The Askal

I’m in line at a coffee shop when the boy in front of me turns around and, without introduction, asks if I’m an international student.

“You just don’t look like you’re from here,” he shrugs when I say I’m not.

“From Ohio?”

“From America.”

I do not know how to answer. I never do.

Where are you from? Where are you really from? It is always some iteration of this sequence of questioning, always disbelief in response to my answer. As if I must be lying.

“What does it mean, to look like ‘you’re from here,’” I want to ask the boy long after he’s gone. But I already know the answer.

In kindergarten, waiting in the yard for the school bell, I used to watch the other girls and long after their blonde hair pulled into braided pigtails, their blue eyes so dazzling they were poetic. The kids in school used to compare my teardrop-shaped eyes to mud, my tanned skin bakes dark in the summertime. Pancake face. Potato nose. My features sink into my depthless face, edges smooth, round, like the pullet’s first brown egg in spring.

What does it mean, to look like you’re from the United States?

The kids in school used to ask me why I stood for the pledge if I wasn’t from here.

America is not my face.

______________________

They call them askal in the Philippines, which translates to “street dog” in Tagalog. They’re mutts. Most of them have short coats, pointy ears, and pointy snouts, slender tails that curve towards their backs and a slender frame that comes up to about the average American’s knee. The females’ swollen teats swing from their bodies, hips and ribs jutting through their skin, and the males’ balls hang pronounced between their back legs like two har gow.

Sometimes you’ll come across an askal that has a striking resemblance to the old retriever or lab you had as a kid — the one in Bolinao was half askal, half beagle: “His mother was raped by one of the locals,” the owner motioned to the mother, a purebred beagle resting in the shade of the palms, and doubled over laughing at his own joke.

______________________

Whenever I tire of the tourists that crowd the tattoo shop, I sneak off to the souvenir shop to hang out with Ate Claudine. “How is your work going?” she always asks, motioning to my clipboard and notebook.

Pulling up a chair beside her at a table, I grumble, “You talk to one tourist, you talk to them all.” Ate Claudine laughs. “What about you?” I ask, “How is your work going?”

She points with her lips down the rice terraces: “About to get busy.”

I peer over the edge at the approaching group—about twenty strong and probably from Manila. Coming to get tattoos from Apo Whang-Od.

An askal puppy naps in the corner and I beckon it over with chicken scraps I produce from my dress pocket.

“Look, look at his tail,” I say to Ate Claudine as I rub his belly. “Look how happy he is.” She nods. Smiles but doesn’t quite understand.

“This is probably the first time he’s ever been touched.”

The first man to stumble up the mountain is the tour organizer. He signs in with Ate Claudine who works the environmental fees. Every tourist that enters Buscalan has to register with her.

The man takes a seat across from me and takes a swig from his water bottle. Smiling, he says something to me in Tagalog.

“Sorry,” I say. It’s an automatic response. Without looking up from her clipboard, Ate Claudine answers him. I hear the word English, catch her gesturing towards me with her pen.

“Ay nako! Sorry,” he says. “I thought you were Filipina.”

I tell him I’m half.

He blinks at me. “I don’t understand. But you don’t speak Tagalog?”

Chewing on my lip, embarrassed, I explain, “My mother is Filipina, my father is Vietnamese. English was their only shared language. I grew up in the United States.”

Understanding blooms on his face. He nods, laughs. “So you are like one of those,” he says. He gestures to the askal puppy lying at my feet.

I reach down to itch behind the mutt’s brown ears and she stretches, yawns, her tail lazy tail lolls back and forth. “In a way, I suppose,” I say back.

______________________

Where there are people in the Philippines, there are askal. They fight feral cats over food scraps in the streets of Manila — and risk becoming food scraps themselves if they’re unlucky enough. In Baguio the askal dodge jeepneys and taxis, while the more fortunate purebred chow chows walk leashed beside their owners. The askal in Buscalan dodge kicks when they’re too slow to move off of pathways, bicker with the chickens and pigs across bowls of rice and water. After every meal, I sneak my adobo scraps into the pocket of my dress and wander around until I find a mother with a pup or two in tow. Squatting down, I place what remains of my dinner before them as the mother ventures towards me, head low and eyes searching. It’s only when I walk away that I hear the crunch of teeth through bone.

______________________

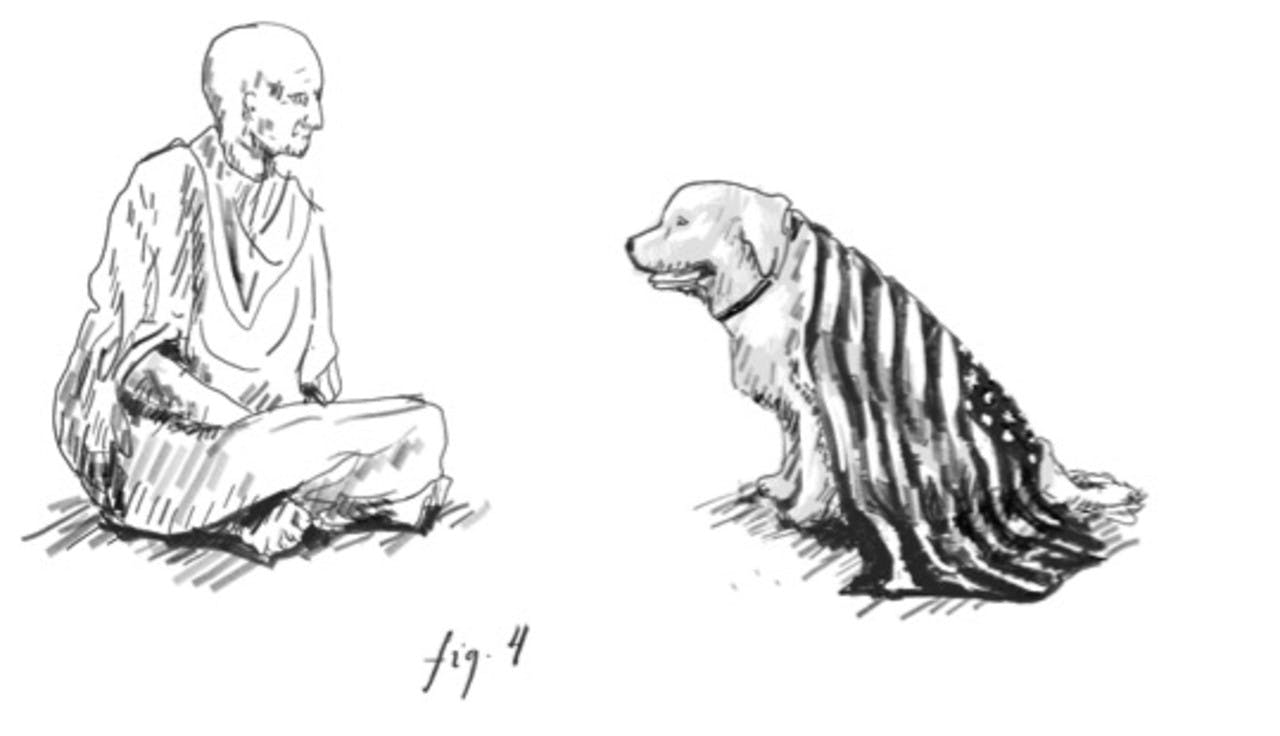

I once heard a story about a Buddhist monk who, when asked what he’d choose if he could decide his next reincarnation, said he would want to come back as a dog in America.

“The way people love their dogs here…” my father once explained, “we didn’t have that with our dogs back in Vietnam. Your mother didn’t have that with her dogs in Cebu.” Dog ownership in America is, comparatively, special. It is unique that so many dogs in this country sleep at the foot of their owner’s beds at night, unique that we love them in the way that we do, call them family, celebrate them, grieve over them.

What must it be like to be a dog? To have someone to call your owner? To have someone, someplace, to return to when the sky turns red and the sun sinks back into the earth? To be loved whether your face is flat or if your tail is docked, loved whether you’ve got three legs or two — there is no wrong way to be a dog.

I think of the monk who wished to come back as a dog in America. I think of the askal. Give me a country that claims me as its own. Give me a country that lets me call it home. ■