Accounting for Ambition

Donations only cover about half the cost of campus construction projects. To pay for the rest, Kenyon must take on debt. Right now, the College owes $270 million.

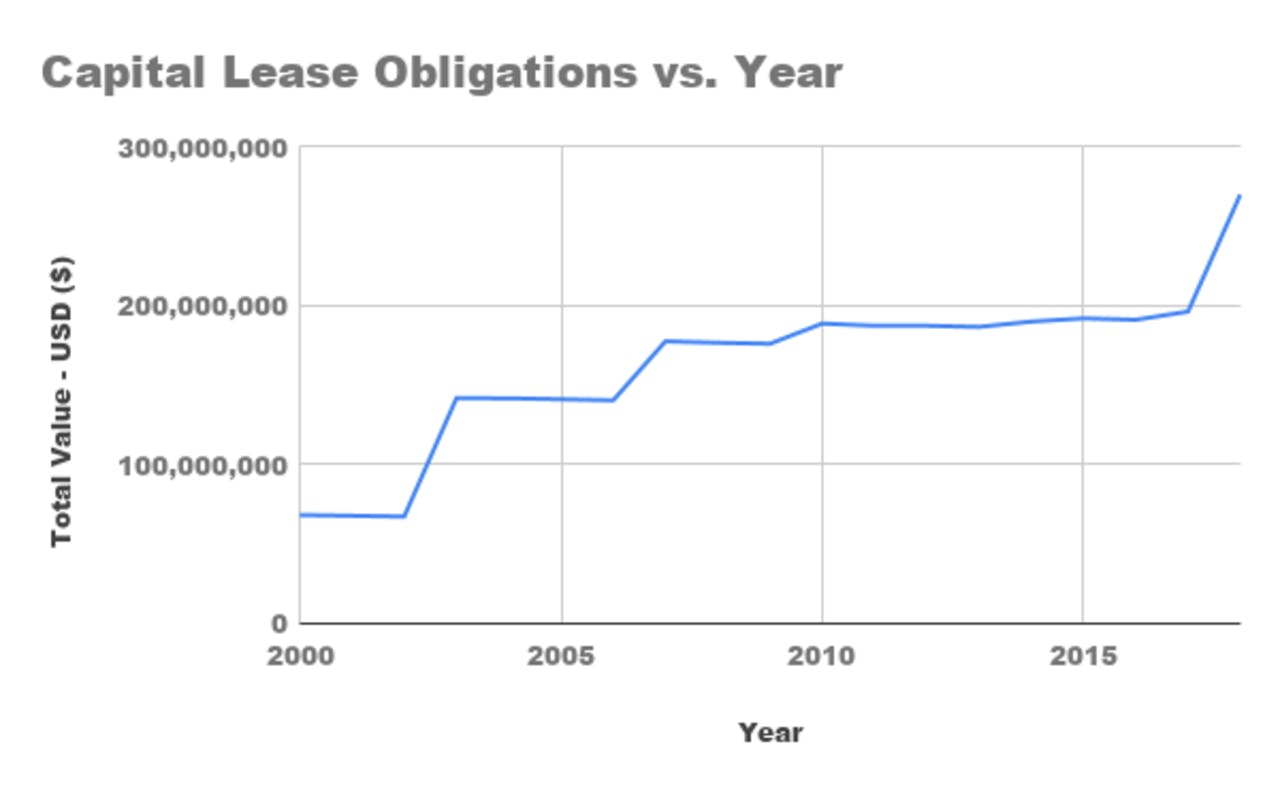

Kenyon is currently $270 million in debt. In 2002, that number was around $70 million.

Todd Burson, Kenyon’s vice president for finance, said this increase is due to the flurry of construction on campus in the past two decades — namely the KAC and the West Quad projects. In recent years, the College has emphasized the impact of large donations on its ability to pursue these projects, but that money only covers about half the cost. The rest comes from a process called debt leveraging that has led to Kenyon’s current financial hole.

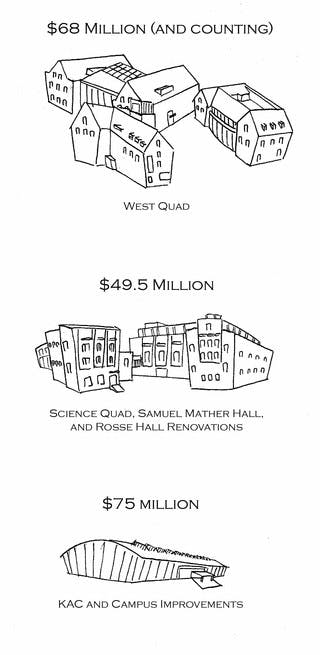

Financial or debt leveraging is the use of debt to acquire additional assets, such as a new building. The way Burson describes it, the College first receives a gift that is tied to a particular project, such as the $75 million anonymous gift that it received in September 2017 for the West Quad project. After that, the College will work with an investment bank to navigate the debt market by issuing bonds. Investors and groups buy bonds because they guarantee a reliable, predictable income stream — the bond is essentially a request for money with the promise of paying it back in full, plus interest, within a fixed window of time. For the West Quad project, Kenyon has already issued $68 million in bonds.

As a not-for-profit institution, Kenyon sells bonds in the untaxed marketplace, meaning it must promise to pay off the debt during the length of the useful life of the asset. For construction projects, the useful life is typically around 40 years.

“As is the case whenever you’re issuing debt, you’re making a judgment about the fact that it will continue to strengthen the institution, the College, such that we will be able to comfortably service [pay back] that debt over time,” Joseph Lipscomb ’87, the chair of the Board of Trustees Budget Committee, said. The Budget Committee approves the College’s annual budget and oversees longer term capital and budgeting decisions, like debt issuance.

For the 2017-18 fiscal year, Kenyon’s audited financial statement revealed a significant uptick in the College’s assets, which rose from roughly $742 million in 2017 to roughly $911 million in 2018. This is primarily due to the $75 million anonymous donation and the cash the College received from selling bonds. As such, this spike is accompanied by an increase in liabilities, explaining the jump in Kenyon’s capital lease obligations (or debt from bond issuances) to the current $270 million.

That may seem like a big number, but Lipscomb said there is no precise way to determine what a healthy amount of debt is. Rather, if the College has a strong financial position overall, then debt is not a cause for concern.

Lipscomb believes the overall financial health of the College is still strong. “It’s just been a very financially well-managed school for the last 50 years,” he said. This creates a predictability in financial results, which allows the Trustees and senior staff to think about how debt would fit into things.

For Burson, an important thing to consider is the College’s ability to supply bonds and the market’s demand for them. “This last bond deal we did… we had people lined up to buy the bond,” he said. “That supply and demand is something you always want to watch.” A higher demand helps the College determine the terms of its debt.

The $75 million gift and $68 million debt leveraging do not fully cover the West Quad project. More fundraising is expected to take place. “It’s going to be at least $150 million for all those projects, but almost all of it is exclusively from gifts and debt,” Burson said.

It goes without saying that $68 million is a large chunk of change. A search through recent history uncovers that this is close to the maximum amount that Kenyon will take out for a building. According to the Ohio Higher Education Facilities Commission, which works with independent, not-for-profit colleges in Ohio to finance the construction and renovation of educational facilities, some of Kenyon’s more notable projects in the past several decades have likewise required significant debt leveraging.

In 1998, the College took out $20.5 million for the Science Quad and renovations for Samuel Mather and Rosse Halls. In 1999, it took out $29 million again for the Science Quad. In December of 2002, the College took on $75 million in debt. A portion of this was for the construction of what would become the Kenyon Athletic Center, as well as other campus improvements.

Burson said taking on this debt makes fiscal sense because it allows the College to invest in some valuable capital (like the KAC or the West Quad) that is arguably worth more in the long run than the interest rate the College is given for the bonds it issues. It also allows the College to finance projects without turning to regular operating cash — the approximately $150 million of tuition and fees and annual kickouts from the endowment that comprises the College’s annual budget.

Lipscomb, too, made this point. Both the KAC and the West Quad project are examples of debt leveraging allowing the College to address current weaknesses of the school. “To the extent that we are offering a continually better educational product, Kenyon’s health will be established for a much longer period of time,” he said.

Interest rates are essentially the lender’s cut of the deal. Assuming the rate of inflation is low enough, interest rates ensure that investors come away with more money down the road than they put into the bond. Generally speaking, institutions with greater financial health have lower interest rates, providing a safe and predictable investment option, while higher interest rates generally offer higher rates of return with a higher probability that the debtee could be unable to service their debt.

Buyers rely on rating agencies to help determine the ability of a bond issuer to pay back those bonds. For Kenyon, these agencies are Moody’s Corporation and Standard & Poor’s Financial Services (S&P).

When the rating agencies assess the risk in buying a bond from Kenyon, they take into account enrollment, retention rates, and the geographical origins of students. Most importantly, they look at those factors that impact the ability of Kenyon, on a fundamental level, to continue to operate as a college. According to Burson, one sign of Kenyon’s health as an institution is the fact that the school pulls students not only from Ohio and the Midwest but also California and New York. This gives bond purchasers confidence that Kenyon’s viability as an institution will not be harmed by economic downturn in one region of the country.

Rating agencies also look at the amount of unrestricted funds in a college’s endowment, which shows how much liquidity the College can rely upon as backup financial resources in a rough spell. For Kenyon, this figure was $217 million as of June 30, 2018. The College’s total endowment was approximately $416 million. Kenyon’s endowment, though smaller than many of its peer institutions, has not handicapped its capital investment projects, Lipscomb said. The College does not consider the size of its endowment much when it chooses to take on more debt.

Last year, when Kenyon went to the bond market to issue debt for the West Quad project, this counted as enough additional debt for Moody’s and S&P to downgrade its rating. Kenyon was rated A1 with Moody’s and A+ with S&P and then downgraded to A2 at Moody’s and A at S&P.

According to S&P’s definitions of these ratings, an A/A2 falls into the same descriptive category as A+/A1. An organization in this category has a strong capacity to meet financial commitments but is slightly more susceptible to changes in circumstances and economic conditions than higher-rated organizations. This rating is still within the typical range for institutions like Kenyon. “A lot of the liberal arts schools that we interact with…you’ll see them in the single- and double-A kind of range. The Denison’s and Oberlin’s, we’re all operating pretty close together,” Burson said.

This downgrade did not have a significant impact on Kenyon’s ability to issue bonds. The downgrade only cost Kenyon four basis points, or .04 percent of an interest rate, according to Burson.

When Burson references Kenyon’s “marketplace” and the capacity for the West Quad project to be a “gamechanger,” he’s referencing the expected return on investment that comes from such capital development projects. That return comes to fruition when more prospective students are attracted to the College and more enrolled students stay at the College because of those investments, which makes measuring returns a little more nebulous. “You have to go into it believing at the end of the day, this is going to enhance our academic programs,” Burson said.

To be willing to make an investment, then, the College has to believe that investment will pay off, irrespective of whether or not that pay-off can be measured. As an example, Burson looked back to the largest undertaking before the West Quad: the KAC.

The KAC, like the West Quad, was the product of gifts and debt leveraging. Alongside issuing bonds, the College financed the project through a $25 million anonymous gift, the largest in Kenyon history at the time.

Burson said this project’s return on investment can be demonstrated through student usage of the KAC. He made reference to the inadequacy of the previous athletic center, a converted airplane hangar known as the Ernst Center. Since the construction of the KAC, participation in varsity athletics has grown from approximately 450 students to 600. About a third of Kenyon students now participate in varsity athletics, which Burson called a direct impact of the facility.

Burson likewise said that it made more sense to tear the library down and start from scratch rather than investing in multi-million dollar renovations. While Olin and Chalmers Memorial Library was outdated and difficult to change, the new library will have flexible office space and technology implementation, such that it can continue to meet the College’s needs not just now, but five decades from now.

“That’s Kenyon’s philosophy with the last couple of big projects — if we’re going to do something, let’s do it right,” he said.

For Burson, this guiding philosophy ties into the interlocking web of plans that the College has developed: The 2020 Plan sets out aspirations for academic life at the College while the Campus Master Plan envisions a campus where the facilities and physical spaces are equipped in such a way to help meet this academic mission. He acknowledged that liberal arts colleges all across the country are pursuing ambitious campus development projects in what higher education news sources have referred to as the facilities or amenities arms race. But, at the end of the day, he roots the decision to pursue these projects in a desire to improve the academic program at the College.

“There’s definitely the awareness of what other schools are doing,” he said. “But what I think most schools do though, is they really think about, what do we need to do to enhance our profile with prospective students.”

Alongside the strategic vision, Lipscomb emphasized that at the same time the College is taking out debt to finance the West Quad, it is also engaged in the largest capital campaign in history, which is set out to raise $300 million, of which $80 million will go to funding construction projects.

Burson pointed out that the increase in net assets from $742 million to $911 million will go down from spending the money to finance the West Quad project. As for the debt, that’ll be with us for decades — the bonds issued for the project do not mature before 2058.