Glenn McNair on Police Violence

Before joining Kenyon’s Department of History in 2001, Dr. Glenn McNair spent 12 years in law enforcement. He served five years as an officer in Savannah, Ga. and seven years working for the Treasury Department in the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. As an academic, McNair has investigated the contentious relationship between African Americans and the American criminal justice system. In conversation with The Collegian Magazine, McNair spoke about his decision to switch careers, the similarities between the two professions and his memorable first day as a police officer.

What made you decide to make the career switch between being a police officer and being an academic?

I decided to make the change because a part of me had always been an intellectual. There’s a just a part of me that was very intellectually curious and, frankly, most criminals are not James Bond-style villains, so after a while [the work] was starting to get predictable. The action and adventure was still going on, but I found myself lacking a kind of intellectual stimulation. I had done pretty much every type of investigation I could think of and I thought, “Well, you’re still in your early thirties, are you going to do another 20 years of this?”

What were your duties in law enforcement?

Traffic accidents and domestic disputes, and bank robberies, and shoplifting, you name it. I took part in a bombing investigation in 1989. A man had planted bombs through the mail to federal judges in the Southeast—that was the biggest bombing case. But most of the time was spent [working on] drug dealers with guns. This was right at the beginning of the war on drugs, so I spent most of my time investigating crack gangs and meth gangs.

In your book, Criminal Justice, you talk about being stopped at gunpoint by other police officers on multiple occasions. How did these moments influence your work, your views of the criminal justice system and now your research?

Probably not as much as it would affect someone who didn’t have a background in law enforcement. Police officers have, what I call, a variety of tapes in their heads that they put in when they come in contact with different groups of citizens. And the tape that is playing dictates how they’re going to interact. There’s the tape of the white suburban housewife and her kids— the “protect and serve” tape that says the odds of this being a dangerous or a negative interaction are pretty low. The black tape is a different tape. It’s one that says, this encounter, no matter who the person is, can potentially turn deadly in seconds and I have to be ready to kill them.

If you’re black, and it doesn’t matter what your class level is, you have had encounters with the police where they are treating you like a suspect, often in your own home, ready to engage you violently. Each encounter I had with the police is always, in my head, “This can go really badly so you have to follow this step by step and respond in a way that neutralizes all of the fears they have in their heads before this goes wrong.” In terms of how it makes me feel as a citizen overall, it’s distressing.

This not a new problem. Going back to the country’s founding, law enforcement agencies were started with the goal of controlling black people, so this model of protect and serve was never at the forefront. So much of what police officers are responding to is this deeply ingrained cultural sense that black people are fundamentally dangerous. The problem with race in America is we’re all implicated in it. So the first time that any racial thing happens, everybody gets defensive for various reasons. Nobody wants to deal with systemic anything because when you talk about systemic stuff, everyone’s implicated and sacrifices have to be made. It comes down to, how much do you care about those people who are not you? That level of caring has never risen past a certain point. When black interests and white interests coincide, you get progress. The moment those things diverge, it’s back to business as usual.

If you were to go back to your criminal justice job now, how would you approach it differently considering the writing, research and teaching that you have done?

I don’t know that I would do very much differently. I was always a different sort of police officer. It’s a high stress job and what it demands of you is even greater because you have this power and authority over people. As a regular police officer on the street, you are one of the most powerful people in this society. You have the power to take away someone’s freedom and to take away their life and to do it on your own authority. The psychological screening that goes into choosing law enforcement people is not very good, so you have lots of people who are just not psychologically and emotionally equipped to be doing this.

Is there a moment that is most memorable from your law enforcement career?

Just my first day. My first day was this weird combination of experiences that I wasn’t quite prepared for. It was a day when I got into my very first fight with somebody, to be followed by a guy asleep on a porch. It turns out he wasn’t asleep. He was a Vietnam veteran who was having flashbacks to his time as an executioner in Vietnam and he hated my partner and liked me so I was the one who was in the rubber room with him while he was having flashbacks. Could it be any worse than this?

Yes, right after that there was a house fire with a dead body. There I was looking at a burnt corpse. In my first day, [I thought], “You’re definitely not going to be able to do this. This is just nuts of a job.” And then a funny thing happened. I went home. I went right to sleep. When I woke up the next day I was like, “Maybe there’s more to you than meets the eye.” I was pretty sure that [that first day] would have been completely unsettling, and yet, it wasn’t. I went to work the next day—it was a totally quiet day. We literally ate doughnuts and drove around. But that first day I’ll always remember. That first day is the one that stands out most vividly because it was a moment that I realized that there are things about yourself that you don’t know until they’re tested. That was a real revelation for me.

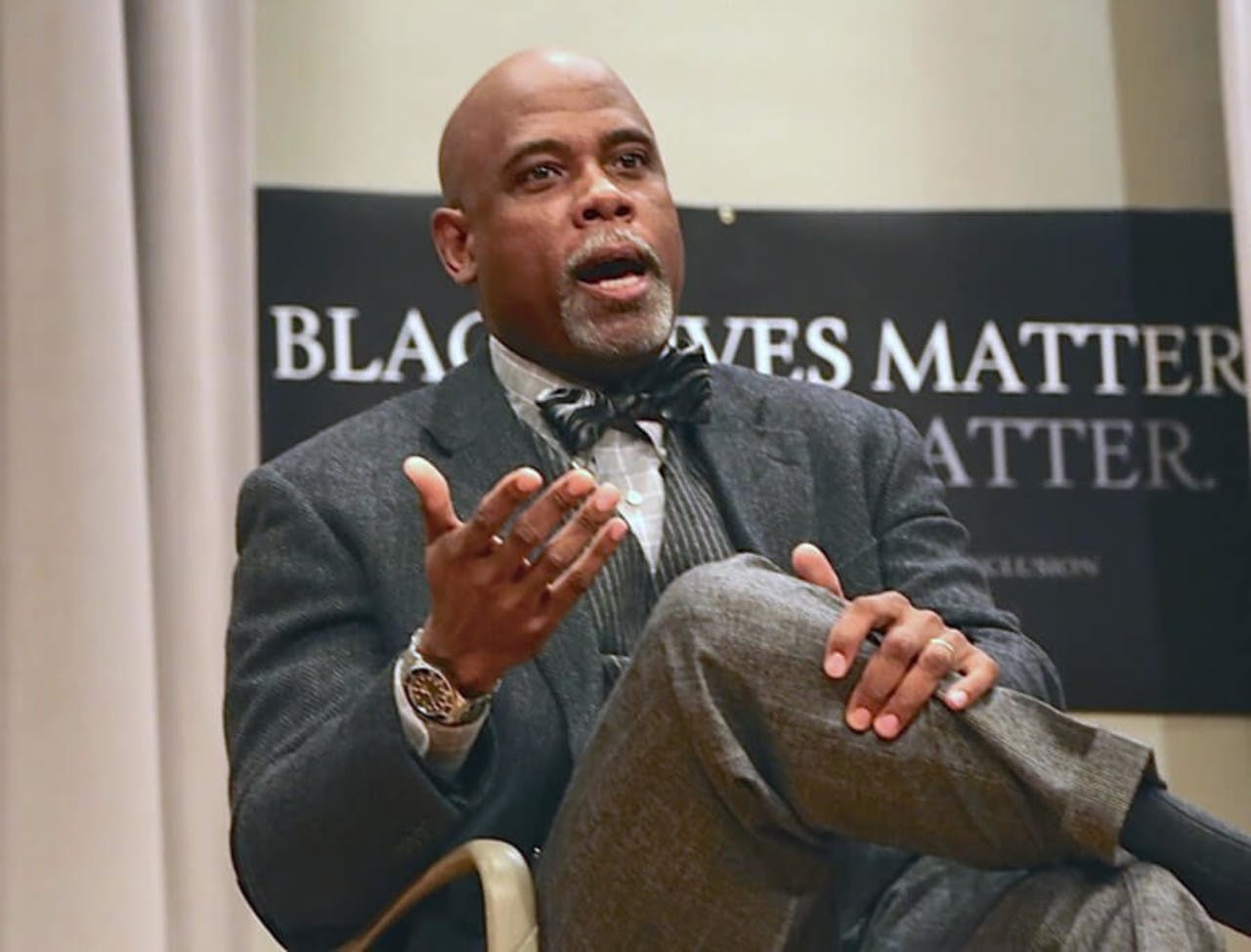

Professor of History Glenn McNair speaks at a Rosse Hall panel on “Black Lives Matter.” McNair previously served as a police officer for five years.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Kenyon CollegeWhose job is it to teach young black men how to interact with police?

Parents have been doing it forever … but in light of the most recent incidents, schools are starting to do it now. That’s what makes it so tragic: that parents, institutions, relatives and friends have to train their children how to interact with people who are there to protect them because those people might kill them. The tactics that [blacks] have to learn, those are temporary survival measures. I hope we get ourselves to a day when that is no longer the case, but as I said, I’m not optimistic about that in the short term.

What do you think of body cameras?

Most people think that there will be a panacea — that officers will become more self-aware and not engage in these inappropriate behaviors. I don’t think it’s going to work. When officers are involved in these shootings, they don’t think they’re doing anything wrong. In their heads, they are literally acting on a deadly threat. So it’s not, “Hmm, I hate that black guy. I think I’m going to kill him but this camera’s here so I’m not.” When [officers] shoot, that camera is not something they’re conscious of because [they] think they are doing what is right. In terms of cameras beings useful as evidence, absolutely. If it wasn’t for cell phone cameras and dash cameras, we wouldn’t be having this conversation now. It’s this culture that has to be changed. And the only way it’s going to be changed is if police officers are held accountable when they engage in these kinds of unlawful shootings. Either they go to jail or they’re fired, but it cannot be business as usual.