The Lords and the Lords

Kenyon’s historical relationship with its namesake

On August 17, the sixth Lord Kenyon, great-great-grandson of a major initial donor and namesake of Kenyon College, passed away at his home, the Gredington estate in Flintshire, Wales. The barony was inherited by his eldest son, Lloyd Nicholas Tyrell-Kenyon. While the College’s relationship to the Kenyon family is now largely ceremonial, the two Kenyons have still come into contact with one another over the years.

“Informal” was how President Sean Decatur characterized the relationship of the Kenyon family to the College in a Sept. 19 article for The Kenyon Collegian. College Historian and Keeper of Kenyoniana Tom Stamp ’73 agreed. “It was certainly more formal at the beginning,” he said, referring to the the first decades of the 19th century. While Bishop Philander Chase was fundraising for the establishment of an episcopal seminary in Ohio, he struck up a friendship and philanthropic relationship with an early benefactor, the second Lord Kenyon. But even then, Stamp said, it was relatively informal.

In more recent memory, Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, sixth Baron Kenyon, described his relationship to the College at his 1999 Founder’s Day speech as a “mere accident of birth.”

Still, the relationship retains a prominent role in Kenyon culture past and present. “There is a reason why we’re the Lords and the Ladies,” said Susan Spaid, retired director of events at Kenyon. She pointed out the lingering presence of British tradition at the College. “So many years later, it still conjures up a whole lot of enthusiasm and excitement.”

Lady Margaret Emma Kenyon | COURTESY OF GREENSLADE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES

Lloyd Kenyon, first Baron Kenyon, was awarded his first noble title in 1784. This baronetcy, ranking just below a barony, was awarded to Kenyon for his career in the House of Commons. After a tenure as Master of the Rolls (the second highest judicial appointment in England and Wales), Kenyon rose to the position of Lord Chief Justice, a move which granted him and his descendants the hereditary baroncy.

It is the first Lord’s son, George Kenyon, second Baron Kenyon, after whom the College is named. He was an evangelical Anglican who was instrumental in securing money for the establishment of Chase’s frontier seminary; he readily gave his own money and helped Chase find even more potential donors. The two were introduced by George Mariott of London, and Chase and Kenyon became fast friends.

The Baron’s daughter Margaret even became infatuated with the American bishop: She had an “American frontier” garden constructed at the family home, complete with a log cabin resembling Chase’s early domicile in Gambier.

Since then, members of the Kenyon family have only occasionally come into contact with the college that bears their name.

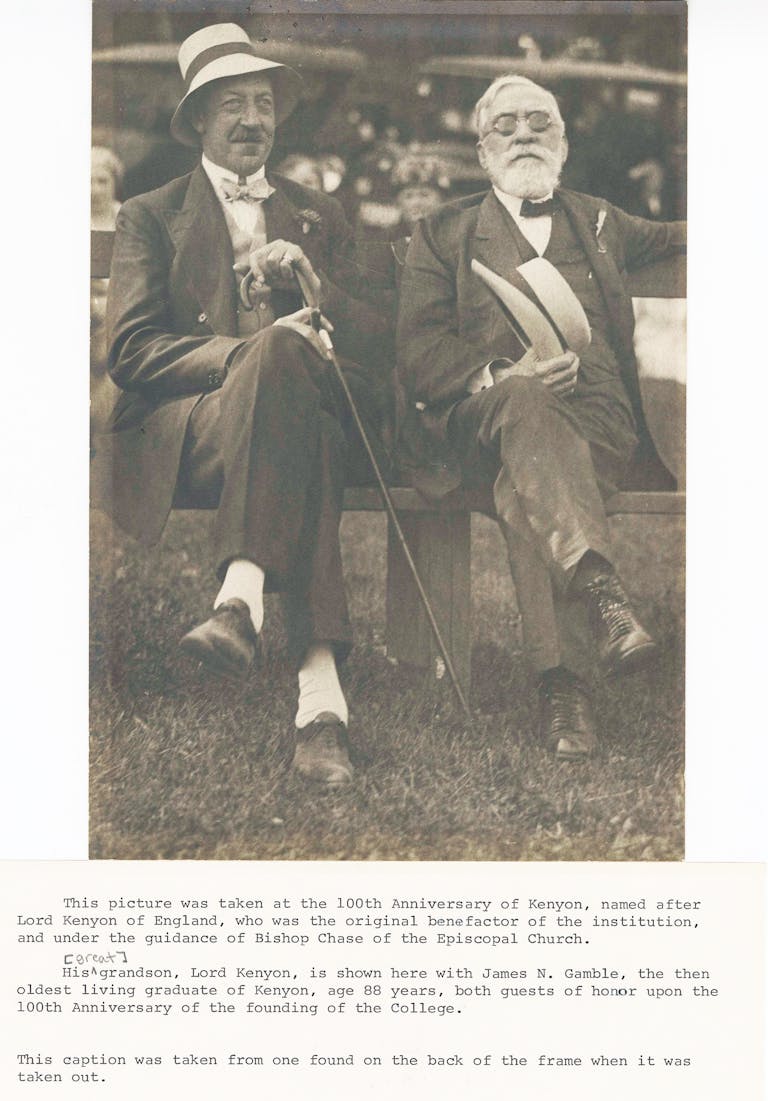

Two generations after George and Philander, the fourth Baron visited Kenyon College for the centennial in 1924, and was quite popular with students. Stamp described him as “hail-fellow-well-met,” extroverted and outgoing, taking the campus by storm.

In England, Taylor Johnson ’83 spent some time with the fifth Baron Kenyon while traveling abroad the summer before his senior year. He was volunteering with the British National Trust and had a week off, so William Dameron, former head librarian at Kenyon, suggested Johnson visit the fifth Baron Kenyon.

“I was like, ‘Really? Can I do that?’” Johnson said. Dameron put the two in contact by way of a letter of introduction. Johnson then wrote Baron Kenyon with an offer to muck out his stables in exchange for a couple days’ lodging. He received an invitation within a week of writing. “I didn’t muck out their stables,” Johnson said, “but they did have some azalea plantings they wanted done, so I did the plantings.”

The fifth Baron picked Johnson up personally from the train station in a Toyota Cortina, the equivalent of a Corolla in the U.S. When Johnson later expressed his surprise to Lady Kenyon about the type of car the Baron was driving, Johnson recalled that she responded, “‘Oh, Taylor, he gave up the Rolls [Royce]. He just smashed it up too much.’” Johnson explained that Kenyon had told him he had always had bad eyesight, “but he really had terrible eyesight by the time I got there.”

Johnson described the fifth Baron as “a bookish man.” Kenyon had a considerable collection of old manuscripts and showed Johnson the original charter for the first Lord Kenyon Baron Dredington with an official stamp issued by the king. The Baron even had a special room made for all of his antique books over the carriage house. Stamp described the fifth Baron as not quite as outgoing as his predecessors, but decidedly “pleasant.”

On Johnson’s first night in the village of Hanmer, Sir John Hanmer, the village’s namesake, threw a cocktail party.

The Kenyons brought Johnson as their guest. “I was hobnobbing with all these titled people,” Johnson said. “They were very interested in this young, American lad who had sailed across the Atlantic. Major Peter Armrod kept saying to me, ‘Well done, you! Well done, you!’”

Over the next few days, Lord and Lady Kenyon took Johnson on tours of a national park and a Welsh town — the Baron Kenyon’s estate is in Wales, though he’s English — and Lord Kenyon would make tea and wake Johnson each morning. After his visit, and until the fifth Baron’s death in 1993, the two remained in contact.

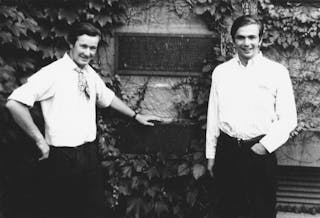

Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, sixth Lord Kenyon, with a friend in 1969 | COURTESY OF GREENSLADE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES

When the sixth Baron Keyon visited the College in 1999, Spaid, as the self-described “expediter” of the College’s planning committee, had to arrange most of the details. “It was such a rare thing that we were able to bring a descendant of one of the contributors of [the] founding of the College,” she said.

It was not actually the first time the Baron was in the United States. According to Stamp, the recent Cambridge graduate and a friend came to the States in 1969 with only $150 in their pockets, thanks to strict currency exchange controls. The two made money selling ice cream in Detroit, which then funded a road-trip romp from the Gulf Coast to Mexico, then from California to New York. The future sixth Baron found his way to Gambier during the summer holidays. As he recounted in his Founder’s Day address, “everybody we met made us feel very welcome and nothing was too much trouble.”

He was even more excited to return. “[Lord and Lady Kenyon] were so game when they got here,” Spaid recounted. “They were in the Bookstore buying all sorts of things that had the Kenyon crest on it. Playing cards, and coasters… and they were going to be taking these back home.”

The College’s crest, though only adopted in 1909, is ultimately derived from the coat of arms of the Kenyon family. (The College motto “magnanimiter crucem sustine” similarly comes from the the family motto of the Kenyons.)

The sixth Baron Kenyon told Spaid of a childhood memory, in which the then-named Kenyon College Choir came to perform at the Kenyon home while on a spring break tour in the United Kingdom. Decked out in crest-decorated blazers, the Kenyon singers stepped off their bus as the future sixth Baron Kenyon looked on. As Spaid tells it, the young Kenyon turned to his mother and asked, “Mummy, who are all of these relatives?”

Professor of English David Lynn ’76 recalled a story in which David Banks ’65 wore a tie bearing the Kenyon crest while riding to hounds (a turn of phrase signifying a fox hunt on horseback) with a group of British nobles acquainted with the fifth Baron Kenyon. Banks lives in London with his wife, so they would often participate in British “aristocratic life” there, according to Lynn. Though the Baron himself was not present for the hunt on his estate grounds, one of his acquaintances was reportedly “outraged” at Banks’ tie. “[The guest] said, ‘You can’t wear that tie. It’s entirely inappropriate for you to wear Lord Kenyon’s tie.’ And David made a point of flaunting it.”

Afterward, the Baron had hardly sat down to tea to welcome his guests when he noticed Banks’ tie. Unlike his disgruntled guest, he seemed enthusiastic to see his family crest on college merchandise. “He was just delighted,” Lynn said. “He thought it was the greatest thing in the world.”

The Kenyon family has, perhaps unsurprisingly, carved out a niche in Kenyon pop culture. The Facebook profile “Lorde Kenyon” has been an active fixture in the social media feeds of many students and alumni, providing commentary on Kenyon happenings in a charmingly antiquated style. The page has existed since 2014, or, if you ask the profile manager, “since I joined Facebook, the year o’ oure Lorde 2014 if I do recall.”

On the page and its community of followers, the profile manager wrote in a Facebook message, “Tis my personal page. The followers are Quite noble, I hath found, even they doth lack my Noble birth.”

The profile manager said that the Lord Kenyon after which the page is named is the second Baron, early benefactor of the College, and referenced the second Baron’s relationship with Philander Chase when describing the process of running the Facebook page. “I let the Spirit of My dear Friend Philander Chase move me,” the profile manager wrote. “And occasionally I do Post in the wee hours under the influence Of a very fine mead.”

COURTESY OF GREENSLADE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES

COURTESY OF GREENSLADE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES

These days, according to Stamp, a noble title does not entail as much for its bearer as it once did. Years ago, the Barons Kenyon held a hereditary seat in the House of Lords, the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, but this privilege was abolished with the reforms of the House of Lords Act 1999.

Johnson described the role of titles in interactions among residents of Hanmer, where he stayed with the Kenyons in 1982. “One thing that was really interesting in England is that the title is very important, even if you’re just a Mr., because Mr. is a title,” he said. “So when I was going around with Lord Kenyon, we would walk into a shop in town, and people knew him, of course, and they’d say, ‘Oh, good morning, m’lord, how are you m’lord, what can we do for you, m’lord?’”

Certainly, the Kenyon name can still open doors for its holders. But the Kenyon family has never been particularly wealthy relative to other British nobility, according to Stamp. Rather, they are known much more for their public service. A May 24, 1993 New York Times obituary for the fifth Lord Kenyon paints a portrait of a man who had devoted his life to supporting the arts, holding board positions as president of the National Museum of Wales and a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery between 1952 and 1988.

With the College’s bicentennial soon approaching, the new Lord Kenyon will likely witness the 200-year anniversary of his family’s relationship to the College. According to Stamp, the College will consider inviting the seventh Baron Kenyon — and the descendants of other early benefactors, whose names can be seen sprinkled throughout buildings and street signs in Gambier — to participate in the commemoration of the College’s 200th anniversary in 2024.