New Heights on the Hill

One crisp autumn morning in 1933, Marian Cummings headed into Gambier to bring her husband Wilbur, who was in town for a Board of Trustees meeting, back home to New York. There was only one problem: She needed a place to land.

Rather than visit the College by car, train or bus, Marian had decided to take her Stinson Reliant airplane out for a spin. This was typical for Marian, who had long displayed a love for flying. According to College Historian Thomas Stamp, Marian was said to be the first woman in the United States to hold a commercial pilot’s license.

Her husband had told her to land in Newark Airport near Granville, but Marian had other plans. She wanted to improvise a runway, and promptly descended to a field in southeast Gambier.

The field turned out to be a better landing strip than she expected. Aside from the unmown grass, the site was an almost perfect ready-made airfield.

Marian’s enthusiasm for aeronautics spread to her whole family — including Wilbur. Inspired by his wife’s landing, Wilbur offered to hire out road rollers to flatten the earth, build a hangar and transform what was once an unused space into an operational airfield. However, the original area was not used for long. Within a year, Wilbur had moved and expanded the hangar, building a more substantial airport where the lacrosse and baseball fields are today.

On April 21, 1934, Port Kenyon was dedicated in front of students, professors and various visiting guests — including Governor of Ohio George White. That day, Port Kenyon became the first officially recognized collegiate airport in the United States.

Originally, the airport was only meant to accommodate the planes of alumni when they returned to the College for events. Its purpose expanded when students, inspired by the aeronautically-inclined alumni, wondered if they could learn to fly too. Spurred on by the aspiring pilots, Wilbur decided to push the College to open a fully fledged aeronautics program that could earn students official Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) licenses.

The College faculty originally objected to the prospect of an aviation program. The aeronautics school, they feared, would compromise Kenyon’s commitment to the liberal arts by shifting its focus to vocational training.

Wilbur disagreed. He believed aviation was as integral to a young man’s education as mathematics, biology or English. “Such subjects as navigation, meteorology and aerodynamics,” Wilbur said in a 1935 New York Times article, “are profound enough to be placed in any liberal arts curriculum.”

The administration soon bent under Wilbur’s pressure. Within a few years, the Wilbur L. Cummings School of Practical Aeronautics was born.

The decision, though novel, was not unconventional given its historical context. World War I showed the world airplanes were not just a novelty, but an increasingly vital tool that a modern nation would need in order to keep up. As time went on, flight schools began cropping up all over the country to teach a new generation of Americans who saw profit in learning how to fly.

During the initial push to establish the program, Wilbur’s arguments were similar. He believed that flying would be vital to a Kenyon student’s success in a modern world. As reporter John Tunis agreed in an article about the nascent flight school in The Sportsman Pilot magazine, “Before long these men will need a plane just as everyone today needs an automobile.”

Wilbur took charge of the project himself and raised enough funds to stock an aeronautics laboratory in Higley and purchase two planes: a 100-HP Kinner K-5 and a Fledgling, both of which were painted purple and emblazoned with a big “K.” These funds also went toward endowing the department with a chair that would help pay the salary of Donald McCabe Gretzer, an experienced teacher and former test pilot who instructed Kenyon students as they took to the skies for the very first time.

At the end of the program, participating students could earn an Airline Transport License, the highest level license available to civilian pilots. This would allow all students who completed the course of study to pilot scheduled aircraft services — or, in today’s parlance, to fly for any airline that hires them.

The school established two groups of courses: ground school instruction and flight instruction. At ground school, held in the laboratory in Higley, students met three hours a week and worked toward the Department of Commerce’s required 25 hours of study on the principles of aviation. This included such subjects as engine carburetion, construction, inspection and maintenance. The course also involved 30 hours of more academic subjects, like aviation history, flight theory and aerodynamics. Finally, the students would satisfy several seven to 15-hour requirements on navigation, meteorology, radio communication and, for emergencies, parachute packing.

For all of the above, students were able to receive credit. However, they weren’t so lucky when it came to their in-air instruction; their time spent in flight school counted as an extracurricular. The flight school, which required 10 hours in the plane with an instructor and 25 hours of solo flight, totalled over 100 hours. Gretzer was a busy man, as he taught all the courses both in the air and in the classroom.

The aviation program advertised its services across the town and state.

Over the years, the school of aeronautics became a well known (if not slightly niche) part of Kenyon life. In 1935, a group of Kenyon students decided to take to the skies on a more extracurricular basis with the Kenyon Flying Club. As a part of the National Intercollegiate Flying Association, the club competed with various other colleges, such as Duke University, Purdue University and Stanford University, all of which had their own flying teams.

The proximity of Port Kenyon proved to be a considerable advantage to the team. The Lords won the National Intercollegiate Air Meet in 1937 and 1939, and tied for first place with Stanford in 1938. The air meets consisted of several events, which ranged from mid-air maneuvers to bombing — or more accurately, dropping a flour-filled bag onto a target.

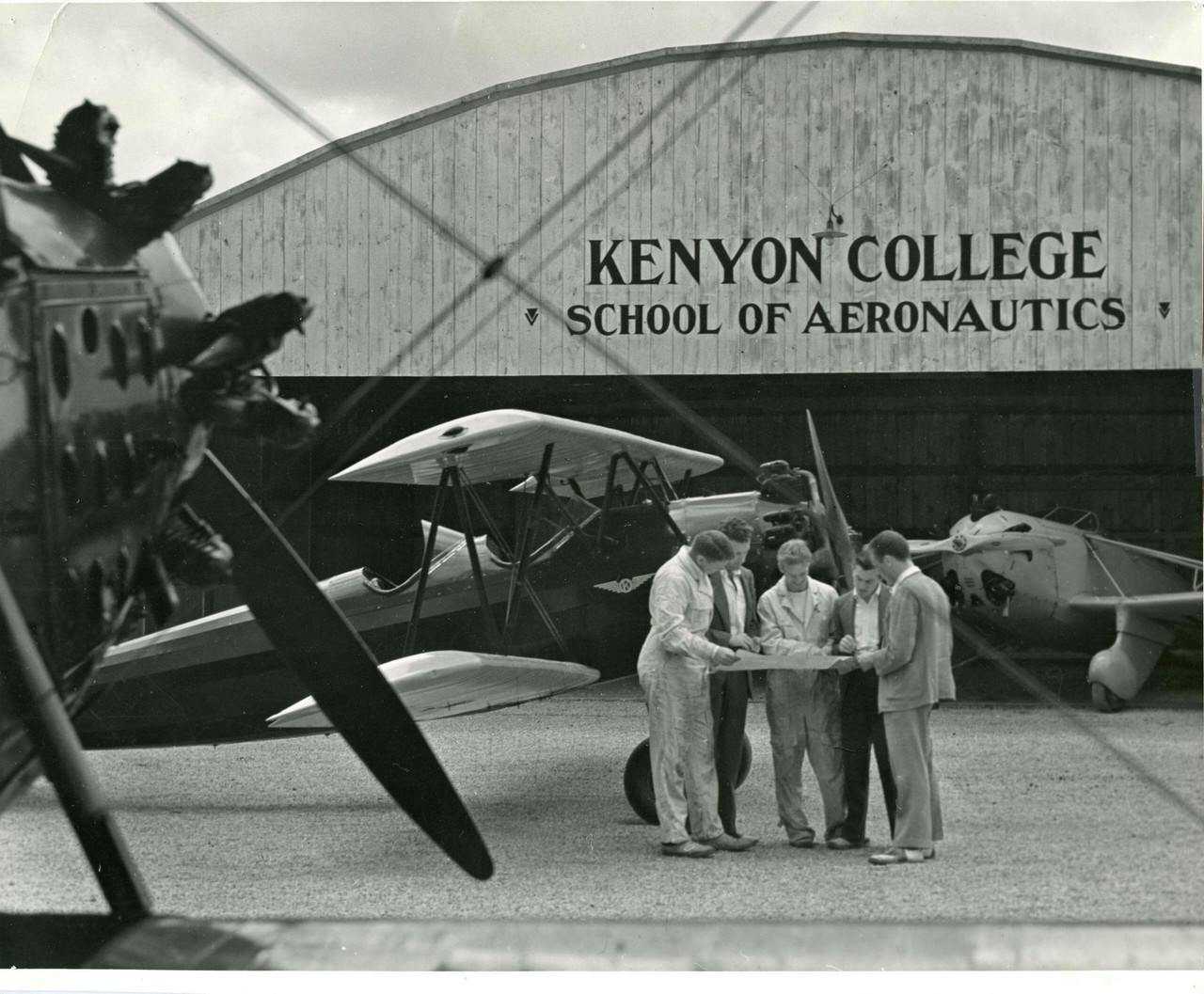

Students enrolled in the College’s School of Aeronautics gather outside its hangar to look over flight plans.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Greenslade Special Collections and ArchivesPort Kenyon’s purpose shifted again during the late 1930s as tension grew in Europe. When the U.S. received word that Italy and Germany were sponsoring programs that sent thousands of young fliers into the sky, the U.S. correctly guessed that it was a covert effort to train for war. As a response, the U.S. launched the Civilian Pilot Training program. Kenyon, with its considerable resources, was enrolled in 1939.

Courses in the training program were only available to currently enrolled students, and no changes were made to the Aeronautic School’s curriculum. The only real change the school faced was the influx of federal money into the program — that, and an influx of enthusiastic and poorly-spelled letters from the surrounding countryside inquiring about the program. The College received so much correspondence, in fact, that it prepared a form letter telling prospective students how to apply.

One year later, Gretzer announced his resignation and left the College. His replacement, Hallock Hoffman ’41, was one of Gretzer’s most prominent students and the first choice for the job.

When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, scholastic flying was suspended entirely. Hoffman himself was drafted into the war a year later. Although the school was now officially closed, Kenyon still played a key role in training young pilots. Over the course of the war, the U.S. Air Corps (the early form of what would later become the Air Force) used Port Kenyon to train over 250 pilots for the war effort.

Rodney Boren ’38 served as an active member of the Kenyon Flying Club before becoming a pilot trainer in WWII. In 1947, he was appointed Commander of the Ohio National Guard 121st Fighter Squadron.

A crowd gathers on Port Kenyon’s airfield to watch students take to the skies for the first time.

After the war, Port Kenyon never regained its former glory. While flying club operations could continue as long as the field was insured, the College was unable to offer any formal classroom instruction. This meant that the only relationship students had with flying was strictly extracurricular. This situation deteriorated further when tragedy struck the program. In May of 1956, Charles Frederick Walch ’57 and Arnold Perry Gilpatrick ’58 were on a recreational flight above Gambier. A local farmer reported the distinctive sound of a sputtering engine and looked up to see a plane falling from the sky. Both students were killed in the ensuing crash.

This tragic event cast a shadow over aviation at Kenyon. In an Alumni Bulletin article, Andy Bourland ’73 remarked that when he arrived at Kenyon in 1969, flying had almost disappeared. “They did mow the runway a couple times a year,” he said. “We hired a farmer to make the field a little bit better and he made it a little bit worse. There were probably a few resident groundhogs.”

In 1972, the College finally questioned the validity of the field itself. Citing mounting insurance cost, the administration asked the FAA to decommission the field.

As of today, there is little that would hint that Kenyon ever had an aviation program. Even the athletic fields that replaced it, affectionately called the “airport fields,” have been renovated and renamed. Besides what can be unearthed in the Archives, what remains of Kenyon’s aviation history is just scattered, obscure memorabilia, and the knowledge that some alumni, upon their return, look not just at the town around them as a source of fond memories, but to the sky as well.