or whatever. Were there moments like that for you? When you came back to film the movie that you were like, “Oh my God, this is what I was missing out on when I was here.” Did you have new revelations about Kenyon when you were making the movie?

JOSH:

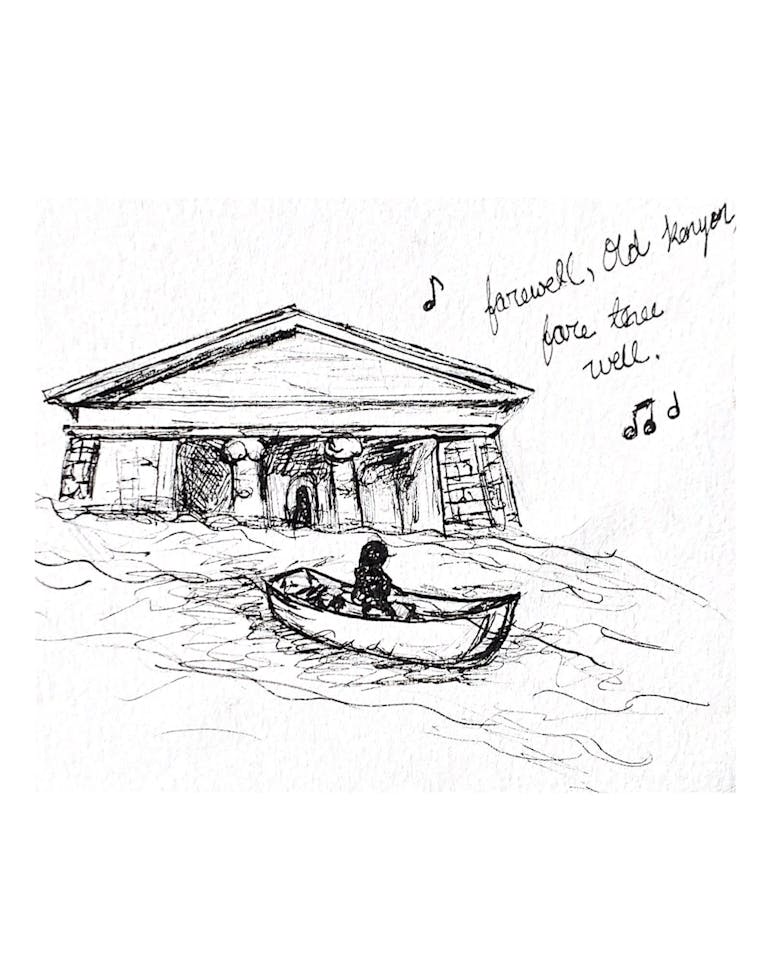

Well, I think the thing you’re describing is actually a really funny and almost like, under-discussed phenomenon of Kenyon, which is that you’re nostalgic for it even while you’re there. And there’s the feeling that you know you’re gonna not be there forever. And you kind of mourn it while you’re there.

I always felt like I was always projecting forward, almost like I was watching myself go through college. Zibby kind of had that thing. Like, she’s, she’s hovering over herself. And I remember friends would talk about, you know, if someone mentioned, like graduating or being out of school people would be like “Don’t say that!” as if it was like this curse, that we were gonna have to leave this place one day. It’s painful and beautiful all at once. It’s such an ideal, perfect place to read poetry and talk about ideas. It provokes something in you, it opens you up. And then you hear the Kokosing farewell and you’re just like, “Wow, that’s really getting to me.” And nostalgia is just kind of baked into the place, like it’s even in that song. You know, the “farewell.” They invite you there, you fall in love with it, and then they tell you you got to leave.

There’s sadness built into the place. But that’s also the beauty. There’s a beautiful quote that I came across that says — Valerie Kaur said it — “Joy is the gift of love and grief is the cost of love.” So I feel like there’s a lot of joy in being a member of that Kenyon thing, but there is also grief involved somehow — that it doesn’t stick around forever or you can only catch it in glimpses. I think that’s what burned in me when I was thinking about it.

You know, it’s not a movie about college. It’s a movie about not being in college in a weird way. And loving college and then having to forge a life for yourself away from that.

When I got to grad school I was like, “Wow, I could really use a meal plan.” I missed going to Pierce or Gund, and having communal meals. Up until I was in my 30s, I was like, “I don’t like foraging for food by myself, I want to have a meal plan where I can see my friends.”

So there were certain things I just had a hard time shaking from college.

I was with two high school friends last summer or two summers ago, rather. And we were just having a great time, three of us. And I asked them — this is a very mean question to ask — but I asked, “What’s your favorite thing about getting older?” And my friend CH said, “I love the stuff I know, that I didn’t get from a book and that no one’s told me. the experience taught me.” He said, “I guess you call that wisdom, you know, the stuff that you only acquire by living through.” And I think that’s what Liberal Arts is. I hope it has some wisdom in it. I don’t want it to be an intellectual exercise. I hope there is wisdom born of experience, that’s what I was going for.

FRED AND FLANNERY: Do you miss college?

JOSH:

I mean, so much. I was there pre-cellphone, remember? I joke with people now, like, how did we even find each other? How did we know where to go?

I miss the happy accidents of running into people when you’re just wandering and it changes the whole course of your night.

I think there’s something so sacred about meals. And to be able to sit down at a large table with a group of people and share a meal and talk about your day. Loneliness was never a thing that hit me at Kenyon. I always felt surrounded by people. I miss the excitement of being on stage at the Bolton or the Hill. Acting was so pure at that point for me. I mean I still really love it and I feel much better at it as the years go on, but there was something about… I remember doing rumors by Neil Simon — Harlene directed — and also The Importance of Being Earnest, and it was just pure fun. It was just, like, hilarious. And it was just the greatest adrenaline rush. I miss all that.

I miss the weird psychedelic experience of walking to breakfast after an all nighter to get a paper and watching the sun come up. Like being so whacked out of your gourd. All that had its own kind of kick.

Yeah, I miss sitting in classes. Man, I would be such a good college student now. Like I really know how to read and engage with text. Maybe some of it’s wasted on the young but I think I got a lot out of it. I mean, I showed up and I was ready to be there. I don’t think everyone is ready for college. But I was.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.