Powering Up

As Kenyon approaches its 200th anniversary, the Magazine examines how a traditionally literary campus is adjusting to the modern age.

On March 24, 2017, the campus and parts of Mount Vernon faced an almost eight-hour blackout. The political science department, looking to fill Assistant Professor Jacqueline McAllister’s place during her leave next year, had to reschedule its Skype interviews with potential candidates. Professor of Japanese Hideo Tomita suspended his midterm because he was unable to make copies of his exam. The library closed early and Kenyon students escaped to Mount Vernon in droves, carrying chargers and drained devices. Among them, Andrea Evans ’19 and Ali Georgescu ’19 took refuge at Panera Bread — one of many establishments that saw an increase in business from, and its light sockets monopolized by, Kenyon students.

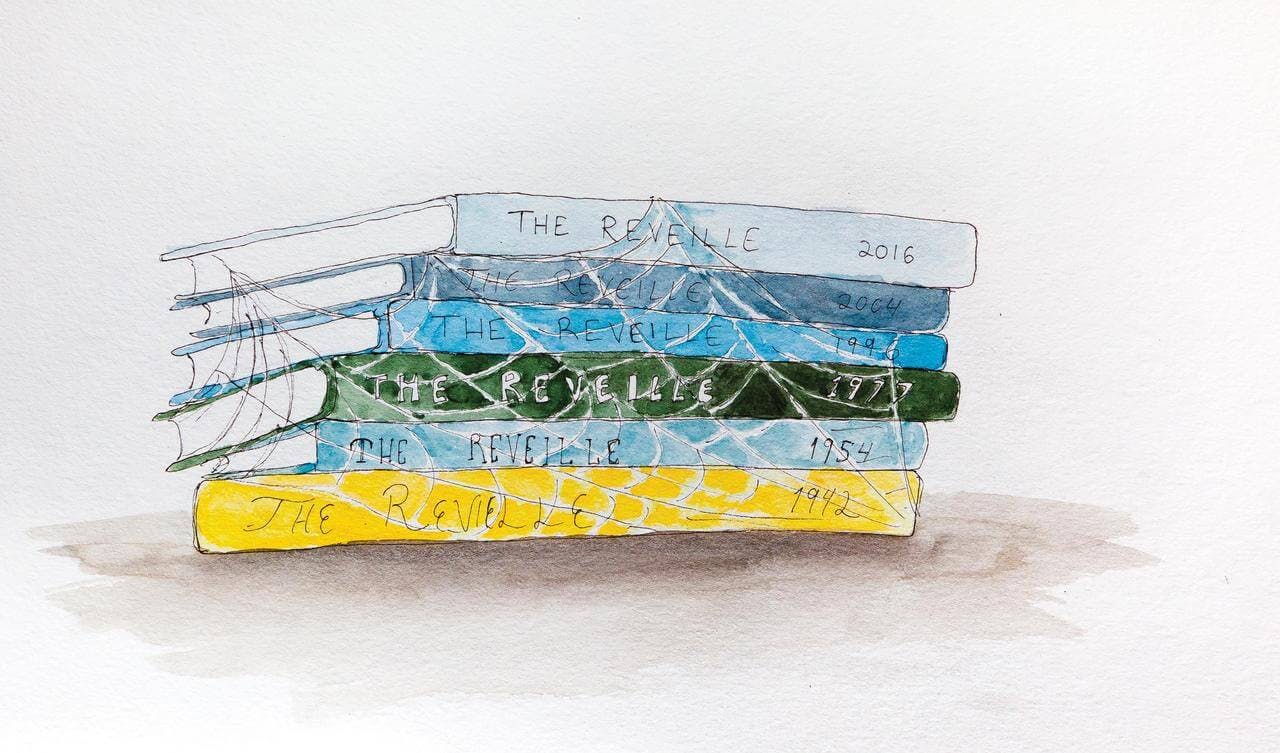

Even for a literary college in rural Ohio, Kenyon is wired and dependent on technology. Professors are integrating digital tools into their classrooms, and the Greenslade archivists are moving Kenyon’s physical records online. This year will also mark two new presences on campus: a smartphone app, Mobile ID, that will allow students to access buildings without their K-Cards, and a website, NetNutrition, that will streamline the process of informing students about allergens contained in food served at Peirce Dining Hall. In just two short years, Olin and Chalmers Library will be demolished, replaced by a new commons with basement bookshelves sealed by electronic locks. And this year will mark the first time in 161 years without a print edition of Kenyon’s yearbook, The Reveille.

Home to The Kenyon Review and the alma mater of a number of successful authors, the college has defined itself as a writers’ school. But as it approaches its 200th anniversary in 2024 and progresses toward its 2020 plan, Kenyon’s priorities may be shifting. As the institution transforms to keep up with a technological age, it must decide which parts of its traditions to maintain or discard. Here’s what’s ahead — and what Kenyon might be leaving behind.

Mobile Integration

In the past, when first years came to campus, upperclassmen warned them not to use their phones on Middle Path — a long-held rule that allowed for more face-to-face interactions. Now, phones are everywhere on Kenyon’s campus — and the College is taking notice.

Recently, the College designed a new app, Mobile ID, to keep pace with Kenyon’s needs and the character of the age. The new app gives students the ability to access a door on campus by entering a code, indicated by a sticker label on the door’s card reader, and swiping right on their smartphones. Supplementing the app, a website at kcard.kenyon.edu will allow students to check their K-Card balance, evaluate their spending history, and disable their cards in the event they are missing or stolen. The website is now active, and Mobile ID will be released this month.

Spearheaded by the Library and Information Services (LBIS), Mobile ID was designed to give students an alternative to calling the Office of Campus Safety. The department spends an estimated 100 hours a month responding to calls from students locked outside their dorms. The office receives 12,000 to 13,000 total calls from students in any given year, according to Bob Hooper, the director of Campus Safety. “[Mobile ID] is a real convenience for students, and it makes the campus a little bit safer,” Ronald Griggs, the vice president of LBIS, said.

Predicting students’ reactions to the new app is difficult. When Kenyon’s identification card, the K-Card, was first introduced in 2007, some regarded it with suspicion. One opinions columnist for the Collegian, E.B. Debruin ’09, wrote an article titled, “Implementing K-Card will make Kenyon just like other, larger universities,” and staff writer Lucas Northern ’10 reported that some students were worried the K-Card would make the campus transactional and impersonal. Today, many students cannot imagine campus life without the K-Card.

Following LBIS’s app, Peirce’s online service, NetNutrition, will be ready in fall 2017 after a beta test over the summer. According to AVI, the company that Kenyon contracts for food services, NetNutrition is user-friendly and allows students to easily filter Peirce dining options that contain milk, fish, wheat, eggs, soy, and gluten.

Garrett Shutler, a 2016 graduate from Heidelberg University, recently became part of the AVI staff. One of Shutler’s many responsibilities is printing allergen labels for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, but he explained that in an age of online marketing and social media, “there is not a lot of pen and paper stuff anymore; everything is moving online. And that’s eventually what [AVI] wants to do.” The paper labels will not disappear overnight, but AVI hopes the accessibility of NetNutrition will whittle down their necessity and render them obsolete. If fully implemented, Shutler explained, the new system will reduce time, costs, and materials for both AVI and Kenyon, as well as stress for students with allergies during the hectic times of the week.

Learning Digitally

Inside the classroom, digital tools are gaining popularity, as well. Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies Laurie Finke sees technology as any other classroom tool — to be used when helpful. She is having her students experiment with a software called Omeka to produce online exhibits exploring the role of commodities in consumer culture. Although Omeka proves a valuable medium for presenting information, Finke admitted the assignments “are murderous to grade.” While a paper takes 30 to 45 minutes to grade, the online exhibits require an hour to an hour and a half. Finke thinks the program is worthwhile, though, as her students can be creative and expressive in thought, learn a new technology, and apply their knowledge to a format other than paper writing. In fact, Finke’s students end up writing more for their exhibit labels than they would if the project was assigned as a paper.

Finke is quick to note that quantity does not compensate for quality. “I don’t want the technology to take over,” she said. “I don’t want the students to get so caught up in ‘how do I do this’ that they don’t actually pay attention to what they’re writing.” Kenyon has a reputation for producing great writers in all majors, and Finke expressed she would rather have her students write something interesting than be overwhelmed with technology. “When the digital stuff starts taking over, then it’s no longer pedagogically useful,” she said.

Preserving the Past

As students are turning towards digital materials, preserving history can be a challenge. The staff of Greenslade Special Collections and Archives, home to Kenyon’s past, are trying to keep pace with the growing electronic age. By scanning the College’s physical records and moving them online, they want to to increase the accessibility of the College’s history. Medieval manuscripts, college catalogues, and the letters of Kenyon’s first two presidents, Charles P. Mcllvaine and Philander Chase, can be found at digital.kenyon.edu, as well as past Collegian issues and editions of the Reveille.

The number of physical records will be lower in subsequent years, though, as the 2016 edition of the Reveille was last in its series and, as College Archivist Abigail Miller noted, student groups no longer submit as many physical records to the Archives. Yearbooks like the Reveille have been disappearing from college campuses across the country because of diminishing interest, from Johns Hopkins University’s, to those of Towson University, Wesleyan, and Purdue. Miller attributed this loss to social media, explaining, “everyone keeps their own records now.” But yearbooks are still “great records of the past” to archivists like Miller; the Reveille traces Kenyon’s history as far back as 1855. Its books are first-hand accounts that historians can hearken back to when researching Kenyon.

Yearbooks have a greater staying power at smaller colleges than they do at larger universities, Miller finds. “When I came here, it was really interesting to me all the traditions and the small community feel,” Miller said. “And I think it’s a big part of why people continue to come back for Reunion Weekend and why people feel connected to the College many, many years on — more so than I think they do with larger institutions.” Miller has not visited her alma mater, the University of Pittsburgh, since she graduated. “I don’t quite feel that pull to go back that I know many of the Kenyon alumni do,” she said.

Some students mourn the loss of the Reveille as their time on the Hill trickles down. “It is disappointing we won’t have a yearbook to commemorate our year,” Eva Buchanan-Cates ’19 said. “Signing the Matriculation book is cool, but in 30 years when I come back with my kids, all I’ll be able to show them is a signature. With a yearbook, my kids can look at pictures and ask me questions about people I’ve spent the last four years with. They can see what was in style and what was happening on campus.”

As colleges move away from yearbooks and students rely on social media as their primary means to record their memories, Griggs wonders, “What’s a record look like in Facebook?” A similar thought was expressed at Kenyon when email became its chief form of communication, he explained. “When the College started using email instead of written memoranda, there was this thought [that] we’re going to lose all this history,” he said. “If you went back and looked at what was going on at Kenyon in 1950, there would be folders full of written memos that would describe what was going on.” Emails sent electronically cannot be easily archived because they might contain sensitive information. LBIS is still struggling today to find a way of ensuring that information is private, but available for the next generation. “What does it look like for the College to preserve its history, while at the same time preserving the privacy of everyone involved?” Griggs asked.

As Kenyon progresses further into a digital age, faculty and students must decide what to keep as a fundamental part of the College and what to let go of and modernize. Griggs said, “Change in the world means that we have to change the way we behave in order to live successfully.” Kenyon must change to stay competitive as a liberal arts institution, but as the College moves forward, it should remember to ensure it is not leaving anything valuable behind.