The Big Trip

How one weekend of drug use brought Kenyon into the 1960’s.

It was the weekend of Oct. 11, 1968, a weekend Scott Powell, class of ’70, describes as a “feel-good blur.” He wasn’t alone in this feeling: an estimate of three to four hundred students, having ingested the mescaline derivative MDA, littered Kenyon’s Middle Path. They rolled in the grass, scurried into the high branches of trees and embraced, all while declaring their undying love for God, the universe and each other. That weekend, then-Dean of Students Tom Edwards was hosting an alumni dinner. Powell remembers seeing one of the diners, an alumnus from the 50s, walk up to Edwards as he watched the students frolick. “Tom,” said the alumnus, observing the scene, “what the fuck is going on here?”

This is one of many versions of this story. In another version, Edwards himself is asking this question to the Kenyon soccer team, many of whom were tripping themselves. Other tellings include then-President Bill Caples. Whichever version is the real story, that question — what the fuck was going on — has yet to be answered. While “MDA weekend,” as it came to be known, lives on as urban legend, tangled up in mythology and hearsay, what it meant for Kenyon at large remains a mystery. Was it a watershed moment, or a bit of harmless fun? A mass consciousness-raising, or a gaggle of frat boys playing hippie? Throughout most of the turbulent 1960s — a decade of racial reckoning, brutal imperial war in Southeast Asia and widespread youth rebellion — Kenyon remained, for the most part, a sheltered bastion of privilege. As the decade progressed, however, the cracks on the facade began to show. The story of MDA weekend is the story of an institution teetering on the edge of the future, one that acts as a microcosm for the powerful historical currents that ran through the late 1960’s.

MDA, or 3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine, is a close relative of MDMA, or ecstasy, and produces the same effect — euphoria, arousal and a feeling of deep emotional connection to those around you. MDA was first synthesized as part of the military’s search for a “truth drug” to aid with interrogations.

That search began in 1916, when doctor Robert House attended a home childbirth. The mother had been dosed with scopolamine, a substance often given to women in labor at the time and MDA’s close chemical cousin. Despite the immense pain the mother was in, she answered each of House’s questions clearly and coherently. House realized this was an effect of the scopolamine, and began testing out the drug in mock interrogations.

By the 1930s and 40s, MDA was used as a “truth drug” by the Nazis to aid in interrogations at Dachau and Auschwitz. “In single cases, the [prisoners] got furious,” wrote Dachau physician Dr. Kurt Plotner. “In other cases very gay or melancholic … The examining person in every case succeeded drawing even the most intimate secrets from the [inmates] when the questions were cleverly put.”

After the Second World War, MDA was employed by American psychiatric hospitals as part of a series of experimental therapies, with often devastating effects. In 1953, at the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI) a patient named Harold Blauer was admitted after complaints of severe depression. Blauer was put on a steady dosage of MDA, DMA and MDPEA. On Jan. 8, despite complaints of hallucinations and violent seizures at lower dosages, Blauer was injected with 450 mg of MDA, which proved to be fatal.

By the time MDA arrived on Kenyon’s campus, it had become one of the most popular street drugs in the country. The formula was passed around in “cookbooks” and developed in a network of underground labs. Usage peaked in the late 60s, right before the drug was scheduled by the Drugs Enforcement Administration in 1970. Despite its relative popularity at the time, MDA was a rare sight for the average college student, and many participating in the weekend had no knowledge of the drug or its effects.

Looking back, Powell is skeptical about the more profound aspects of the psychedelic experience. “I remember being 18 and thinking, ‘if I take acid, I will see God,’” Powell said. “Nope. Nope. I just saw a bunch of paisley on a wall.” Powell is now retired, and lives in Houston, Texas. As a first year, Powell intended to study Russian, but ended up a German major instead. He joined the Archons, which at the time was a registered fraternity with a reputation for encouraging all types of experimentation.

Founded by alumnus Henry J. Abraham ’48 as a social hub for older students returning from the Second World War, Kenyon’s Archon chapter sat askew from the rest of campus culture. No first years ever “rushed,” and by the 60s Archon was known as a safe place for gay and closeted students. Archons were long-haired, “artistic” and known to be regular smokers of cannabis and experimenters with psychedelics. When Powell was a first year, one of his “brothers,” an upperclassman, ran a peyote business based around a convenient loophole. Every month or so, Powell’s classmate would call a botanical company in Texas and place an order. So long as he signed a statement that the shipment was for botanical purposes only, he could count on a regular supply. As legend has it, it was two Archons who purchased the 400 doses of MDA that would throw Kenyon’s “culture war” into stark relief.

With every alumnus interviewed, the story of how the weekend came to be was about the same: Two Archons drove up to Michigan — either the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor or Michigan State — and bought hundreds of doses of MDA that had been synthesized by a group of graduate students. They purchased the MDA with the intention to sell, but once back on campus were so moved by the drug’s effects that they started to give away small amounts to close friends. These smaller group trips occurred with greater and greater frequency, until the Friday of Oct. 11, when a critical mass — at least one third of the campus population by most estimations — were tripping.

Word spread to other colleges in the state, spurring a small migration to Kenyon’s campus over the course of the weekend. The effects of the drug were incredibly visible: Students skipped classes, swim meets, and concerts. They carried extra doses of the drug in their pockets, passing them out in front of Peirce Dining Hall. Fearing a crackdown from federal authorities, President Caples made a speech on the steps of Rosse Hall unequivocally condemning the revelers, expelling two students and suspending several.

On Friday, Oct. 11, Peter Muller, ’70, was asleep in his Hanna double. Without warning, a classmate rushed into his room, sweating and half-naked. Recognizing Muller, this classmate said he was starving, and asked if Muller had any food. Muller offered a sandwich from his mini-refrigerator. “So he went in the refrigerator and got some food,” said Muller. “He was carrying a big mason jar full of little pink capsules. As a thank you for the food, he reached in the mason jar and pulled out a handful of these capsules, and dropped them on my desk.” Muller was sober, aside from the occasional beer on weekends, and had heard nothing of the drug or its spread. Walking out onto Middle Path, Muller encountered a close friend, the first sign that something was wrong. “He was all agitated and kind of twitchy and shaky,” said Muller. “He started telling me how this was the beginning of something that was totally going to change everything… that we’re going to shut off all the social structures and conventions, and we’re all going to start living nomadically and sharing property in common and loving each other… I felt like the only sane man on campus.”

Muller was not the only one to notice a utopian zeal in those who had taken the drug. Richard Brean ’70 was returning from a trip to visit his mother in Pittsburgh when he was approached by an acquaintance outside of the Hill Theater. “I mean, he comes over just staggering towards us,” said Brean. “And I thought he was drunk, you know, which was not uncommon at Kenyon.” The man grabbed Brean’s face and stared into his eyes. “He looks at me like we’ve been together since creation,” said Brean, “and we’re gonna be together until Nirvana.”

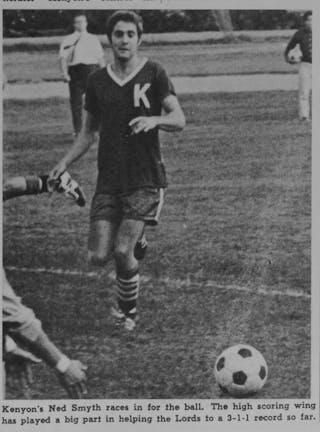

Many who took the drug developed a powerful sense of empathy that proved to be disruptive to the day-to-day operations of the College. Ned Smyth ’70 was the captain of the soccer team. While at Kenyon, Smyth and several of his teammates experimented with marijuana. Smyth remembers smoking with fellow soccer players in the stairwell of Old Kenyon. “When you first do it, you just giggle, and we would be giggling, and the echo would make us giggle more,” Smyth said. “And all these people would come in, and they’d go, ‘What’s wrong?’” On MDA weekend, the team had a home game against Marietta College. Several players, along with a large portion of the audience, had taken the drug. “One of [my teammates] ran into the goalie, knocked him down,” Smyth said. “He didn’t do it maliciously, but by chance the goalie fell down. This guy is on his hands and knees going, ‘Are you okay? Can I help you?’ I’m yelling at him, ‘Get up! shoot the ball!’ We could have got a goal.” The Lords won that game 5-0.

Smyth on the field as the captain of the Lords soccer team. A portion of the team had taken a dose of MDA prior to taking the field. | COURTESY OF KENYON COLLEGIAN

Once word of the weekend began to travel, first to the neighboring Mount Vernon and then across the county, Kenyon’s administration went into a panic. The late 60s were one of the most financially difficult periods in Kenyon’s history, and the school was in danger of closing. In order to save their endowment, the College had announced the opening of a women’s coordinate college, joining a rash of liberal arts colleges who had embraced coeducation while also lining their empty pockets with a new cache of tuition money. If the parents of the first class of women heard that their daughters’ peers had participated in a mass dosing of psychedelics, the College feared that a critical mass of enrollees would withdraw.

At a faculty meeting the following Monday, Edwards flirted with the possibility of bringing law enforcement to campus. “The use of drugs had gotten completely out of hand during the latter part of the preceding week,” read the meeting minutes. “The administration proposes to get to the source of the supply if possible and realizes the police may have to be called in to accomplish this. If the larger community surrounding Kenyon becomes aroused over this problem, outside authorities may be called in whether we like it or not. We may very well have a legal obligation to inform the Federal Government and that the college may be deemed an accessory if it did not.”

While there is no credible source that has confirmed the presence of the FBI, rumors of the agency’s involvement circulated widely. Smyth remembers traveling with his teammates to an away game when their bus was suddenly pulled over. “These guys came on, and called out two names and took them off the bus,” Smyth said. “That’s the last I saw of them. And it wasn’t people from the administration. As I remember, it was people we didn’t know.” Years later, Smyth ran into a classmate who told him that he had seen one of the students who was pulled off the bus begging on the street in Pittsburgh, dressed as a Hare Krishna.

Regardless of the FBI’s involvement, Dean Edwards’ search for those who had distributed the drug was paranoid and relentless. Muller remembers being approached by a fellow Archon, who told him that he had been pinned as a dealer who had helped to provoke the debacle. While Muller barely drank alcohol, he wore his hair past his shoulders and played in one of the school’s resident rock bands, St. John’s Wood. “Because of his appearance Edwards thought he was a giant spider sitting in the middle of a web, with all his children running around delivering drugs to innocent young Beta Theta Pis,” said Powell.

The Thursday after MDA weekend, President Caples addressed the student body on the steps of Rosse Hall. He broadly condemned the actions of students who had partaken. “No one has any right or license to conduct himself as to destroy the good work or name of others or the community,” Caples said. “Yet here people have assumed it.” At the end of his speech, Caples uttered a phrase that would follow him until his resignation: “Like it or not, the law establishes the morality or immorality of any act.”

“The philosophy department grabbed their chest and died when they heard that,” said Powell.

The student body president at the time, David Hoster ’70 had some harsh words for President Caples at the Student Council meeting the next week. He called speech “dangerously extreme,” taking particular issue with the president’s equation of morality and legality and claiming that his statements were antithetical to a liberal arts education. “Like it or not there are no standards anywhere, and that includes the law, that are so perfect that they are beyond question or exclude violation out of hand,” Hoster said, “and one who asserts that law is an absolute unto itself and in the same breath says there are no easy or final answers has involved himself in a massive contradiction.”

Now a retired episcopal priest in Georgetown, Texas, Hoster believes that Caples’ speech at Rosse Hall permanently damaged the president’s reputation. “His reaction to the MDA weekend was definitive in terms of how he was perceived by the students. There was a honeymoon before that, but after that, the honeymoon was over.” By speaking out against Caples, Hoster hoped to assert the agency of the student body. “I was trying to say, ‘You’ve got students you have to deal with here too,’” Hoster said. “And yes, they do have a mind of their own, and they’re not going to accept your absolute view of legal and illegal as the final word on things.” Brean believes that Caples’ statement about the absolute authority of the law was particularly tasteless given the political turbulence of the time. “People getting arrested for protesting against the draft, well, that’s a law too,” said Brean. “And so was segregation in the South. That was the law. You didn’t have to be a genius to think, ‘What’s Caples saying?’”

“Like it or not” quickly became shorthand for students’ dissatisfaction with Kenyon’s administration. Smyth, who was a studio art major at the time, screen printed hundreds of shirts with a design in which the phrase twisted into the shape of a screw. The shirts were immensely popular, reaching as far as Denison College. “You’d walk around Granville and you’d see these shirts, you know,” said Brean, “’Like it or not.”

Brean, who worked as a lawyer for the United Steelworkers in Pittsburgh before his retirement, credits Caples’ shrewd dismissal of students to his experiences negotiating with unions as an executive at Inland Steel. “He was used to people with real grievances,” said Brean. “And frankly, a lot of what we did was posturing. But part of it was that we felt, intensely, that a new world was coming.”

Kenyon in the 1960s was a world of tradition. Fraternities ruled the social scene, and those who refused to join an organization were often treated as outcasts. While there had been flare-ups of political activity, compared to Columbia or University of California, Berkeley, Kenyon students were overwhelmingly moderate. While several alumni who were interviewed see MDA weekend as a cultural blip that faded as quickly as it arrived, many remembered that the mass trip and Caples’ clumsy response helped to unify students across social divides. Brean grew up in a working-class, Jewish household. He remembers a noticeable disconnect between lower- and higher-income students. “Kenyon used to be split between a lot of very smart public school people and then the bottom quarter of lots and lots of private schools, boarding schools. They were smart guys who slacked off all through high school,” said Brean. “They thought they were more elite than the rest of the folks.”

However, after Caples’ speech, there seemed to be a mutual understanding that the administration had made a misstep. In addition, the shared experience of tripping had forged connections between fraternities, as well as leading to fractures within fraternities that led their members to feel more comfortable stepping outside their social boundaries. “Too many people had tried the drug, which meant usage included students from many of the fraternities,” wrote alumnus Douglas Holbrook ’72. “This meant there were now divisions of attitudes within the fraternities. If you had taken MDA, then you were likely to try smoking pot. And if you wanted to smoke with someone, you might have to go and hang with someone outside your fraternity.”

Drug use was not as easy an avenue to social cohesion for some students, however. Ulysses Bernard Hammond ’73, a founding member of Kenyon’s Black Student Union, remembers that the few Black students enrolled at the College felt an immense amount of pressure to be exemplary students that led them to avoid the more hedonistic aspects of Kenyon’s counterculture. “By this time, alcohol and drugs were becoming a solid part of student culture, but not as much of the Black student culture,” said Hammond. “That’s not to say there wasn’t experimentation, but we realized that we represented more than just ourselves. To many, we represented all Black people.” The ability to participate in such a visible act of transgression was in many ways the domain of those who were certain that they would not face any serious consequences.

1968 was a momentous year for world history. Backing away from promises to de-escalate the Vietnam War, the U.S. military launched the Tet Offensive, leading to 45,000 casualties. Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated, leading to uprisings in cities across the country. Abroad, the Prague Spring threatened Soviet authority in the Czech Republic while demonstrations in Paris led president Charles De Gaulle to step down. That summer saw a massive outbreak of police violence against Black Americans. Mass arrests and beatings followed student-led demonstrations at the Chicago Democratic Convention (DNC), where Hubert Humphrey was chosen as the nominee to run in the general election against presidential hopeful Richard Nixon. While Kenyon was certainly not the nexus of student activism, smoke from the fires that had been lit across the country would occasionally waft through campus.

Rather than viewing MDA weekend as the main catalyst for Kenyon’s cultural shift in the late 60s, Holbrook sees the weekend as one part of a larger continuum of change, one that was propelled by a series of crises in the United States. “There would later be other challenges to authority or the status quo,” Holbrook said. “This would be especially true once the women arrived.”

On Sept. 28, two and a half weeks before MDA weekend, Morris Liebman, a Chicago lawyer, prominent figure at the DNC and avid supporter of presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey, delivered a lecture to Kenyon students on the future of the Democratic party. Liebman expressed anxiety about the burgeoning youth-led “New Left” movement. “The most threatening thing we have [in politics] today is continued complexity,” said Liebman. “That people are trying to solve complex questions with simple answers. If there are no simple answers, people tend to look for the man on a white horseback.” Liebman accused those on the New Left of crucifying Hubert Humphrey for his support of the Vietnam War. Halfway through the question and answer session, 35 students stood up from their seats, turned their backs to Liebman and walked out of Rosse Hall while administrators in the audience shouted at them to stay.

The walkout was organized by the Kenyon Committee to End the War in Vietnam, referred to in short as “the Committee.” Previous to the walkout, the Committee had picketed U.S. Army recruitment drives on campus, prompting a debate over on-campus protest rules. The Committee made several efforts to publish their own student newspaper, believing that the Collegian had too many ties to the College’s administration to accurately report on campus life. On the Thursday before MDA weekend commenced, one of the founding members of the Committee, Steven Silber ’71 released a statement explaining the Liebman walkout and detailing some of the organization’s long-term goals, mainly the complete abolition of the liberal arts curriculum, which Silber called “archaic” and “an absurdity.”

“The problem we are really dealing with at Kenyon is a microcosm of what we are trying to deal with in the country at large,” said Silber. “Is this a truly open society?”

The Committee’s tactics were an anomaly at Kenyon, where members of what might be deemed the “activist left” mainly expressed themselves through long-form discussion. A key facilitator of these discussions was the late chaplain and professor of Religious Studies Don Rogan, who hosted a anti-war discussion group with students and faculty, as well as holding regular informal meetings on the floor of the Church of the Holy Spirit. Conversations were lengthy and wide-ranging, with a mind towards allowing students to vent their frustrations and speak their mind. “They were talking about things like Bob Dylan, who had been at Kenyon the year before we came,” said Sally Rogan, Don Rogan’s widow. “Things that were on their mind, like the Beat Generation… Students were really just desperate. They could see that the Vietnam War was going to affect them personally, that they might actually be asked to die. The draft was very real.”

Kenyon students were not just the subjects of these historical events. They also made them. One regular attendee of Rogan’s meetings was Terry Robbins, a young radical and member of Students for a Democratic Society, an organization that had organized the student occupation of Columbia University and played a large role in the protests at the 1968 Chicago DNC. At Kenyon, Robbins founded his own chapter of the SDS in 1965, but membership never exceeded 10 or 12 students. In 1969, Robbins and 10 others established the Weathermen, a more militant offshoot of the SDS. On March 6, 1970, a stockpile of explosives went off in the Weathermen’s Greenwich Village townhouse, killing Robbins and two fellow members.

Rogan was close with Robbins, close enough that he was interviewed by the FBI after Robbins’ death. Sally Rogan remembers that while Robbins was a student, Rogan was concerned by the intensity of his political ambitions. “He had an extremely strong point of view,” Rogan said. “As part of the Kenyon tradition, you let people speak. But they were very worried about him when he left.”

In the year between Robbins’ penning of the Weathermen’s manifesto and his death, Kenyon College had begun its experiment with coeducation. To many, the women’s college offered the promise of more of the social change that MDA weekend had helped to spur on. At the same time, the first year of women saw first-hand how much further the College had to go to shake off an “old boys’” culture of binge drinking, sports teams and fraternities. When Julie Miller Vick ’73 arrived at campus, she was told that because the women’s dorms were still under construction, she would be living with the family of a math professor. “We were really not Kenyon students,” said Vick. “We were students of the coordinate college. We did not get to sign the matriculation book. Most of us didn’t do that till our 20th or 25th reunion.” Students of the coordinate college remember several professors publicly professing their annoyance at having to teach women. Rules around sex were incredibly strict, and were enforced by a society that did not encourage the sexual freedom of women. Vick had heard of one student whose parents found her in bed with her boyfriend and immediately withdrew her from the College. Women had only recently been granted the ability to open their own bank accounts, and were still unable to take out a loan independently. Visiting one of her classmates’ dorm rooms, she found a canister of mace in a purse. Having never seen mace before, she examined the tube, accidentally spraying the solution into her eyes. The social structure of the College seemed to be in flux. "I think there was a lot of uncertainty about he roles of women," said Charles P. McIlvaine Professor of English Adele Davidson’ 75. "Women wanted to prove themselves in the classroom, and I think I kind of bought into that, in a way.”

“We really just took it in stride,” Vick said. “We were going to college. This was our first time, what did we know about what college was like?” Vick remembers seeing “Like it or not” t-shirts worn around campus, shirts which Davidson described as "a shorthand for anti-authoritarianism." As a woman friend of the Archons (the group called themselves the “Archettes”), Vick was regaled with tales from the weekend and its aftermath.

Within the first class of women, there was a persistent question of whether or not to form sorority chapters on campus, a discussion that was colored by the atmosphere of anti-authoritarianism at the time. "There was a kind of sense of not wanting to do that, [not wanting] to be exclusive," said Davidson. "People were anti-official organizations, generally." With the arrival of the Women’s College came a sense of new possibilities for the College.

In the statement he published in The Collegian, Silber stated his hope that the women’s college, which would open the following year, would begin a new and better era at the College. “When the women’s college comes, instead of clinging to the past, as we’re going to do, I would really hope that we would become a college of experimentation,” Silber said. “When you’re not changing, you’re dead; this place has been dead for a long time.” While the utopian visions of the revelers of MDA weekend did not come true, the ripples of the weekend were still felt across campus.

Kenyon is a sheltered place, one that has, since its founding by Philander Chase, prided itself on being a refuge from the hustle and bustle of day-to-day life. After Kent State in 1970, Kenyon was one of the few colleges in Ohio not to cancel classes and comprehensive exams, opting instead for a series of student-led discussions. However, it is impossible to keep those barriers up for very long. When it comes to the history of America in the 1960s, MDA weekend is a proverbial drop in the bucket, a sudden and astounding flare-up of anti-authoritarianism that was suppressed almost as quickly as it came into being. But if we look deep enough, we can see the entirety of the 1960s — the tension, the hope, the desire of young people to escape a world that they saw as irrevocably doomed. And if we look even harder, we might see, inside this brief period of Kenyon’s history, a blueprint for the College’s future.