Fighting the Good Fight

Two Collegian Magazine writers track the origins, and development, of radical organizations at Kenyon.

When the Kenyon Student Worker Organizing Committee (K-SWOC) was formed in April 2020, they entered into a long tradition of left-leaning organizing at Kenyon. Student life at the College has always gravitated towards academics, with a heavy emphasis on the humanities. But politics infiltrated the Kenyon bubble– the removed sanctuary of a liberal arts campus– many decades ago, and has shaped the history of the school ever since. These new organizers are not the first to pass through Kenyon, and push the limits of the school and outside world with varying degrees of success.

In 1968, the Columbia University anti-racist, anti-Vietnam War student protests captured the attention of the world. The history of student protest, particularly in the era of the late 1960s and early 70s, is often romanticized. However, the reality of the battle between students and authorities was often dark. In 1970, student protests on two college campuses were cut short by deadly police violence. At Kent State, one of our academic neighbors in Ohio, four students were killed. Ten days later at Jackson State, a historically Black university in Mississippi, one student and one local teenager didn’t survive a deadly police shooting. At around the same time, a 22-year-old Kenyon dropout and Weather Underground member named Terry Robbins was constructing a bomb with four of his peers, unaware that it would end his life. We have sought to build a timeline of Kenyon’s path through these turbulent moments in history, from the 1960s until today, told through the lens of the student movements and organizations unique to each period. This chronology is complete with our own investigation into each group, student attitudes about how they operated, the College’s reactions, and the larger political context as it evolved over time.

Young People’s Socialist League (1950's)

“The sunny hills of Gambier have of late been shocked from their dreamy complacency,” wrote R. S. Henes, a member of Kenyon’s chapter of the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL) on May 16, 1958.

Prior to the flurry of organizing in the late 50s and throughout the 60s, the word “complacency” was used frequently to describe the political culture of Kenyon. YPSL was one of the first to take a powerful stance against student apathy, and create a bridge between the Kenyon “bubble” and the turbulent outside world. The national organization formed as the official youth auxiliary of the Socialist Party of the U.S.A., centering student involvement as a necessary force against authoritarianism and economic injustice. Despite the official chapter being formed in 1948, Kenyon’s members grew increasingly active in the late 50s as political tensions heightened here and abroad. As YPSL member R.S Henes wrote in the Kenyon Collegian in 1958, they were dedicated to the values of democratic socialism, and a solution to, “present conditions of war, poverty amidst plenty, and oppression to a world of peace, prosperity, and positive freedom and opportunity for all.” Despite its national importance, Kenyon students outside of the YPSL found its shifts of political culture and critiques of administrative control at Kenyon to be disruptive and unwelcome. One Letter to the Editor in the Collegian described the YPSL as having a “sterility of originality and rational thought,” even describing the group as “nauseous.”

YPSL at Kenyon focused on shifting the political culture at Kenyon, with sponsored debates, lectures, Socialist guest speakers, and the occasional scathing criticism of the Kenyon administration. In 1959, they accused the administration of censorship after not being provided equal resources to print their ideas and organize, and were issued a dismissive letter in response by the Office of the Dean of Students: "I was not even interested in reading your material, let alone censor it." The YPSL accused the administration of violating “fundamental principles of democracy and liberty.” Therefore, the YPSL aimed at not just addressing the political apathy of the student body, but of the administration as well.

Student Social Action Committee (1960's)

As the flurry of political activity in the 60s intensified, so did Kenyon’s, not just through chapters of national organizations, but also through new Kenyon action committees dedicated to lending student support to boycotts, D.C. protests, and more. In 1963, Kenyon’s Student Social Action Committee (SSAC) joined a four-month boycott led by the NAACP against businesses and restaurants with discriminatory hiring practices and segregationist policies. In its beginning, the SSAC was unattached to any singular political movement. According to their constitution, they aimed to “aid the rectification of injustices occurring to individuals throughout the world” through nonviolent means of resistance.

Opposition described SSAC members as “rabid,” and their efforts as merely “a nice outlet for your consciences before you go crawling back into your warm beds in Gambier.” Still, the SSAC lended its support to actions against segregation started by pre-existing organizations such as the NAACP, both locally and nationally. In 1963, delegates from Kenyon headed to New York to present a petition to the national offices of segregated businesses in Mount Vernon. Frederick Houghton ’63 wrote an op-ed in the Collegian asking for broader support from the College to meet the Committee’s demands, namely ending racist hiring practices, integrating restrooms and water fountains, and equal service. Houghton wrote, “to add to the effectiveness of the boycott, an appeal has been made for students throughout the country to bring more pressure upon those national chain stores included in the boycott.” Houghton’s op-ed furthered the SSAC’s commitment to youth assuming a particular role and identity in social change, and a desperate responsibility to engage the entire Kenyon community in their organizing.

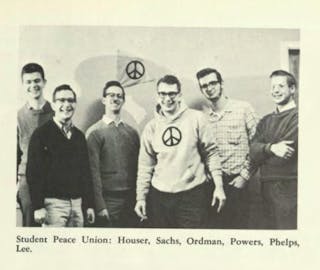

Student Peace Union and Kenyon Committee to End the War in Vietnam (1960s)

Members of the Student Peace Union in 1963. | COURTESY OF THE KENYON REVEILLE

In March of 1962, 8,000 students marched in Washington D.C. against American-instigated violence in the Cold War, particularly in Vietnam. Among the sponsors of the march were peace organizations such as Turn Toward Peace, as well as labor unions such as the International Electricians Union and the United Auto Workers. Six Kenyon students Student Peace Union (SPU) marched alongside the demonstrators, who, cutting their classes, drove through the winter snow from Gambier to D.C. to show their support at the White House. The SPU was a national union of students formed in 1959 which, as Kenyon students put it, was committed to ending the, “inadequate, self-defeating and profoundly dangerous” response to the Soviet Union, such as through imperialistic proxy wars and the rise of nuclear weapons. Much like the YPSL, it took the form of a web of small semi-independent chapters in cities and at colleges and universities that worked together to organize students nationally.

To further student participation in national events in cities like D.C., New York, and San Francisco, the Kenyon Committee to End the War in Vietnam (KCEWVN) launched with similar objectives to the SPU. In 1967, another group of Kenyon students and professors took a bus to D.C. to protest at the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Pentagon against the Johnson administration’s violent intervention in Vietnam. Students travelled throughout the country to take part in massive demonstrations, and spread anti-war pamphlets in the local Kenyon community. In one event, eleven students picketed Main Street in Mount Vernon, handing out anti-war literature to those who walked by. The SPU and the KCEWVN acted as both cultural and physical bridge between Kenyon and the most pressing national crises and demonstrations.

In the 60s, through the SPU and KCEWVN, the aims of Kenyon political activism began to focus on American militarization. Despite the shift in focus from the broader demands of the SSAC, the College student body and administration utilized similar rhetoric in their criticisms of the organization as with earlier groups. One Collegian op-ed titled “Aiding the Reds,” noted, “It cannot be denied that these objectives are good; however they will never materialize and in the end will be detrimental to our country.” Resistance to Kenyon’s SPU embodied American “Red Scare” fears, as opponents cultivated an imaginary alliance between Kenyon students and the Soviet Union. During this time, an opposing conservative group, the Young Americans for Freedom, began posting notices warning the Kenyon student body of countries “overrun by Communism.” But, despite the national organization’s disintegration in 1964, the SPU at Kenyon embodied a growing sense of resistance to the Cold War, and U.S. imperialism in general. As glaring as the opposition was, anti-war students forced into the political discussion at Kenyon a critical examination of American violence abroad.

Students For A Democratic Society (1960's-70's)

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) is one of the most well-known anti-war organizations of the late 60’s and early 70’s, so famous that it was included on a CIA watchlist of organizations partaking in anti-Vietnam War activities. In February 1965, Terry Robbins, who would later go on to join the Weather Underground, formed a Gambier chapter. Members saw themselves as a vanguard for fostering political action at Kenyon, a link between the “problems of the world” and the “academic walls of Gambier village,” as one member stated. Kenyon’s opposition to the SDS was especially focused on disruption to the college’s social fabric. One Collegian editorial, though welcoming the new SDS publication Vanguard, said they profoundly hope that “the SDS boys aren’t bent on transmuting the Kenyon student after the model of those alarmed Antioch types who, when blue about the state of things in Vietnam, proceed directly to the state capitol.” As the SDS hammered away at political neutrality, fear of Kenyon students seriously engaging in direct action developed.

Robbins never graduated from Kenyon. After on-campus organizing began to feel futile, he left Gambier and committed himself entirely to SDS. Soon, SDS would also become too moderate for Robbins, one of the first “Weathermen” and member of its offshoot, the Weather Underground Organization. In March 1970, Terry Robbins, Diana Oughton, Ted Gold, Kathy Boudin, and Cathlyn Wilkerson moved into an upscale townhouse at 18 West 11th Street, Greenwich Village. The home belonged to Wilkerson’s father. The five Weather Underground members were building a bomb, which they planned to place at a dance for noncommissioned officers and their dates at Fort Dix in New Jersey. The bomb was intended to “bring the war home” by killing as many people as possible. Instead, it detonated prematurely, taking the entire townhouse and parts of the neighbouring houses with it on the morning of the targeted event. Boundin and Wilkerson survived, going underground for years. Ted Gold was killed by the collapsing structure of the house. Oughton and Robbins died in the basement, where the bomb exploded. After this disturbing incident, student activists everywhere were forced to confront their motives and limitations, to reexamine their methods, and ask what got them to where they were.

For Kenyon students like Robbins, the specter of the draft made the horror unfolding overseas (and very visibly on television) all the more urgent and intense. The disaster of the Vietnam War, and America’s overreach into Cambodia, was a powerful force among millions of students in the U.S. Many of them would join SDS, or similar anti-war groups, to organize or at least attend protests. Sometimes they faced police violence, but generally, the young adults of the anti-war movement were peaceful, even as anger fueled them. Only a handful would resort to extreme methods, like cutting all social and financial ties in order to participate in the Weather Underground’s risky, morally grey operations.

Active Students Helping the Earth Survive (1990's)

ASHES (Active Students Helping the Earth Survive), struck a chord as the first radical Kenyon organization since the advent of SDS in the 1960s and 70s. The club’s newspaper appearances emphasize two threads in its early history: its environmental activism, and the most radical action of its brief first life. In 1991, in the dead of night, each ASHES member pulled a different fire alarm on campus. Understandably, the school was furious. Most Collegian coverage of the incident wasn’t kind to the perpetrators (one letter to the editor called them ineffective “seekers of self-satisfaction”), but the Kenyon “Alarmists,” as they were called, wanted to create a discourse. The stunt was meant to draw attention to U.S. intervention in Iraq, specifically the shock and fear of being woken up to bomb warnings late at night. The obvious “Bring the war home” element notably reflects the mindset of the 1960s and 70s student activists, on and off Kenyon’s campus.

Venezuelan opposition leader and Kenyon alumnus Leopoldo López ’93 H’07 founded ASHES, led the fire alarm action, and spearheaded the group’s most active and radical period. In May 2021, the Alumni and Parent Engagement and Annual Giving Office and the Center for the Study of American Democracy hosted a conversation with López, who reflected on the experience after decades of following a successful, but often dangerous, political career. López told a Zoom audience of Kenyon students and faculty that after being caught for the fire alarm demonstration in 1991, the perpetrators were suspended.

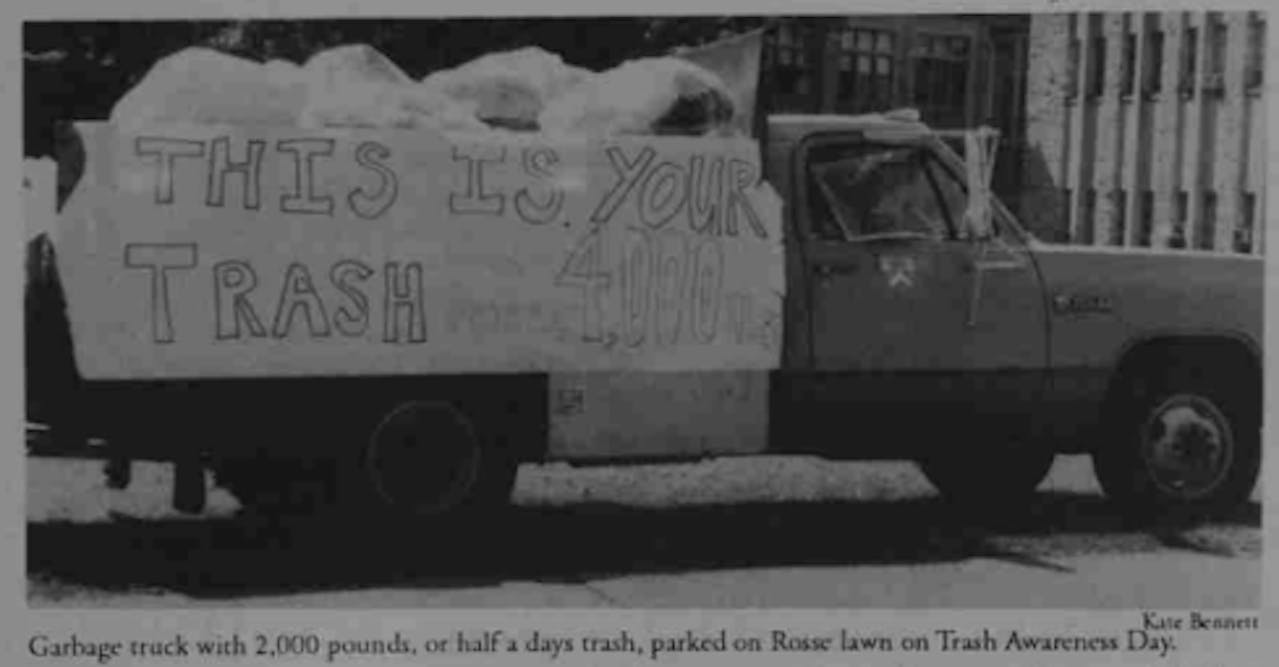

ASHES was slightly ahead of its time in terms of environmental activism. In April 1999, the student group hosted Kenyon’s Earth Week, lending its weight to a series of events much more palatable than the riskier anti-war action in 1991. A 1999 Collegian article even referred to ASHES as “Kenyon’s environmental activist group,” noting the organization’s focus on recycling, highway clean-ups, and even spreading awareness about climate issues to Knox County youth. As the organization’s focus shifted to recycling and compost, rather than the action-oriented philosophy it founded on, its influence faded and its presence gradually fizzled out.

An ASHES earth week campaign from the 1990s. | COURTESY OF KENYON COLLEGIAN

In fall 2019, ASHES returned under the leadership of Graham Ball ’21 and Helen Cunningham ’20. In November 2019, ASHES organized a protest outside the Morrow County Jail, less than an hour from Kenyon. The group of Kenyon students picketed the facility, demanding an immediate end to the jail’s contract with ICE, for which they were holding a number of detainees awaiting probable deportation. ASHES has also hosted speakers, and prior to the pandemic, held regular meetings on campus.

Ball said in an interview that when Leopoldo López spoke at Cunningham’s seminar at Kenyon’s Center for the Study of American Democracy in 2019, the College was a fairly apathetic place. ASHES, he believes, has played a role in changing the climate over the past few years, something he’s proud of. While Ball and Cunningham were still the only ASHES members, Ball collected information on ASHES from the Collegian archives, which contains records of their old exploits. The fire alarm action and its coverage, in particular, caught his interest. They didn’t try to copy the original structure of ASHES exactly, or mimic what used to exist, but they did try to rebuild with the old “spirit” intact. The core philosophy revolves around taking action: “Don’t talk about something if you can’t do anything about it,” said Ball, describing the thinking around redeveloping ASHES. “Everything has to be planned towards an action.”

Kenyon Young Democratic Socialists Of America (Present)

Democratic socialism and socialism have become strong political currents among American young adults in recent years, catching the interest of a generation disillusioned with capitalism by the 2008 recession. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), with its hundreds of local chapters and working groups, became a popular center of operations. At Kenyon, a chapter of Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) has taken root.

Kenyon’s chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America (KYDSA) began in 2017, with Lucy Irwin ’20, Patrick Conley ’20, and Chris Sheets ’20. According to Irwin, the group wanted to build “a political club with a more open, encouragingly egalitarian structure,” using the momentum of DSA in the aftermath of Bernie Sanders’ first campaign for president.

In an email interview, KYDSA social media chair Henry Haley Goldman ’23 said that KYDSA has grown a lot in recent years. “I think we have been seen in a more positive light recently,” he said. “We were able to connect with ECO and co-host lectures this semester, as well as connecting with Students for Justice in Palestine in previous semesters.”

Kenyon Student Workers Organizing Committee (Present)

In 2020, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic that upended the world, student workers found themselves especially challenged. Kenyon students responded to job instability for students on work-study, along with an array of other issues that couldn’t be resolved otherwise, by forming the Kenyon Student Workers Organizing Committee (K-SWOC). The organization is as much a community for students with on-campus employment as it is a vehicle for negotiating power with the College. The formation of K-SWOC, which would be the nation’s first all-inclusive undergraduate student workers’ union if recognized, has opened questions about the role of student workers, the relationship between students and administrators, and the importance of income from on-campus jobs. As of May 2021, K-SWOC still has not been recognized by the Kenyon administration. But grassroots organizing and mutual aid efforts surrounding the union and its goals have continued at Kenyon, undeterred.

Sights from a K-SWOC rally. | Photo by John Ortiz

This comes not only in the context of a pandemic, and of Kenyon’s radical history, but at the outset of a third consecutive year of an upswing in global protest movements. Since 2019, organized resistance, mostly nonviolent, has been in the air worldwide. Last summer, it came to the U.S. in its most concise and unyielding form yet: months of nonstop peaceful protests in response to the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black Americans. Before that, Kenyon students participated in school walkouts for gun reform, or “strikes” for climate justice.

As the politics of our era continue to develop, it is vividly clear how today’s movements, and their opposition, are informed by the past. The legacy of political activism at Kenyon can’t be bottled into a singular focus or strategy. But over the decades, students have emphasized the critical role of each new generation in radical social change — both nationally and on the Hill. Leftist values and radical politics have long thrived at Kenyon, and the impact of the past is still visible today. From the civil rights petitioning of the SSAC to K-SWOC’s persistence despite administrative opposition, all of these organizations, even through their vastly different political contexts and successes, were guided by a commitment to penetrating a culture of collegiate political apathy and neutrality. When asked how he thinks people on campus view ASHES today, Ball paused, and admitted some people at Kenyon probably aren’t fans. But, ultimately, he said: “I would like to think that people see us as fighting the good fight.”