Kenyon's libraries: a vexed history

The College has never gotten the library it deserves.

Kenyon has a complicated relationship with its libraries. In June, the College will begin construction on its newest one, which is set to replace the Olin and Chalmers Memorial Library. This may come as a relief to some. College Historian and Keeper of Kenyoniana Thomas Stamp ’73 said that Olin always tops his students’ list of least-favorite buildings. In an opinion piece from the Nov. 3, 2016 issue of The Kenyon Collegian titled “Students deserve more input on new library,” Maya Lowenstein ’18 writes, “For a school consistently ranked as having one of America’s ‘prettiest college campuses,’ Kenyon’s trustees sure are self-conscious.” But a short look back reveals that frustration surrounding Kenyon’s various libraries has been a near constant in our history.

When Kenyon was founded in 1824, it did not have a library. Philander Chase, the College’s first president, was an ambitious book collector, and his home in Worthington, Ohio, served as a makeshift repository for the College’s books. After the College moved to Gambier, the collection received its own cabin.

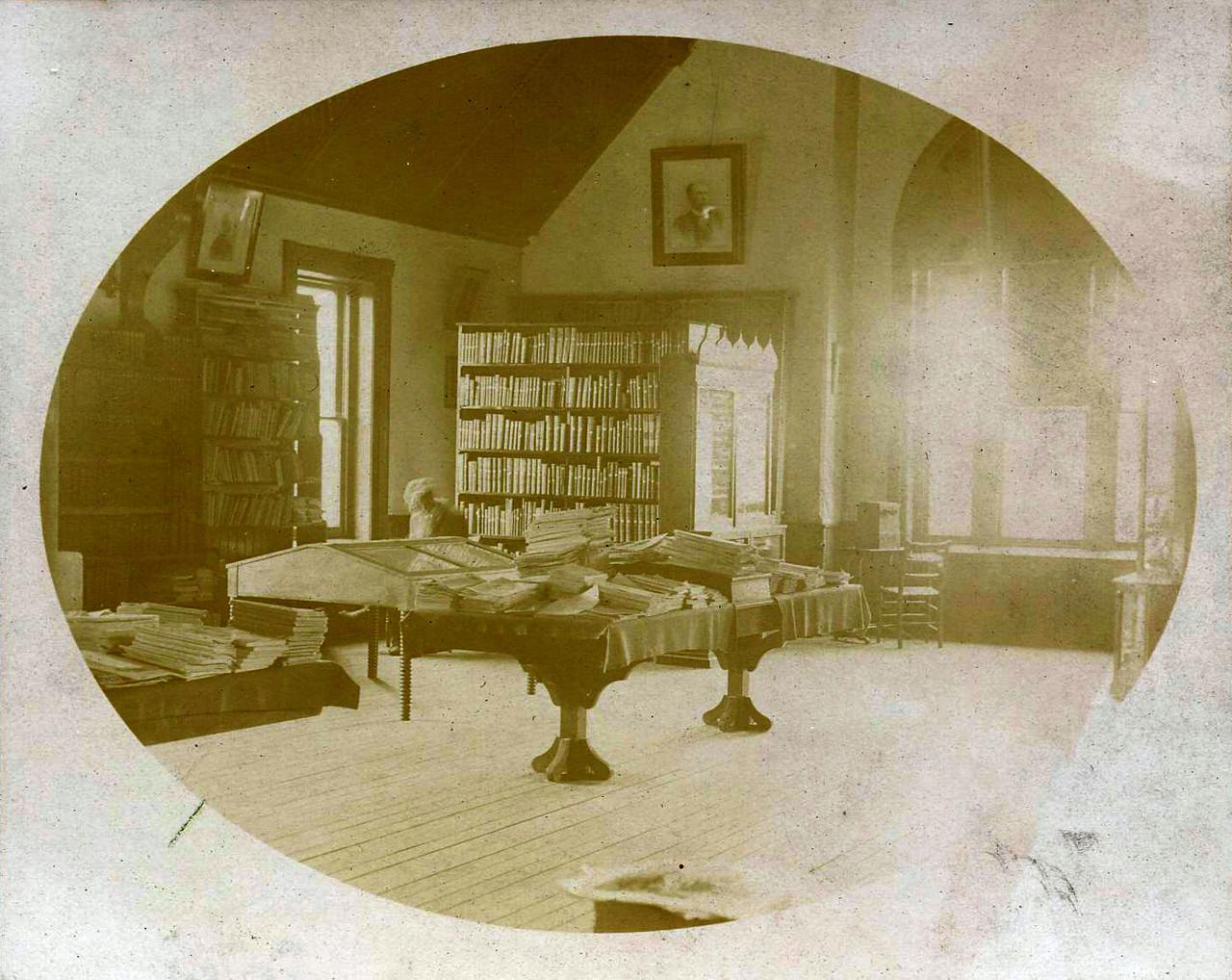

Kenyon built its first real library, Hubbard Hall, in 1887. Mary Hubbard Bliss, the president of the Columbus Art Association and the daughter of William Blackstone Hubbard, the founder of the First National Bank in Columbus, financed this new building. It was characterized by its large, sunlit study space.

Unfortunately, the school’s first true library would also prove to be its shortest-lived. Hubbard was not built with fireproof brick. It burned down New Year’s Day in 1910 and was replaced by the noticeably smaller Alumni Library, today called Ransom Hall.

Although the Alumni Library may have been cozy, Stamp told the Magazine it had the feeling “of being crammed in like sardines.”

“It’s not that they didn’t build what they needed at that time,” said Stamp, “The plans for expanding were meant to be later. Those would come to fruition as needed.”

How the College determined need is not obvious; within a decade, portions of the College’s collections had to be housed in small, barrack-like annexes.

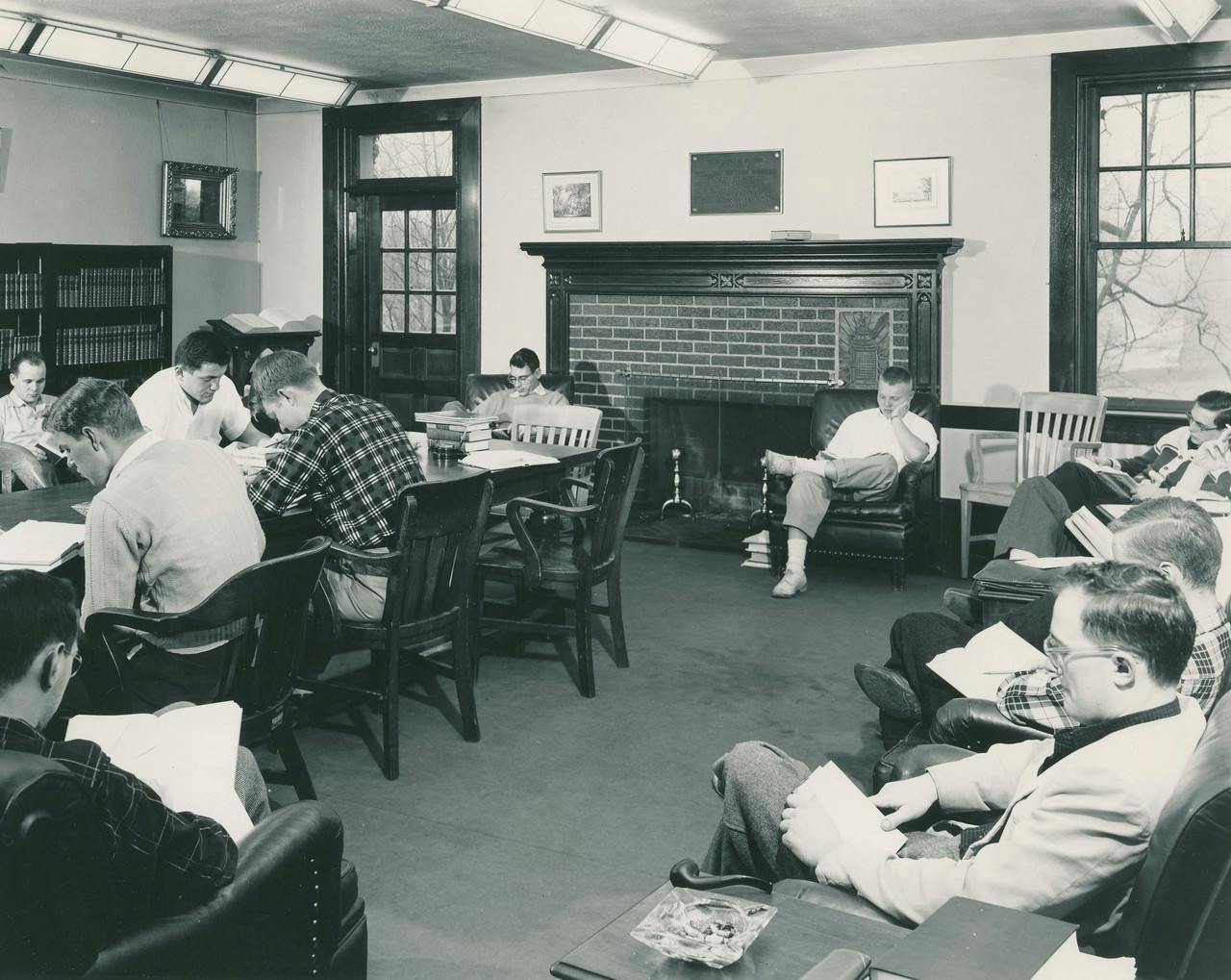

The Alumni Library was too small for the College’s needs. According to Tom Stamp, it was always "crammed like sardines."

When Gordon Keith Chalmers came to Kenyon as president in 1937, he aspired to make Kenyon the best college in the Midwest. This meant addressing the library problem.

By 1938, he had solicited plans for a replacement.

The architect, Alfred Morton Githens, designed a collegiate gothic box with a facade in the style of Peirce and Samuel Mather Halls, with towers, a grand arched entrance, and more square footage than the current Chalmers library.

“They were actually well on their way to actually constructing that building,” Stamp said. But Chalmers’ plans were disrupted by the rationing of building materials that came with World War II.

After the war, the G.I. Bill led to the influx of even more students, including Paul Newman ’49, and made the need for a new library increasingly dire. Chalmers tried again to pursue Githens’ plans. This time, a fire in 1949 consumed Old Kenyon, and the disaster directed would-be library funds to re-erecting Kenyon’s most famous building.

Chalmers died suddenly in 1956 at the age of 52, meaning his plans for Kenyon’s library would never come to fruition. His namesake, the Gordon Keith Chalmers Library, was completed in 1962.

Hubbard Hall, Kenyon’s first real library, was characterized by its large, sunlit space. It burned down in 1910.

On November 2, 1962, the Collegian documented how Chalmers’ friend, the poet Robert Frost, delivered a rather dry dedicatory to a crowd of mostly outsiders. Besides giving a lukewarm review of what would be Frost’s last public appearance, the issue of the Collegian also featured a variety of perspectives on the new building.

Roberta Chalmers, the widow of President Chalmers, described the building as “charming.”

A student op-ed described it as a “pretentious tomb.”

Also, sarcastically: a “cathedral of the ‘modern spirit.’”

Even so, Stamp said feelings toward the library were generally positive — at first.

The excitement surrounding Chalmers’ technological advancement and size soon wore off. The College continued to grow, particularly when it began enrolling women in 1969, and the increasing demands of technology in education further burdened the library.

By the mid-1980’s, Kenyon’s administrators had decided to revamp the building to add space and technology. In order to preserve the memorial to President Chalmers, the administrators and architects eventually decided to just build a new structure in front of it and connect the two.

The construction of Olin Library began in 1984. When its renderings were released, a student writer for the Collegian praised the glass atrium, calling it “reminiscent of the I.M. Pei structure which is soon to be built in the courtyard of the Louvre in Paris.” Olin Library, atrium and all, was completed in 1986. The Louvre Pyramid was completed in 1989.

Upon its completion, Olin added 54,000 square feet of space for books, studying, and technology. It also provided a change of scenery from Chalmers’ boxy front, which people had grown tired of.

It did not look like the Louvre. Stamp’s history mentions an administrator who said, “The best thing about Olin Library is that it’s in front of Chalmers Library.”

Over the years, Olin’s design, featuring oatmeal gray concrete aggregate that was cheaper than Chalmers’ stone exterior, became increasingly loathed. Equally dissatisfying were Olin’s functional shortcomings. Stamp attributes both of these traits to the postmodern architecture fad, in style at the time of the library’s construction in the mid-1980s.

The fad did not last very long.

For one thing, people did not like the lack of a central entrance, even though the entrances in the towers were supposed to be nods to collegiate gothic style. There were also complaints about the fact that the entrance to the circulation desk and the stacks was on the second floor, although this was a popular feature of library design at the time.

Other complaints concerned the fact that Olin cut off what was once a panoramic view of the campus from the Gates of Hell. After Olin was built, students could no longer see past it on the right side to Rosse Hall.

It was clear that Olin’s life would also be limited, as it, too, would soon fail to meet Kenyon’s high demands.

“The backlash against Olin built relatively slowly until it was a consensus that the building just didn’t work,” Stamp said.

Stamp himself began to notice this consensus around 15 years ago, when he first started teaching his class on American college architecture and heard about students’ dislike of Olin.

“There are always situations where buildings that our firm has designed in the past outlive their usefulness,” Robert Roche, the historian who manages the firm that designed Olin, wrote in an email.

Once again, Kenyon received the largest gift in the college’s history, this time to the tune of $75 million, with which Kenyon will pursue construction of a library equipped to handle its latest needs.

This new library will mark a break from the past. Where Olin and Chalmers both deviated from traditional design, the new library will create a degree of continuity and consistency with the campus, Stamp said.

He also pointed out how the library’s footprint is more accommodating to its surrounding buildings than Olin, with its harsh, jutted-out footprint. Called the Kenyon Commons, the new library will be “state-of-the-art,” according to the Kenyon website, and its technological capabilities will be a major boon for “21st century learning.”

We’ve come a long way since our log cabin days. ■