Tom's World

A look into the life of the man who lives and breathes Kenyon.

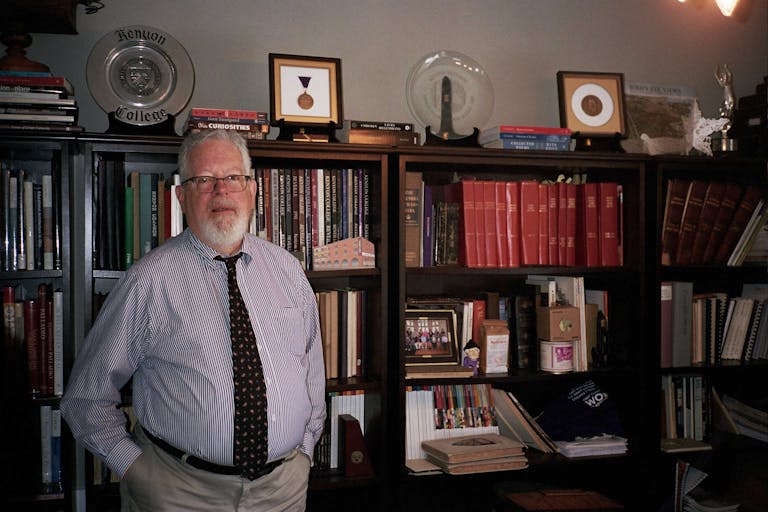

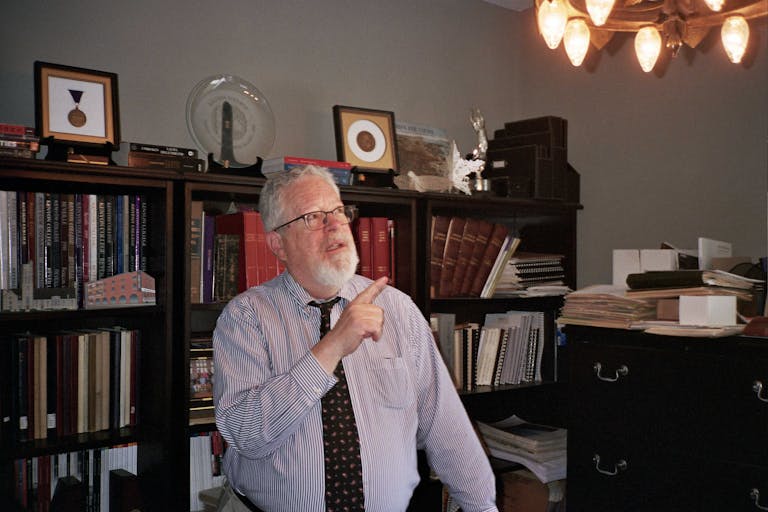

Throughout Tom Stamp’s ’73 home, lining his walls and bookshelves, are various depictions of the alphabet. His decor includes children’s ABC books, alphabet paintings, block letter-themed plates; take a short walk through his home, and you are bound to pass something that begins with an A and ends with a Z. While representations of the alphabet may seem like a peculiar collection, knowing Stamp — the Kenyon College Historian and Keeper of Kenyoniana — it makes perfect sense.

There is a certain historical profundity to the alphabet. Whether it be a book published today, or an archival document from 400 years ago, these 26 shapes and symbols work in conjunction to create any, and every, text. From an early age, this convention enamored Stamp.

“From the very beginning, [the alphabet] seemed sort of magical to me,” he recalled. “That you would have these figures that you would put together to make sounds, that make words, that make books.”

Stamp and I chatted about his fondness for the alphabet, among other things, in our final interview of the semester. We had met almost weekly on Sunday afternoons; by now, I’d become accustomed to his tempered tone and studious pauses between words. I met Stamp my sophomore year at Kenyon; as the Features Editor of the Kenyon Collegian, I’d pester him on a semi-weekly basis, asking him to comment on some antiquated tradition at Kenyon from the 1800s. I was blown away by his breadth of knowledge of the College. It was like speaking to an encyclopedia. Ask him about Kenyon’s involvement in World War II. Or Kenyon alumni who’ve held office. He knew it all. As I’d soon find out, my respect and bewilderment are shared by his friends, students, and colleagues.

To fully understand the scope of Stamp’s vast and comprehensive command of Kenyon’s history, one must begin in Cranberry Township — a rural area in Western Pennsylvania outside Pittsburgh, where Stamp was raised.

Stamp’s journey to Gambier from Cranberry began in his senior year of high school, in the English classroom of Miss Eleanor Stout. Stout took an interest in him, and made it her mission, according to Stamp, to ensure he attended a college that suited his interests rather than simply ending up in-state at the University of Pittsburgh or Penn State. She encouraged Stamp to tour Kenyon, amongst other schools. And so, with one of his best friends in tow, he set out for the Hill.

“Kenyon was one of the later trips that we took because it was fairly close to home, three hours away,” Stamp said. “And I still remember seeing it for the first time… We’re on 229, going through farms and fields… And then, all of a sudden, there are these Gothic towers, rising up from the top of a hill. It was really unimaginable.”

A year later, in 1969, Stamp arrived at Kenyon as a student. That year was a period of monumental change for the College — Stamp’s class, the class of 1973, was the first co-educational class in Kenyon’s history.

Professor of English, editor emeritus of the Kenyon Review and special assistant to the College David Lynn was a first year when Stamp was a senior. According to Lynn, while older students were wary of the idea of introducing women as students on campus, Stamp welcomed the change.

“Some of the older men were pretty hostile to the arrival of women,” Lynn said. “And because Tom was, and is, a great friend and supporter of his women classmates, he stood up for them against some of the male antagonists.”

Lynn met Stamp through Lynn’s residential advisor — the position now known as a Community Advisor — who was a close friend of Stamp. Lynn was instantly endeared to him.

“He was an older, glamorous figure,” Lynn recalled. “Very, very bright and engaged with so many people.”

Stamp’s Kenyon experience was regularly shaped by the intense political turmoil nationwide, namely the highly controversial and unpopular Vietnam War. Stamp joined a group dubbed “Mobe,” or the Mount Vernon Mobilization Committee, in the wake of the 1970 Kent State shootings.

“[It] was something I never in 1000 years would have thought that I would do as a student,” Stamp recalled. “But after Kent State, I think a lot of us did things we wouldn’t have done previously. It was such a shock to the system.”

An 18-year-old Stamp went door to door in Mount Vernon, handing out postage-paid postcards addressed to representatives and senators, asking those who answered to write to their representatives about what had happened in Kent State.

“I have to say that was the beginning of my positive feelings around Mount Vernon,” said Stamp. “I only had one door slammed in my face the whole time. And, certainly, the majority of the people didn’t agree with us, but they were willing to talk about it.”

Perhaps the most meaningful aspect of Stamp’s Kenyon career, apart from the friendships he made along the way (many of whom he still considers his closest friends), were his classes.

“Every year it was like facing a smorgasbord and knowing you could only take four dishes,” he said.

Stamp recalled being intimidated at first by professors’ teaching style and the intellectual strength of the student body. He referenced a political philosophy class — the only political science class he’d end up taking at Kenyon — where the professor would throw questions out and call on anyone, hands raised or not.

“The first time he called on me I was so nervous, my legs shot out under the table and kicked him,” Stamp said. “His response was well, ‘Well Mr. Stamp, I guess that’s one way of looking at it.’”

Stamp graduated in 1973, winning the Dalton Fellowship in American Studies. It would be eleven years — after graduate school at Northwestern, and a seven-year stint at Princeton University in the communications department — before he would return to Kenyon.

Stamp spent years working at Kenyon before becoming the historian, spending time as the Director of Public Affairs, and eventually the Associate Vice President of the College.

Lynn Manner ’07, Kenyon’s retired manager of special collections, told me that when she arrived at Kenyon in 1987, Stamp gave writing seminars to employees on the “Kenyon way to write.” She was blown away by the class, and by his ability as a writer.

“I consider him my writing god. I mean, I know that professor, other professors and other people at Kenyon write novels and books and nonfiction, but he writes every day,” said Manner. “Whenever I have a question about writing something, he’s my go-to.”

When deciding on what he wanted his future at Kenyon to look like, Stamp and then president of the College S. Georgia Nugent met and together created the position of College Historian and Keeper of Kenyoniana for Stamp.

In our first meeting, I asked Stamp what a day in the life of the Kenyon College historian is like. He told me that my question was unanswerable.

“One of the reasons that I’ve stayed here so long is that no two days are exactly the same,” he told me.

Stamp spends most of his days conducting research, often employing help from student associates interested in history and archival research (“I’ve had several really wonderful student associates, and I really missed them this year,” he mentioned to me). It usually begins with a “kernel of information” that he finds noteworthy. From there, he goes down the rabbit hole, using reference materials such as old yearbooks and past editions of the Kenyon Collegian. This research will often end up in an article he publishes, or a talk he gives. A great deal of his work is also finding specific dates; such as, according to Stamp, when Kenyon first did something or when it stopped doing something. “A lot of the questions [about dates] these days come from people on campus, both administrators, and students primarily,” Stamp told me. “But also faculty members, occasionally when they’re looking into departmental history, especially.”

Currently, on the top of his bucket list is the creation of a complete history of the College. To produce this history, he has been using another project — what he dubs the “Kenyon Companion” — as a way to synthesize and organize the immense amount of information that pertains to the history of the school.

“[The Companion] is sort of the history [of Kenyon] in Encyclopedia form. If you wanted to know about a specific trustee from the 19th century, for example, you could go to the Kenyon Companion and look them up,” said Stamp.

Ethan Henderson, who was the special collections librarian and archivist at Kenyon from 2009 to 2013, and is now a rare-books curator and lecturer at Georgetown University, raved about Stamp’s tremendous knowledge of Kenyon-related information.

“With Tom, I mean, the knowledge that guy carries in his head is second to none about Kenyon,” he said. “He can pull out information, and anyone looking for a specific date or stats or names. For the most part, Tom has it in his head and can pull it out… He’s gotten to know everybody, and so he really can paint a full picture rather than just bits and pieces.”

Stamp’s work in preserving and documenting Kenyon’s history extends beyond doing research and finding dates. At times, he has felt obligated to take matters into his own hands to ensure the preservation of College-related artifacts.

For example, around 17 years ago, the College was contacted by the ancestors of Alfred Blake, a member of Kenyon’s first graduating class in 1829. The family had stayed in Ohio for generations and owned a home in Columbus. The family was planning on selling the house, as most of the members lived in England and Australia. They asked the College if they would be interested in purchasing, according to Stamp, generations’ worth of Kenyon-related artifacts, including Philander Chase’s (the founder of Kenyon) old desk. The desk began as Chase’s, and was passed to his nephew Salmon —who later became the governor of Ohio — and then to Alfred Blake, who, by then, was the principal of the Kenyon Grammar School. The College did not have enough money to allocate to the purchase, so Stamp decided to procure everything himself.

“I wasn’t going to let [the desk] slip away,” he said. “It was way too important of an artifact.”

One of the items in the purchase was a pair of Blake’s tiny, wire-rimmed glasses.

“And this is the strangest thing,” Stamp recalled. “I have a really complicated prescription so I could never wear anybody else’s glasses. And I put these on and I could see just fine. Really, really strange.”

While the majority of his work deals in the past, recently, Stamp’s been tuned in to present, keeping tabs on Kenyon’s response to historical events in the now — specifically the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of the Kenyon Student Worker Organizing Committee (K-SWOC), who are petitioning for the formation of the first undergraduate student union in American history. In terms of the pandemic, Stamp notes that the time people spent quarantining in their homes has afforded him a bounty of previously uncovered historical material.

“This is a time in which people all over the country, all over the world, are going through those boxes and boxes of family papers and mementos and sites that have been sitting in the attic or the basement for years,” said Stamp. “And then they send anything related to Kenyon here for us to have.” Stamp has also been periodically documenting the major moments in Kenyon’s response to the pandemic — namely the vaccination rates, and the ebb and flow of quiet periods as cases rose and fell on campus.

Regarding K-SWOC, Stamp has added major events (such as strikes, occupations) to his timeline of historical events on campus. Stamp noted that while he wasn’t able to locate any historical precedents, within the last 25 years, there has been an increased emphasis on the topic of labor on campus across the country, mostly pertaining to graduate students.

“At this point. It’s probably not a good idea for me to declare myself,” Stamp said of K-SWOC’s recognition. “But I certainly do think it’s worth considering.”

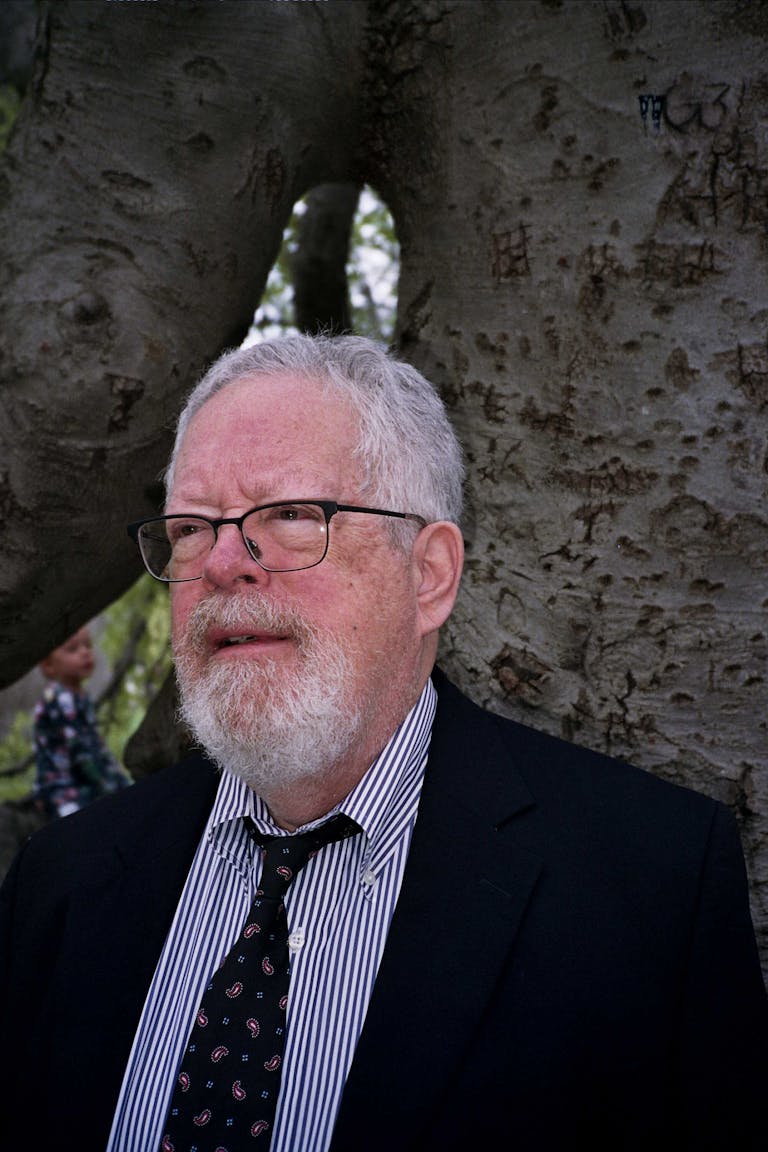

While the majority of the work of a college historian is fairly neutral — in terms of documenting and recording previous events in the College’s lifespan — there’s no question that Stamp has developed an acute and unparalleled understanding of first 200 years of the College: both what it has done right, and what it has not. I asked Stamp if had any concerns about the trajectory of the College. In his answer, he referenced two things that currently trouble him: Kenyon’s trees, and the College’s growing student population.

When Stamp arrived at Kenyon in 1984, the College had an arborist on its payroll. Now, the trees in Gambier are often unattended, and are in need of branch thinning and removal. The issue is not simply an aesthetic one: These treatments, often conducted by an arborist, help keep the trees healthy, and, as Stamp notes, remedy safety concerns that can arise from dead tree branches falling on students.

To Stamp, Kenyon’s beauty emanates from its attention to the minutiae; the tall trees that swallow the campus, its small student body. When we forget what makes Kenyon, Kenyon, we begin to lose the beauty and spirit of the institution.

“You can’t take your eyes off those things and expect the College to remain the special place that it is,” he said.

Despite these critiques, if you ask those who have worked with Stamp, his love of Kenyon is immense. It extends far beyond an academic understanding of the College; it is almost as if Stamp and Kenyon are inextricably bound together.

“He lives and breathes Kenyon. I don’t know anyone who is more dedicated to the College. Sure, there are people who have distinguished titles and awards and everything like that, but no one [more] embraces the ethos of what Kenyon is," said Henderson. “When you think of Kenyon, you think of Tom.”

“I think it goes to the heart of his own personal identity,” said Lynn. “I think that, you know, he identifies with this place so, so, so closely, but I also think it means for him the very best of American higher education. [It’s] a place that welcomes people for who they are, without pretension… It represents for him what’s best about America and best about American education.”

Even Stamp himself has trouble quantifying what Kenyon means to him.

“[Kenyon] means the greater part of my adult life. and even before my adult life — from 17 [years old] onwards. And it means the majority of my friendships, which are very important to me,” he said. “And it’s so much a part of me it’s very hard to sort of think about which parts are not.”

Apart from being the historian, Stamp is an adjunct professor in the American studies department, teaching an annual seminar on collegiate architecture, titled “The History of American College and University Architecture and Planning.” Stamp’s infatuation with collegiate architecture began as a child, when his grandparents would take him along on their visits to his uncle, who was a student at Carnegie Tech, now Carnegie Mellon University.

“I love the buildings [at Carnegie Mellon],” Stamp said. “So, I suppose I can trace my interest in college architecture back to that time.”

Stamp originally planned on majoring in mathematics at Kenyon, in order to go to architecture school after he graduated. Although he ended up changing majors pre-graduation, Stamp used the money he received from the Dalton Fellowship to take classes at the Art Institute of Chicago on architecture. Then, upon arriving at Princeton, he sat in on a few classes on the history of architecture.

It was close to 17 years ago, at the recommendation of Professor of American Studies Peter Rutkoff, that Stamp began teaching his course. Stamp was apprehensive at first, as one of the factors that led him to the administrative route in higher education was his dislike of teaching in the graduate school setting.

“Peter kept after me and said, ‘you know, it’s gonna be a different experience. Now, you’re not the same age as the students you’re teaching,’” Stamp said. “So I decided to do it. And I fell in love with it. It was just a wonderful experience… From really the first class, I went home, and I was so buzzed from the experience that I couldn’t sleep that night. And I still feel that after a good class.”

Trudy Andrzejewski ’12, a former research assistant of Stamp and now a special assistant for development in Cleveland’s Office of the Mayor, specifically appreciated how the class was not just focused on architecture, but rather incorporated a nuanced exploration of the different elements that go into making a campus.

“What I really took to was that it dug deeper into the theory and motivation behind design. So not just what a campus looks like, but what are the principles that kind of are exhibited throughout a campus plan,” she said. “I was really drawn to that introduction of thinking about the ways that our physical spaces, or our physical surroundings impact, then shape our values. And that’s been something that I personally have continued to pursue ever since taking that initial course with Tom.”

After taking the course, Andrzejewski recruited Stamp to be her advisor for her independent study. Since then, her relationship with Stamp has blossomed into a friendship.

“I really think of him as like a member of my family,” she said. “Reflecting on my time at Kenyon, I so looked forward to discussions with him. I mean, really, what the independent study felt like was like a one-on-one seminar. Tom very much paid attention to what sparked students’ interests… To be a little bit more specific, I had no idea what Historic Preservation as a field even was before I started studying under Tom. And I still work in that field today. He wholeheartedly introduced me to what it was.”

However, after 37 years, Stamp will be retiring from his role at College in October.

“I know that come next January, I’m going to probably have at least a few weeks’ worth of depression of not teaching and, and not having those interactions with students,” he told me.

I asked some of those close to him what the College will be losing when Stamp retires.

“It’ll be losing a slice of its history,” Henderson told me. “A connection to decades and decades of told and untold stories. Kenyon’s going to lose its most valuable and most treasured connection to its history.”

“It’s hard for me to imagine Kenyon as a place that Tom isn’t a very critical component of and I think that he will remain that way long after he chooses to retire whenever that may be,” Andrzjewski said. “And I think that’s one of the things that I’ve also cherished and learned so much from him about is how to be an active and meaningful community member. So I think even if he steps away from his role, specifically working with the College, I imagine he’ll remain a valued community member for such a long time to come.”

In one of our meetings this semester, Stamp and I sat on the steps of Rosse Hall, overlooking the construction of the new library; a building that, once completed, will likely mark the first page in a new chapter of Kenyon’s history. I asked Stamp if he had any advice for the next historian at Kenyon.

“To hire more student associates, I think that would be number one,” he said. “I think not only is it essential to completing the work, it’s also important because you’re getting new generations of students interested. Interested in history and committed to keeping it alive.”

His answer perfectly encapsulated Stamp: a practical, humble response, and a total devotion to the betterment of the school and the students who attend it.