Mount Vernon's Blackface Minstrel

Every August, Mount Vernon comes alive for the Dan Emmett Music and Arts Festival, named for a blackface performer. Members of the Kenyon community push back.

In August, Renee Romano’s son came to her with a question.

He was required to play at the local Dan Emmett Music and Arts Festival as a member of the Mount Vernon High School band but did not want to; the festival is named after a famous blackface performer.

“He asked if it was okay if he ‘took a knee’ at the festival to protest, essentially, that [he was] being asked to play at this festival that is named after someone whose art form demeans his humanity,” said Romano, who is a professor of Africana Studies at Oberlin College and the wife of Kenyon President Sean Decatur. “I thought, I need to start a conversation.”One afternoon later that month, about 35 Kenyon staff and Mount Vernon residents filled the living room of Cromwell Cottage to talk about the Dan Emmett festival.

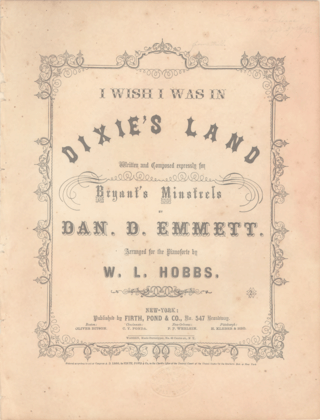

In the 19th-century, Emmett composed the song “Dixie,” famous for its use by the Confederate army, as well as many other less controversial popular American arrangements. Romano does not feel that there is anything offensive about the festival itself; rather, she takes issue with the festival’s name. “If you are going to reference history [and] commemorate something which happened in the past, you have to understand that entire history — and you better own it,” she said.

Romano is not alone in her issue with the festival. At the meeting, many expressed discomfort with the festival’s name. Some proposed eliminating Emmett from the festival entirely. Others felt that by changing the name, the town would be censoring local history, and they did not want to make any changes because of “hurt feelings.” One woman at the meeting argued that Emmett was “one of the good guys.”

“It was a substantive conversation, but I felt like it was jumping fourteen steps ahead,” said Romano. “I was not telling anyone to storm the barricades and demand that the name be changed.”

The Dan Emmett Music & Arts Festival, held one weekend every August, is centered in Mount Vernon’s main square. Tents line the sidewalks, filled with artisans selling crafts. Food vendors fry vegetables, pop kettlecorn, and roll gyros. Young boys in camouflage chase each other around a bouncy castle, decorated with cartoons of firemen. There is a fiddling contest, a vocal contest called “Knox Idol,” and a pancake breakfast. A Christian group sings hymns early Sunday morning behind the car show. Over the course of four days, 700 musical performers grace the festival stage. In the square stands the Soldiers’ Monument, a statue of a Union soldier, posing with his hand on his rifle on top of a long pillar, facing south.

Emmett, the festival’s namesake, was born in Mount Vernon in 1815, the son of a blacksmith. In 1832, he ran away to join the army, where he played the drum and fife in marches. He later tried out his musical talent in the circus, where, along with collaborating musicians Billy Whitlock, Frank Brauer, and Dick Pelham, he founded the Virginia Minstrels, the first blackface minstrel troupe. The group popularized blackface performance by playing off of a combined fear and fascination with southern black Americans amongst white, northern, urban audiences. They broke up six months later after a disagreement while on tour in London, and started their solo careers in different corners of the country. In doing so, they make minstrelsy the most popular genre of music in America.

Dan Emmett claimed credit for composing many of the songs the Virginia Minstrels performed. “Dixie” is their most famous, featuring nostalgic lyrics which pine for a “lost” plantation South, written in an exaggerated phonetic parody of 19th century African American speech patterns. It reached the South at the same time as the secession of the southern states from the Union, and the song was unofficially adopted by the Confederacy in the early 1860s. It was played at the inauguration of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, irrevocably linking the song and the confederacy in the eyes of many.

Yet it is difficult to say that the song “Dixie” belongs to anyone at all. The sheet music was released without copyright, and its lyrics were adapted countless times during the Civil War, sometimes in favor of the Union, other times in favor of the Confederacy. Despite his later expressions of sympathy with the South, Emmett supported the Union during the Civil War, and “Dixie” was used by abolitionist groups at the height of its popularity.

Judy and Howard Sacks, retired Kenyon professors of American studies and sociology, have been thinking and writing about Emmett and his place in the American musical tradition since the 1970s, when they first moved to the area. Their book, Way Up North in Dixie, has caused controversy both with the Mount Vernon Historical Society and the community at large because of its claim that the lyrics to “Dixie” were written by a black performing family, the Snowdens, who moved to Mount Vernon in the early 1800’s after being freed from slavery in the tobacco plantations in Maryland. When it comes to the Dan Emmett festival’s name, the Sacks would like it to provoke conversation about this history.

“Use it to have a conversation about blackface minstrelsy and its influence locally and nationally,” Howard Sacks said. “Use it as an opportunity to tell the story of the Snowdens.”

In Mount Vernon, the figure of Dan Emmett continues to divide black and white communities.

“The white community in Mount Vernon has placed a lot of stock in creating Dan Emmett as a local hero, the local hero,” Judy Sacks said, “and there’s a lot of mythology and hagiography about him. In the black community … they tie Dan Emmett to the problematic nature of minstrel shows, blackface, and social oppression of actual African Americans.”

Ric Sheffield, professor of Sociology and legal studies, does not remember ever attending the Dan Emmett festival while growing up in the rural outskirts of Mount Vernon. “I knew that I would not have been welcome at or comfortable at a Dixie Day celebration.” Sheffield said. “I used to joke as a teenager that I lived in the ghetto of Mount Vernon … there might have been six houses next to each other with black people, but they were all family.”

Although sparse, the black community in Mount Vernon has played an integral role in the town’s history since its founding in 1805, when it was a frontier town seen as free from the social moors and violently oppressive structures of the South. Members of this community have been wary of the festival ever since its beginnings under the name “Dixie Days” in the 1950s.

But the borders between Mount Vernon’s black and white communities are not always consistently distinct. Sheffield learned later that in 1959, an African American contestant in the Miss Dixie Days beauty pageant finished second place, and in the 1970’s, members of the local black Baptist church performed in a local theatrical production that portrayed the Snowden family. Sheffield was surprised to learn that the local African American community was so involved with the local festival.

for the festival divorced from its name. “I mean, what would it become? Would it just be a Mount Vernon Festival? Where’s your branding?”

Associate Professor of English Jené Schoenfeld supports changing the name. She does not think giving more historical context about Emmett will make the name acceptable. “I like the idea in principle, but I don’t see it happening in practice. I think that if people are either going to [eat] funnel cake and listen to their fiddle contest, they’re probably not going to show up if a workshop is held discussing the history of minstrelsy or who Dan Emmett is really.”

Schoenfeld, who lives in Mount Vernon, occasionally attends the festival with her children, as she did this year. “I was there when the news about Charlottesville came in. I felt sick, and I felt like I needed to leave, because I did not want to process news about racialized violence at a festival celebrating someone who is known for a racist art form. That dissonance was profoundly disturbing,” she said.

Though Schoenfeld understands Mount Vernon’s desire to honor a local hero, she believes it is problematic to celebrate someone who is famous for blackface minstrelsy.

Pat Crow, the current organizer of the Dan Emmett festival, works from an office next door to the renovation site of Mount Vernon’s Woodward Opera House. Crow’s office oversees several downtown construction and attraction projects.

Crow believes that most festival staffers would walk from the project in the event of a name change. “They don’t want controversy. If it turned into a major issue, I think that I’d have trouble keeping the team together. They don’t want people hovering over them telling them they’re evil, or bad, or the basis of what they’re doing is wrong. I think it’d be a giant disservice to these folks to view it that way.”

Crow is primarily concerned with conserving freedom of speech in town. He said, “We’re having this conversation across the United States about confederate statues, and everything else, and just because somebody says they’re offended, it doesn’t mean that you should change what you do. I could go through a whole laundry list of ways I get offended each and every day, but that’s life, we move forward.”

Pat Crow noted that that the slogan of the Dan Emmett festival is: Celebrate the Legacy. “Regardless of changes in political feelings, no one will deny his impact on American music,” Crow said.

Minstrelsy laid the foundation for vaudeville, which evolved into ragtime, the precursor to jazz. For some, however, Emmett is part of a long tradition of the white appropriation of black art. “Black musical traditions plus white artists equals a pop sensation,” said Howard Sacks. “It goes: Gene Rogers, Bill Monroe, Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, Vanilla Ice, right up to the present. It’s a successful formula.”

Even in Mount Vernon, Emmett’s legacy reverberates beyond the festival. An elementary school in the town is named after Emmett, and every third grader in the school district learns about him as part of the social studies curriculum, which is centered around local history. They visit the historical society, where they are given a tour on the musician’s life. In class, students read an abridged biography of Emmett that explains blackface minstrelsy and includes Sacks’ research. They learn that Emmett’s signature artform is now considered offensive, and that people no longer perform in blackface.

Even Kenyon is not immune to Dan Emmett’s legacy. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, first-year initiation included a blackface minstrel performance. Much like the First-Year Sing today, the event incited the passion of students. The Kenyon Collegian’s report on the Freshmen Minstrel of 1919, for instance, noted: “Cheering and jeering struggled for supremacy as the pseudo-actors mounted to the stage.”

For the 1909 event, the Collegian offered a more complete description of the first year students: “Blackened and trembling, they reminded the onlooker of the days of slavery … However, before the programme was fairly under way, every man realized that he was not among the good old Southern entertainers, but only just a common bunch of Freshmen.”

The last reported Freshmen Minstrel occurred in 1920; forty years later, in 1960, the college graduated its first black student. In 1992, the college inaugurated the Snowden Multicultural Center, a program house for educating campus about cultural diversity, named after the musical Snowden family.

The conflict stands between those who want to preserve and those who want to broaden local history. One side is concerned with keeping Mount Vernon’s rural character alive in a turbulent political landscape. The other sees the festival as downplaying the more uncomfortable aspects of local history in favor keeping the peace.

Whether or not any actions are taken, Mount Vernon itself is changing. Today, it is host to people of all generations, some of whom have never heard of Emmett.“It’s hard to talk about Mount Vernon as monolithic,” Judy Sacks said. “There are the people who are the old guard, there’s black community, the white community. Young versus old. There are a lot of people who are new here, who don’t even know who he is.”

At the heart of this conflict is a dissonance in opinion of what the future of Mount Vernon should be. When asked what they would propose as a solution, both sides stressed the importance of communication. “Those who spend their days in their bubble,” said Crow, “watching Fox News, CNN, or MSNBC — they’re the worst. Get out there, meet real people.”

Renee Romano encouraged the same of Kenyon students but understood the hesitation some feel to involve themselves in a community they only temporarily call home. “The thing with transient communities is that you have as much right while you’re living in a community to be a part of that community,” she said, “but that means you really have to be a part of it — you have to listen. You need to learn.”