The Mistress

“What must it feel like to have a hand on a belly and know that the kicking could mean either a downtown apartment and leisurely weekends or a struggle to keep food on the table?”

My mother shares the story of a mistress one night at dinner. I don’t remember how it comes up, perhaps a question about work or a discussion about young people these days, but something — a word, a phrase — prods at that particular aspect of her day, an ugly blot in her checklist.

“Those young girls, they come from the countryside. Probably the first in their family to come to the city,” my mother says. “They’re unsophisticated…That’s why girls need to be spoiled, so this type of thing won’t happen. So you won’t be tricked.”

My sister, thin and tall and angrily thirteen, scowls and stirs at her rice, piling the little grains into a miniature mountain. I try to make up for her surliness, asking, “What happened, Mom?”

“One of my girls resigned today,” my mother says, placing her chopsticks on her bowl, a crisscross of bamboo across porcelain. “She was a good worker, had a way with customers. Our jeans flew off the shelves when she was there. But you know, it happens too often. She got involved with a customer and got herself pregnant.”

Got herself pregnant. I want to laugh, it sounds so curiously 18th century, something a disgruntled English housewife would say about the help. Got herself pregnant. Suggesting creation as a solo act on the part of the woman, all the shame and all the joy, hers hers hers.

“Gross. Why would you tell such a nasty story?” my sister says.

“To teach you two something,” my mother says. “You know who that man was? A fat old man who owned a share in a coal mine, with a little money and property. And he had a wife.”

“Ew!” my sister says, her nose squeezing up to her eyes, forming wrinkles of disgust. “Even more gross. Why doesn’t she get rid of the baby? I would.”

We used to run up home after school, backpacks bouncing against our backs and straps flaring behind us as we ran around and around the endless spiral of stairs to our apartment. We would scramble for the house keys, hidden cunningly in a pair of red high heels in a shoe box outside, and fling open the door. First, the kitchen — usually Mom left something for a snack (our beloved street food from the sun-browned hands of stolid women expertly tossing foods on greasy iron pans: spring rolls so crisp they cut your mouth, buns spilling with black mushroom filling, potatoes shrunken with oil and buried underneath clumps of shallots and coriander). Then, quick-step to the TV and cartoons: the red-and-yellow carp adventuring in a garishly bright sea, badly illustrated sheep playing tricks on the big bad wolf, teams of kids competing in increasingly ridiculous model race car competitions.

We watched the commercial breaks like they were cartoons, and in our games we imitated the commercials along with the cartoons. The carp might break into a jingle about the benefits of x brand toothpaste, so clean and minty for fish teeth, or the brave sheep might find opportunity to extol the virtues of the newest vitamins, which, along with its anti-aging, anti-exhaustion, and anti-disease benefits, warded off your neighborhood wolves. Mom found it funny until we acted out our favorite commercial.

My sister lay on the sofa and raised herself up, blinking. “Did we start yet?”

“It’s already over,” I said, smiling as benevolently as I could. I couldn’t hold it for long, though, and we both started shaking with laughter, my sister rolling off the sofa and curling into a happy comma on the floor.

“I haven’t seen that one before,” Mom said, her eyes on a stack of papers printed with millions of words. “What’s funny about it?”

“It’s about babies,” I announced, a trickle of pride slipping to my mouth. My sister didn’t even know that. She just laughed because of the doctor’s double-chin.

“Babies?” Mom asked, then all her expression went to her mouth. Her eyes lost their smile-wrinkles and her nose lost its scrunch. The soft lines of her mouth hardened and she said, “Is it an abortion commercial?”

Spooked, I shrugged. When Mom’s mouth dips and a little hard knot forms right underneath the left corner, you can’t know what she wants to hear. Besides, I didn’t know what abortion meant.

“Don’t do that again,” Mom’s mouth said, the little knot tightening.

But of course we do. Her disapproval makes it funnier.

"Don’t say ‘get rid of,’ and of course she’s not going to abort,” my mother says. “She wanted to get pregnant.”

“That makes no sense,” I say. “Why would anyone in that situation want a baby? Does she think the guy’s going to leave his wife for the baby?”

“Of course not,” my mother says. “But the man doesn’t have a son. It would mean a lot to him to have a son, even if it’s by another woman. If it’s a boy, he’ll keep sending her enough money to keep her well-off and her child educated.”

We consider this. What must it feel like, I think, to have a hand on a belly and know that the kicking could mean either a downtown apartment and leisurely weekends or a struggle to keep food on the table? I feel a sudden surge of pity for the unborn child, one X chromosome away from damning or blessing their mother.

“I told her not to resign,” my mother continues. “She might still need a job when this is all through. But she’s young and arrogant and she has the nerve to take risks, so she’s living in an apartment he’s renting and doing everything she can to make sure it’s a boy.”

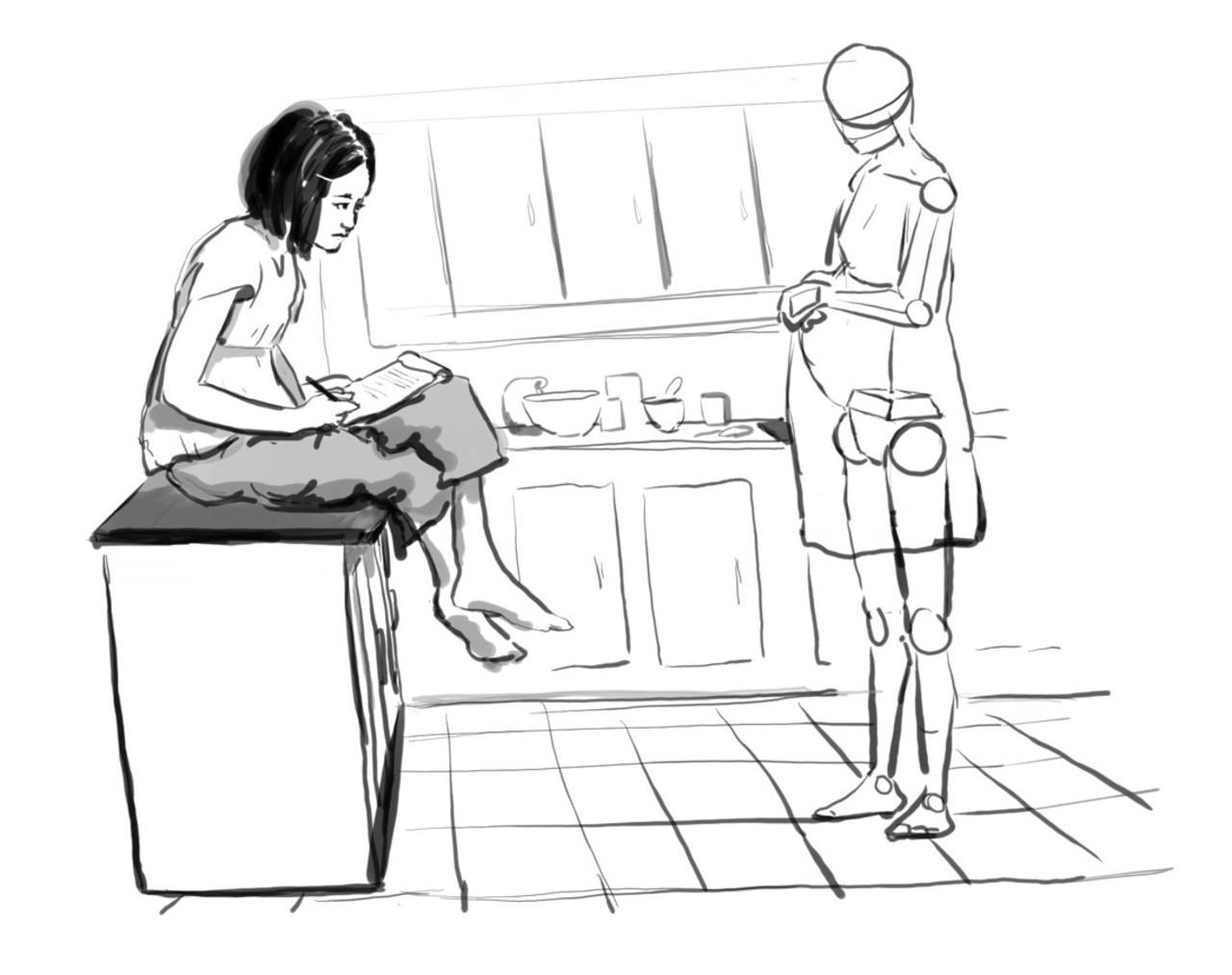

I imagine her, a young woman in fine clothes that she wears like an itch, pacing back and forth in a small sun-lit loft, fingers splayed across her belly, a kitchen countertop spread with herbs and medicines. She might tighten her fingers and curse the day the government outlawed ultrasounds in fear of sex-selective abortion. What does it matter to a little girl embryo if she’s born or not? Perhaps better to die a quiet death in the warm safety of the womb than die a million deaths in the indifferent outside world.

My mother aborted twice. Twice before me, she must have touched her belly and thought, “Not yet.” Because she’s twenty-something, young and a bit not-young, married to a man who spends weeks away at the dinner tables of the rich, drinking himself swollen for contracts, the beginning of a pot-belly showing in his lean frame from long nights of forced alcoholism and black mold creeping onto his teeth from hundreds of offered cigarettes. Twenty-something and turning away from a government-issued job at an insurance company to start her own small business when the country has just opened itself up to the raw gaping maw of capitalism and the dream of clambering to the top, bank accounts and property and something-better-for-your-children just beyond your hands. Twenty-something and not ready, not yet.

But what she says is, “I regret it.”

Why?

“I was selfish.”

Selfish for what? We speak at each other and love each other, our words like a rising flock of sparrows, fluttering dangerously near but never colliding.

I love her. The her now, with spidery lines flecking from her eyes to the soft edges of her face, her hands leathered from dishwashing, floorsweeping, tablescrubbing, guttercleaning, furnituremoving, babybathing, then softened with rose-scented scrubs and imported creams. I love her, the her now and the her then, housewife in worn aprons, businesswoman in pointed shoes, mother in gray sweater. Stretching and stretching and stretching over all the roles expected of her. What regret can there be in staving off more stretch for a little while longer?

And her, loving me, loving my sister, loving my father, loving us, the creatures that warped her into something she wasn’t, she says, “I was selfish.”

"I feel sorry for her,” my sister whispers at night on the bunk bed we share, speaking upward to the darkness.

“Me too,” I say, fixated on the glow-in-the-dark stickers we pasted on the ceiling. “I wonder what will happen.”

“Hope it’s a boy,” my sister replies before turning onto her side.

I imagine her, this unknown woman who had gotten herself pregnant. Early twenties, maybe. Shortish, with a browned face and round nose, dark hair parted down the middle and screwed into a bun. What did she feel as she rumbled away on a bus, clutching her sweaty bundle of money and looking back at her village, one-story buildings of mismatched white tiles and red brick and flat gray concrete, windows pasted with red paper cutouts? And what did she think when she met him, beer-bellied and sweaty, a Visa card in his pocket and all the trinkets she’d never owned, all for her? Did she call her parents when she found out about the pregnancy? Did she lie to them and say how happy she was in the city, how free and independent she was, and how she’ll send some more money next month? And what does she think of the baby? Does she touch her belly with roughened hands and think about the child? The years stretched out for the two of them into a murky future, her and her little boy (not a girl please please not a girl) under the shadow of a beer-bellied man?

Did she think that her life would become a dinner tale for girls living a life isolated from hers, who sat in airy classrooms and studied English, preparing to go abroad for college? Did she think she could be reduced to a story to teach other girls how to be female? Did she think someone else would lie awake imagining her, erroneously and falsely, as if that would give her any of her humanity back?