McGuire

The Collegian Magazine’s nonfiction contest winner

"It all started in a small very snooty place called Piedmont." So my grandmother begins her unpublished memoir How Green Was My Volley.

I find it, twenty-seven unstapled pieces of paper, in a drawer in my dad’s desk. I don’t remember what I was looking for. The font is large and the sentences succinct. It maps a time far before mine when my grandmother was young and unattached to children or to a husband or to money. There is a brevity to her prose that I am unable to unpack. It’s difficult to tease out a deeper emotional significance from terse sentences such as “Well … I liked winning.”

______________________

Arvilla’s hands are so small that they can’t fit around any of the tennis rackets available at Mrs. Wallace’s School for Girls and Boys, and so a special racket is cut for her. Miniature, with a delicate handle. Mrs. Wallace’s School has only thirty students and only three walls. A fourth wall can be created by drawing a thick canvas curtain, but the curtain is only used if the weather is especially bad. On the usual cold California days that Mrs. Wallace, a strict, widowed, English woman, doesn’t think worthy of the fourth wall, the children attend classes with thick wool blankets.

The grass on the tennis court is overgrown, and the ground bumpy and uneven. But something inside her clicks when she steps onto the court. There is a certain fluidity to my grandmother’s form, a sort of angelic grace that does not exist in her movements off court. Mrs. Wallace, standing on the sidelines by the net, notices and enters Arvilla into her first tournament, the Kiddie Cup.

“It so happened that I won the Kiddie Cup tournament and at age ten fell in love with the game,” my grandmother writes. She follows this with the enthusiastic declaration: “That is the beginning of my story ‘HOW GREEN WAS MY VOLLEY.’”

All she does is practice, but she loves it. After finishing her school work, mostly Shakespeare (Mrs. Wallace assigns lots of Shakespeare), she goes to the court. Her parents, Tesa and Hollister McGuire, tight-lipped and prudent, don’t quite understand their daughter’s obsession with the game. There is something soothing about the smell of the clay, the sound the ball makes when it hits the center of the racket just right. And the control.

At fifteen, she is ranked the number six junior player in the United States.

She plays in tournaments, traveling with a group of fellow tennis players, among them Maureen Connelly, Pancho Gonzales, and Hugh Stewart. The group members all give each other nicknames. Connelly is the collie, Pancho is the leopard, Stewart is the bear, my grandmother is the seal. She never shares the origins of the nicknames.

______________________

After my birth, my mom insists that my middle name be Arvilla. “I was hoping to win her over,” my mother admits to me later. “It didn’t work.”

______________________

The players are housed in private homes of local athletes. One night, the daughter of the host offers my grandmother some beer she’s stashed under her bed. My grandmother accepts. “We thought that was really being bad. Great memories.”

______________________

It’s nutmeg flavored.” Sophia pulls a travel-sized bottle of vodka from a box of tampons next to her bed.

“Where did you get it?” I ask.

“Upstairs, in the alcohol cupboard.”

“Won’t they know it’s missing?”

“No. They never go in there.”

“Oh.” I was hoping she’d say, you’re right, they probably will notice. We should put it back.

It tastes like nail polish remover and burnt toast.

______________________

In her senior year of college she receives an invitation to go to England. This offer means that she might be accepted to play at Wimbledon. With the support of her English godparents, she leaves school immediately.

She goes by train to New York and then by ship to Liverpool. Her godparents drive her home from the airport, try to show her “as much of England as possible” during the drive. They don’t know that the night before was her twenty-first birthday. “Can you imagine trying to show interest in the ruins of Bath when you cannot keep your eyes open?” she asks.

The year is 1949, and the country is still recovering from the war. There is very little meat and few eggs. Meals consist mainly of bread, potatoes, and sometimes rabbit stew. This is not sufficient sustenance for a growing athlete. “My body was screaming for protein.”

My grandmother regards my mother with disdain. She’s from the wrong coast. She’s Jewish. (Later, when her doctor advises her to do 23andMe, she will discover she is 99.9 percent Ashkenazi Jew.) The brunch is with all of Arvilla’s friends. My mother was invited as an afterthought. The women are WASPs. Their lipsticks are various shades of coral. My mother gets seated next to an elderly man who is hard of hearing.

The china is expensive and there are several utensils on either side of each place setting. On my mom’s plate is a small brown paper bag.

The women sit. My mom peers into the brown paper bag, confused.

“I thought you might feel more comfortable,” Arvilla says.

“What?” says the old man.

“I wasn’t talking to you, Leo.”

“Oh.”

Inside the brown bag is a single everything bagel.

______________________

Nottingham is rainy and Arvilla is cooped up for many days before the tournament, unable to practice. The court is red clay (the most difficult surface to play on) and her performance is poor. She doesn’t know how to slide and on the clay the ball bounces up much slower than on the grass courts she is used to. Her timing is miserable.

The next day the Evening Standard describes Arvilla as the “good looking tennis player from California” but also mentions that “Arvilla was nervous.” Of this observation my grandmother writes, “understatement of the year.” Throughout the tournament a battery of ten photographers follow her every move, changing courts as she does.

She plays a few more tournaments in London, the most memorable being an exhibition match for the Duke of Edinburgh. She mentions that after the match she is introduced to the Duke. She describes the meeting as “..... Very exciting.”

The Dunlop Company offers to endorse Arvilla. They give her free tennis rackets and arrange for her to play in Paris at the French Championships. Before the match she is housed in a glamorous hotel, but after losing, Dunlop moves her to a very inexpensive small pension. “I saw a few things in Paris that I had to ask about. I was very green.”

“Here I am in Rome,” my grandmother begins her next chapter titled, “ROME.”

The players are silent as they follow a wiry man in robes down a hallway in the Vatican to a cavernous stone room. He asks them to please wait, and they do, talking amongst themselves, their voices barely above a whisper. Ten minutes later, without fanfare or pageantry, Pope Pius the XII enters the room. “It appeared as if he was walking on air,” my grandmother writes in a rare moment of poetry.

She is impressed by his small stature. The gentle rounded quality of his face. A delicate figure. She could crush him on the court.

He walks slowly from player to player, learning their names and where they are from, speaking to them in their own language. When he comes to Arvilla he asks her where she’s from. “San Francisco,” he repeats. “I’ve been there. I thought it very beautiful.” He takes her calloused hand in his smooth one. Presses a small medal with his picture into her palm.

She receives an invitation to play at Wimbledon and the tournament board gives her $75 meant to last her two weeks. She stays in the upstairs loft on the fifth floor of an apartment in the bombed-out area of London. The toilet is communal. A glorified closet with pipes. To get to Wimbledon she walks to the fancy hotel where the tennis stars are staying and sits with them in the Wimbledon limo, the Wimbledon flags flying in front.

Teddy Tingling, tennis player, fashion designer, spy, designs Arvilla a dress with an organdy over jacket, and a petty coat of matching fabric. During the same season, according to her, he gives Gussie Moran some lace panties and sees to it that the press knows about it. Ten years later he will dress Billie Jean King.

My grandmother loses to the fourth-ranking player in the world 6-4, 6-4. She tells Wimbledon she can do better and is accepted again the next year. During those games she is housed at the home of the tournament chairman. Her accommodations have no toilet, the chairman’s wife instead points out a chamber pot under her bed.

Arvilla meets Althea Gibson at the tournament. The two are doubles partners. The pressure of the game is intensified by the fact that Althea is the first black woman to be admitted into Wimbledon. After the matches the women stand and talk and watch the other players. They both have oval faces, easy laughs. Despite the racist glare from the eyes of much of the public toward Althea that Arvilla has never felt, the two become friends. Young women, far away from home. They both speak the same, deeper language of the game. The one that comes only after hours on the court, after thousands of swings and serves and hits and sprints.

______________________

2004. The living room. Elijah and Nana and I eat turkey sandwiches and watch the TV. Serena vs. Venus. The finals. Both women are glistening with sweat. Their muscles are well defined, unlike the photos of my grandmother on the court. Serena hollers every time she hits the ball.

“Nana, did you yell?” Elijah asks.

“No. I didn’t yell. We didn’t need to yell.”

“What do you think of Serena Williams?” I wonder if my grandmother can see details about her playing that I cannot.

“She’s too muscular. She’s not feminine. You’re supposed to be an athlete, not a machine.”

______________________

Arvilla spends Christmas in Holland with a family of tennis players. On cold days the family sprays water over the tennis court and goes ice skating at night. The family recently lost their son during the war. He was trying to avoid the Gestapo and was pushed from a train and killed. The rest of the family has existed on very little food and were constantly in fear for their lives. My grandmother encounters many ghosts from the war during her travels through Europe.

That summer she makes it to the third round of Wimbledon.

She tours Europe. After winning mixed doubles with Kurt Neilseen in a stadium court, my grandmother and Kurt ask for American dollars instead of trophies. “The rules were … you cannot accept money for winning … we were all amateurs, but I took it anyway.” I’m sure there could be pages of untold stories found embedded in the many ellipses my grandmother typed.

That year in Wimbledon her matches are all held on court one. She loses to the fourth seed, her first match, and in the mixed doubles she is partnered with Jean Barota. He was the idol of many women in the 1930s but is far past his peak. Of Jean my grandmother writes, “He played to the ladies in the audience but that was about all.”

A year and a half later, she enters a contest run by Joseph Magnin of San Francisco. It is called the Glamour Magazine Travel Award for the Career Women Who Made the Most of Herself and Her Wardrobe. She wins the San Francisco prize: $500 in cash and $500 for a new wardrobe.

She is accepted into what will be her last Wimbledon. Her final game is two and a half hours long. She has two match points in the third set but then loses. When describing this, my grandmother displays a rare show of emotion: “it was heartbreaking.”

The Evening Standard, June 1955:

“On the banks of the Thames at Brisham Abbey 150 foreign players lazed in deck chairs on the lawns and sipped tea. There was boating, archery, golf and tennis. American player Arvilla McGuire was the toast of the afternoon. She fell out of her canoe into the river. Spluttering, her dress clinging to her, she surfaced and swam to shore. There were shouts of laughter from the banks as Miss McGuire scrambled ashore shaking herself like a puppy.”

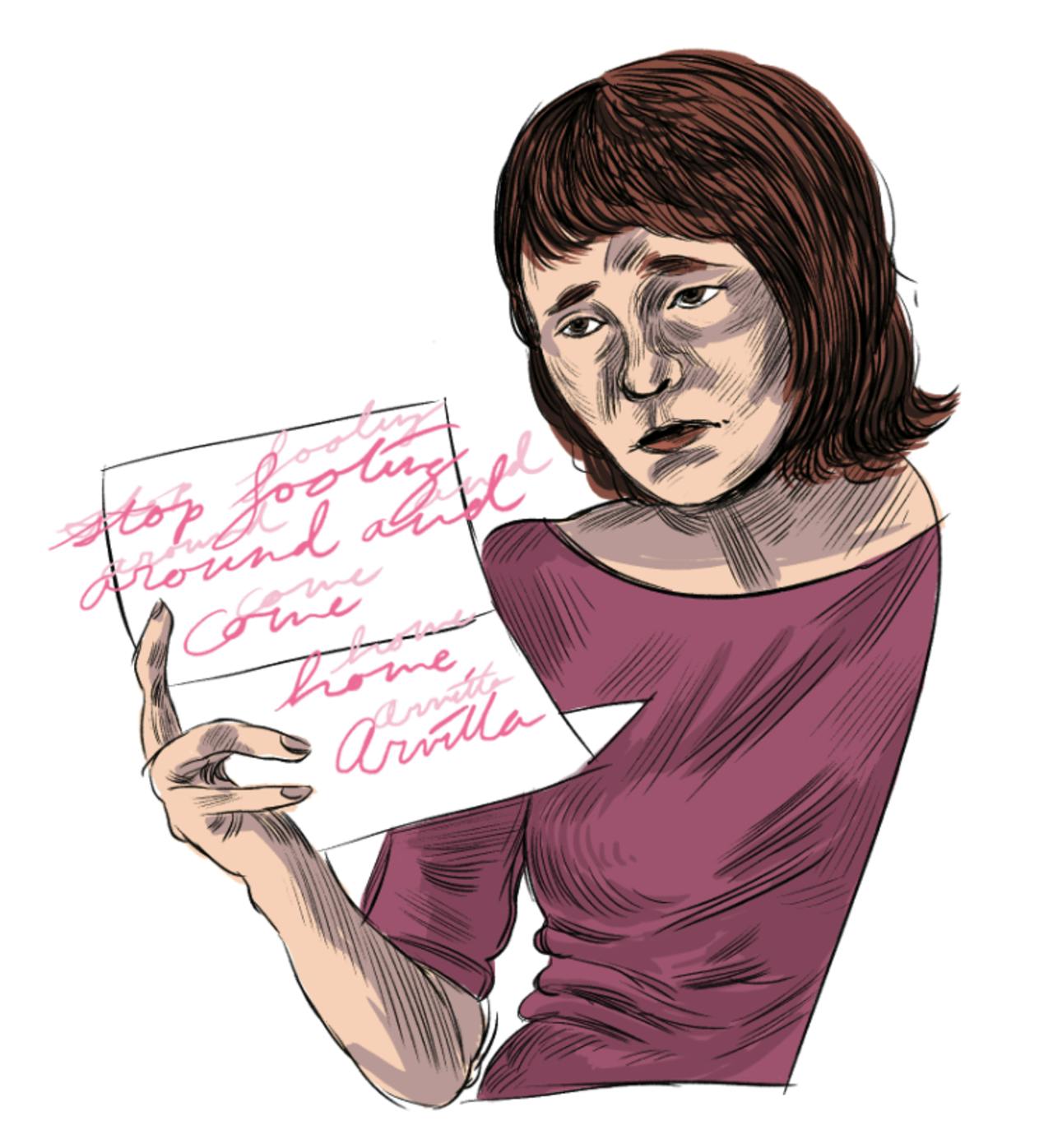

After the game she is invited to go to India for a two-month tour. She hesitates and then, before she can make up her mind she receives a letter from a man she is seeing. The letter says “stop fooling around and come home.” And so she does.

The wedding ceremony has just ended. They stand, the three of them, before the doors that lead into the reception. My father holds my mother’s hand. Arvilla hovers behind them.

My mother turns to Arvilla. “Do you know why a Jewish bride smiles when she walks down the aisle?”

She doesn’t know. “No. Why?”

“Because she’s given her last blowjob.”

At that moment the doors are open and the MC introduces the new couple “Mr. and Mrs. Edward McClure Manning the third.” His words drown out Arvilla’s gasp.

______________________

Arvilla is seventy-four. Stands alone on the deck of the ship in a wetsuit, her short hair already wet from the sea spray. From her vantage point fifteen feet above the water, she can see the dolphins as they glide around the ship. Their backs are a silky silver beneath the waves, and their dorsal fins occasionally cut through the water, fracturing the surface of the ocean, shattering it as though it’s liquid glass.

“Are we all set to go?” The others stand away from the deck, facing the dive instructor. He explains the rules of the dive, going over various hand gestures that he will use to communicate with them underwater. “Okay then. Let’s do it.”

The others form a line by the steps hanging off of the side of the boat, one by one climbing down the ladder to the water. Arvilla doesn’t see the line, doesn’t wait. She leaps off the deck, into the ocean.

______________________

She calls me on the phone one day after she learns that I won first place in my age group in the Westchester Olympic Distance Triathlon.

“I just wanted to tell you good job.”

“Thanks, Nana.”

A pause at the end of the line. She is a woman of few words but seems to be searching for more. “Really good job.”

“Thanks,” I repeat.

“You’ve got the right spirit,” she tells me. “Keep it up.”

______________________

The Stanford Medical Center is bordered by silvery green trees, not palm trees, but those Bay Area, briny, dry grass, Van Gogh trees. The hospital room is warm and there are machines wheezing around my grandmother. Various tubes are threaded through her tissue paper skin. Her skin is as thin as the pages of the bible in her desk drawer.

I ask if she is afraid. She says no. She asks me if I can see the stars. Or maybe she said, have you seen the stars? I don’t know what she means, so I just nod. She asks if I still have the ring she gave me, the one her mother gave her. I don’t know where it is but tell her it is in my jewelry box back home in New York. Then I ask her, if there is something afterward could she give me a sign? Her sigh is a soft smile.

She does not mention the memoir, or any of the stories it contains, even though I ask her about growing up. Perhaps she has forgotten she wrote it or is embarrassed that it never became a published book. But when I do find it, later, it seems polished and ready to be read, as though it was written with me in mind. Just like the earrings I find in a box on top of her dresser drawer with a note above them that reads: “For Dylan.”