Making Kenyon accessible

Attracting students with disabilities to Kenyon may take more than just renovating buildings.

On a late September evening, Justin Martin ’19 sat in the downstairs Alumni Dining Room of Peirce Hall, eating dinner with friends. The group was laughing at the Kenyon “sad boy” trope they embody. In many ways, Martin is the typical Kenyon student; he shares his combination of sarcasm-tinged wit and genuine passion to make the world better with his peers on campus, and his nuanced analysis of life — his commitment to “never giving a simple answer to anything” — seems destined to help him succeed. But one fundamental difference stands between Martin and the rest of the student body: Martin is in a wheelchair.

In his four-and-a-half semesters at Kenyon so far, Martin has inadvertently become the figurehead of the push towards physical accessibility at Kenyon and beyond. In addition to countless interviews with on-campus publications like The Kenyon Collegian, Martin’s story has also appeared in The New York Times and Huffington Post. Disability Rights Ohio recognized him last winter with their “Courage Award” after he successfully petitioned the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities against a bill that would slash Medicaid funding for in-house providers. His plea garnered attention from the student body and brought physical accessibility issues into the limelight.

Yet Martin almost did not make it to Kenyon at all. In high school, Martin applied for the Kenyon Review Young Writers Workshop, a summer program for high school students interested in creative writing. He hoped to prove to his parents that he could live on his own and succeed far away from home.

His application was denied. The program administrators decided they could not accommodate his disability. It took a long conversation and multiple back-and-forths between the administrators and Martin before the program administrators agreed on a plan and decided he would be able to attend.

Martin’s story reveals a fault in how colleges treat potential disabled applicants. “Even Kenyon didn’t think that Kenyon was the place for me until Kenyon was the place for me,” he said.

Kenyon’s method of increasing physical accessibility on campus has, through recent years, been largely focused on the removal of physical obstacles. Erin Salva spearheads Kenyon’s accessibility changes as the director of Student Accessibility and Support Services (SASS.) Without improving our facilities, she said, Kenyon has little hope of attracting other students with disabilities.

“The better we get at accessibility, the more likely people are to come because this is an inviting campus setting. Promoting the fact that we are intentional about their success and thinking about accessibility up front makes our campus more attractive,” she said.

The original barrier removal process began in February of 2001, when the president at the time, Robert A. Oden, commissioned an Accessibility Review Committee. In July of the same year, the committee published its findings that Kenyon was not nearly accessible enough and was losing many quality students.

In a letter dated May 16, 2001, a young, prospective student in a wheelchair explained to admissions that, although he wished to attend Kenyon, he was unable to come. “I found it regrettable that your facilities were simply not conducive to a person in a wheelchair,” he wrote.

In 2001, the barrier removal project spearheaded the renovation of eight campus buildings, including Pierce Hall and the Olin and Chalmers Memorial Library. Since then, Kenyon has gone from being mostly inaccessible to people in wheelchairs to over 70% accessible. Now the school is on track to be 91% accessible by 2020, with Ascension Hall scheduled for renovation in the next six years as part of the plan for the recent $75 million dollar donation.

“We have come a long way, but we have miles to go,” Salva said.

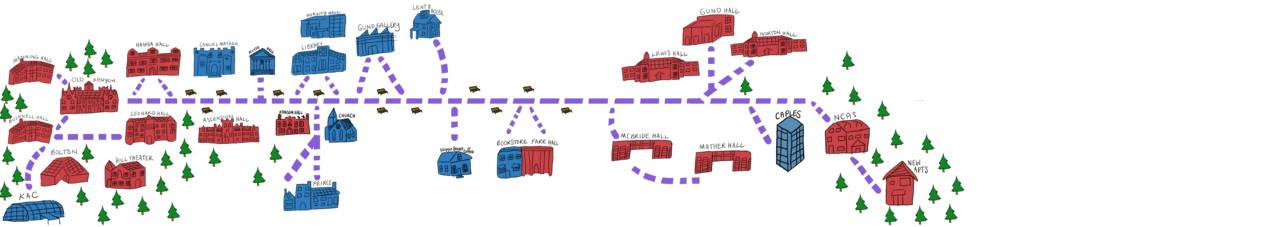

Many of Kenyon’s buildings are inaccessible to people in wheelchairs. Illustration by Bronwyn Brown.

For Martin, the goal of maximal physical accessibility cannot be reached soon enough. “What keeps me up at night, and what should keep the Kenyon administration up at night, is that you’re taking a big gamble when you [delay making resources accessible]. The gamble that you’re taking is that the next John Green isn’t disabled, or the next Allison Janney isn’t disabled. You don’t know that. You don’t know who you’re missing out on, by definition, because you’re missing out on them,” he said.

While Martin is happy about Kenyon’s progress, he thinks anything short of 100% accessibility is not enough. He said, “We don’t know how much talent we’re losing, how much talent is not coming to the hill, because it’s not yet 91% accessible. Even when we make it 91% accessible by 2020, what if something in that 9% is somebody’s thing? That 9% could be the 9% that keeps other disabled students from deciding to come to Kenyon.”

On top of this, Martin thinks Kenyon’s commitment to accessibility must be conscious and continuous; as with racism, there is no magic light switch that will immediately fix systemic problems. Kenyon must change its culture to highlight the work of disabled persons. Martin explained that classrooms need to prioritize disabled voices and showcase work from disabled people. Extracurriculars and social events should be able to include everyone.

On this front, Martin still has reservations. He said, “My worry is that we’re going to get the physical accessibility taken care of, and then Kenyon is going to just expect the disabled students to come pouring in, and that might not happen. And once that doesn’t happen, they’re going to see it as, ‘Well, we wasted all this money,’ versus ‘We need to do more to actually welcome disabled people here.’”

In a study conducted by the University of Washington this year, researchers found that only 6% of the American undergraduate population identifies as disabled, and of that percentage, only 7% have conditions that limit mobility. It is not just that these students are not coming to Kenyon; it is that they are not going anywhere.

Many factors influence any given student’s decision to pursue postsecondary education: Affordability, distance from home, and academic performance are a few of them. For students with physical disabilities, these factors are magnified tenfold. Affordability becomes not just paying for tuition but also paying for in-home providers, medical care, and equipment.

Martin knows this from experience. Before he moved into his first-year Lewis Hall residence, both he and the college administrators believed the state government would pay for an automatic lift that would help him use the toilet. Then, days before Martin moved in, he learned the government would not pay for the lift. “I thought I wasn’t going to be able to go to college,” Martin said.

In the absence of governmental funding, Kenyon (lobbied heavily by Erin Salva) agreed to pay for it. But situations like this bar many disabled students from attending college. Martin said he fully understands that he is one of the lucky ones.

Even some of the buildings Justin Martin ‘19 can technically enter are not fully accessible to him, or to others with physical disabilities. Kenyon is slowly working to change that. Photos by Eryn Powell.

These are only some of the difficulties students with disabilities face if they want to attend college. Because Kenyon is a remote, selective school, disabled students may not perceive it as a realistic option, Martin said.

Several programs across the country allow students with disabilities to have a college-like experience without facing the barriers presented by accredited colleges. However, many of those programs, such as Transition Options In Postsecondary Settings (TOPS), which operates out of The Ohio State University, do not offer real college diplomas. TOPS is marketed toward students with intellectual or developmental disabilities, and a large part of the program’s focus is developing skills in independent living, career readiness and self-determination.

Wright State University, an accredited public school in Dayton, Ohio, offers extensive support to students with disabilities, but, Martin explains, “The jokey nickname of Wright State is Camp Wright State, i.e. the academics at Wright State are maybe not as rigorous as some people would like them to be.”

This leaves students with physical disabilities who can perform at high intellectual levels with little chance to pursue the kinds of curricula offered at liberal arts schools. The idea that students with disabilities can attend schools typically imagined to be for able-bodied students is still novel; the physical accessibility initiatives that Kenyon is working toward have only existed for sixteen years of the college’s 193-year history.

“There’s a prevailing notion among a lot of high school college counselors and college administrators that if you’re disabled and you’re being considered for college at all, you’re lucky. God forbid you be remotely selective; God forbid you know what you want,” Martin said.

Attracting a greater number of disabled applicants to Kenyon involves more than just making Kenyon more accessible, both physically and culturally.

Martin describes his ultimate goal as this: “If I asked you to think of a Kenyon student, just a generic Kenyon student, you’re probably going to think of a twenty-something, white, cis, straight male. The point at which equality becomes more cemented is when someone hears ‘Kenyon student’ and maybe they think of a disabled person, or a trans person, or a person of color.”