The Gambier Experimental College

Winter-Spring 1975

Unfamiliar aromas filled the air one evening in 1982 as the “International Cooking” class finished making the night’s entrée — fettuccine Florentine, flush with ricotta cheese, onions, and spinach. Four Kenyon students, one woman from Apple Valley, two women from Mount Vernon, a faculty spouse, and Alice Straus ’75, then the assistant director of Alumni Affairs, filed out of the cramped Weaver Cottage kitchen, sat down, and dug into the delicious dish. Meanwhile, full of promise, the cheesecake cookies’ mouth-watering smell wafted from the kitchen.

Weeks later, sitting down for the class’s concluding dinner, Straus, the instructor, passed around a bottle of wine to celebrate. For her, the dinner and class “was an opportunity for students to mingle with adults and learn to be adults in their company.”

Though taught in Gambier, the class did not fall not under College auspices. It belonged to the Gambier Experimental College, or the G.E.C., founded in the autumn of 1969 by students Saul Benjamin ’70 and John Flanzer ’70. For $1, a person could enroll in as many classes as they wished. The idea may seem strange amidst the skyrocketing tuitions of today’s collegiate landscape, but the school’s entire premise was to improve access to education for underprivileged kids in Mount Vernon and Knox County. “If you had a question, you should be able to ask it in the company of other people and see where the hell it takes you.” Benjamin said. “You don’t need a college to have ideas.”

Ellen Fineberg, a coordinator for the weaving course, teaches Barrie Byrnes how to use a blackstrap loom.

“Gambier” was a misnomer: the school’s creation grew out of student and faculty discussions about improving access to education for underprivileged kids in Mount Vernon and Knox County. “If you had a question, you should be able to ask it in the company of other people and see where the hell it takes you,” Benjamin said. “You don’t need a college to have ideas.” The founders also decided that cost shouldn’t turn people away; they set the registration fee at $1.

The egalitarian approach worked: Over 200 people registered for the first term. Classes spanned from the oddball (“Supernatural and the Black Arts”) to the academic (“The Thinker and Society”) to the practical (“Batik”). Basements became classrooms, living rooms became lecture halls. Student instructors — lacking a house in which they could gather — often borrowed empty rooms in Ascension Hall.

According to Benjamin, it didn’t matter whether the instructor had a Ph.D. or a bachelor’s degree. “You’re all teaching each other.”

The experimental college also filled gaps in Kenyon’s curriculum. Doris Crozier, dean of the newly-formed Coordinate College, taught “Anthropology” and Professor of Religious Studies Richard Hettlinger taught “Sexual Maturity,” a gender studies course. The College had never previously offered a class on either subject.

The G.E.C. stemmed from an alternative education model developed by Alexander Meiklejohn, an early 20th-century philosopher who founded the original experimental college in 1927 at the University of Wisconsin. Apart from having a common syllabus, the school eschewed all structure in favor of self-directed study.

While Meiklejohn’s ideas failed to spread during his lifetime, experimental colleges started popping up during the 1960s at liberal institutions like Oberlin College and the University of California, Davis.

Benjamin and Flanzer decided that Gambier needed its own experimental college. The G.E.C., Benjamin said, “was an attempt to ask the College, ‘What does it mean to be a community of learning?’” In accordance with Meiklejohn’s ideals, they christened the G.E.C. an “educational laboratory” with no requirement other than the desire to learn.

The first term was a bona fide success, but uncertainty plagued the school’s future. Benjamin and Flanzer were graduating and the school lacked a plan to carry it forward. And amidst the confusion, the G.E.C. lost sight of its goals. According to a brief history of the experimental college written in 1975 by Scott Hauser ’76, “there were virtually no Gambier or [Mount] Vernon residents enrolled.”

Still, it persisted, and the following fall of 1983, the G.E.C.’s coordinators sent out a call for instructors. At the time, Tom B. Greenslade Jr. was a newly hired Physics professor with a desire to share his budding passion for photography.

In his class, “A Short History of Photography,” Greenslade’s students learned to craft pictures using 19th-century techniques like tintypes and stereoscopic photography. Free time was scarce for the younger Greenslade, as he had two toddlers, but he taught the class anyway. “It seemed like the right thing to do. You learn this stuff and pass it on,” he said.

Greenslade’s was one of 11 new classes that term, including Gambier’s first journalism class. The excitement was short-lived, however. The catalogue sent out a plea for coordinators for its Winter ’71 term, but the call for help went unanswered. Barely two years old, the G.E.C. folded.

The G.E.C.’s inaugural term in the fall of 1969 drew over 200 people from around Knox County.

The school often commissioned talented student artists to design the course catalog.

Had Kenyon students not wanted to strengthen the College’s ties to Mount Vernon and Knox County, the G.E.C. would have remained an archival footnote. Reviving it “ seemed like a cool way to bring people together [with] common interests,” said Hal Real ’74, the G.E.C.’s new coordinator in 1972.

The new leaders established a Board of Trustees, populated by both students and community residents. To ensure the school’s continuation, the Board prescribed semester course evaluations and a $5 registration fee to pay for classroom materials and catalogue printing costs. The core ideal remained, though. “[The G.E.C.] was just about exploring the world through lenses that you used and wanting to see through other people’s lenses,” Real said.

The G.E.C. offered 30 classes that fall, including “History of Kenyon College and Gambier,” taught by College Archivist Tom B. Greenslade Sr. The course description promised that, by the term’s end, Philander Chase would signify much more to students than the Bishop who “smoked the ham.”

Class met in the old College Archives, a windowless room in the Chalmers Library basement. Greenslade’s enthusiasm and love for Kenyon, however, banished the dungeon-esque setting, according to Doug Givens, former vice president of Development, who took the course in the fall of 1973. He enrolled on a whim but gained knowledge that proved “invaluable” to his job. The class was so popular that the elder Greenslade taught it every G.E.C. term until his death in 1990.

Givens also taught a class in the fall of 1973, “Furniture Repair and Refinishing.” He showed his students how to strip varnish off an old rocking chair and how to reconstruct a dovetail joint. “The purpose of it was to bring a hunk of furniture in and [we would] put it back in working conditions,” he said. As time went on, the students’ antiques inspired Givens, so he started researching each piece’s origin and style so that the students better understood the history behind each piece of wood.

Every member of Givens’ class hailed from Gambier or Mount Vernon. No Kenyon students enrolled. According to Real, it didn’t matter whether people came to the G.E.C. as a Kenyon student or “a municipal worker in Mount Vernon or a high school kid … what mattered [was] that [they] were going to explore X, Y, Z together.” To further this aim, the school set up a registration booth in the Mount Vernon Square and the Mount Vernon News published an article on the G.E.C.’s efforts.

The good press led to a watershed term the following winter. Four hundred people registered for 34 classes. “Cave Science and Exploration,” “Death and Dying,” “The Grateful Dead,” “Pool,” “Russia, An Overview,” “Small Engine Repair” — the G.E.C. had a class for everyone.

Even for kids. In 1974, the experimental college introduced a children’s program with classes on swimming, origami, piano, and improvisational theater. The coordinators wanted to provide a creative and athletic outlet for kids without art, gym, or music classes at school. “Kids enjoy the interaction with Kenyon students and the people who’ve taught courses have always enjoyed them immensely,” Marcie Simon ’77, the coordinator in 1976, said in a Collegian story on October 28, 1976.

Simon also mentioned in the same article that, “I’m still getting mail from Mount Vernon from people wanting to sign,” after more than 370 people registered in the fall of 1976.

Participation waned, however, as the ’70s drew to a close. In 1979, the school didn’t open at all. It returned the following year, but offered far fewer classes, and its role within the community had diminished.

It survived because, “there was probably always, you know, two or three people like me on campus who liked the idea well enough to give it a go,” Liz McCutcheon ’82 said.

When McCutcheon took up the G.E.C.’s helm her senior year, she was piloting a sinking ship. “It was very tough to get people to sign up for these things,” she said. “Nobody from the town much participated, either.” Indeed, when Tom Stamp ’73, then the director of public affairs, returned to Gambier in 1984, the G.E.C. was “a mere shadow of its former self.”

But McCutcheon wasn’t willing to throw in the towel just yet. “I was 20. I didn’t know how to make something succeed, but I didn’t really know how to give up, either,” she said.

McCutcheon believed in the G.E.C. because of her experience leading a class in the spring of 1980. She and a handful of other Kenyon students drove to the Station Break retirement home in Mount Vernon for weekly discussions about Professor Hettlinger’s book, The Search for Meaning. McCutcheon, the moderator, said, “It quickly became clear that nobody did the readings so we would just use [them] to spark the topic and we would just talk.”

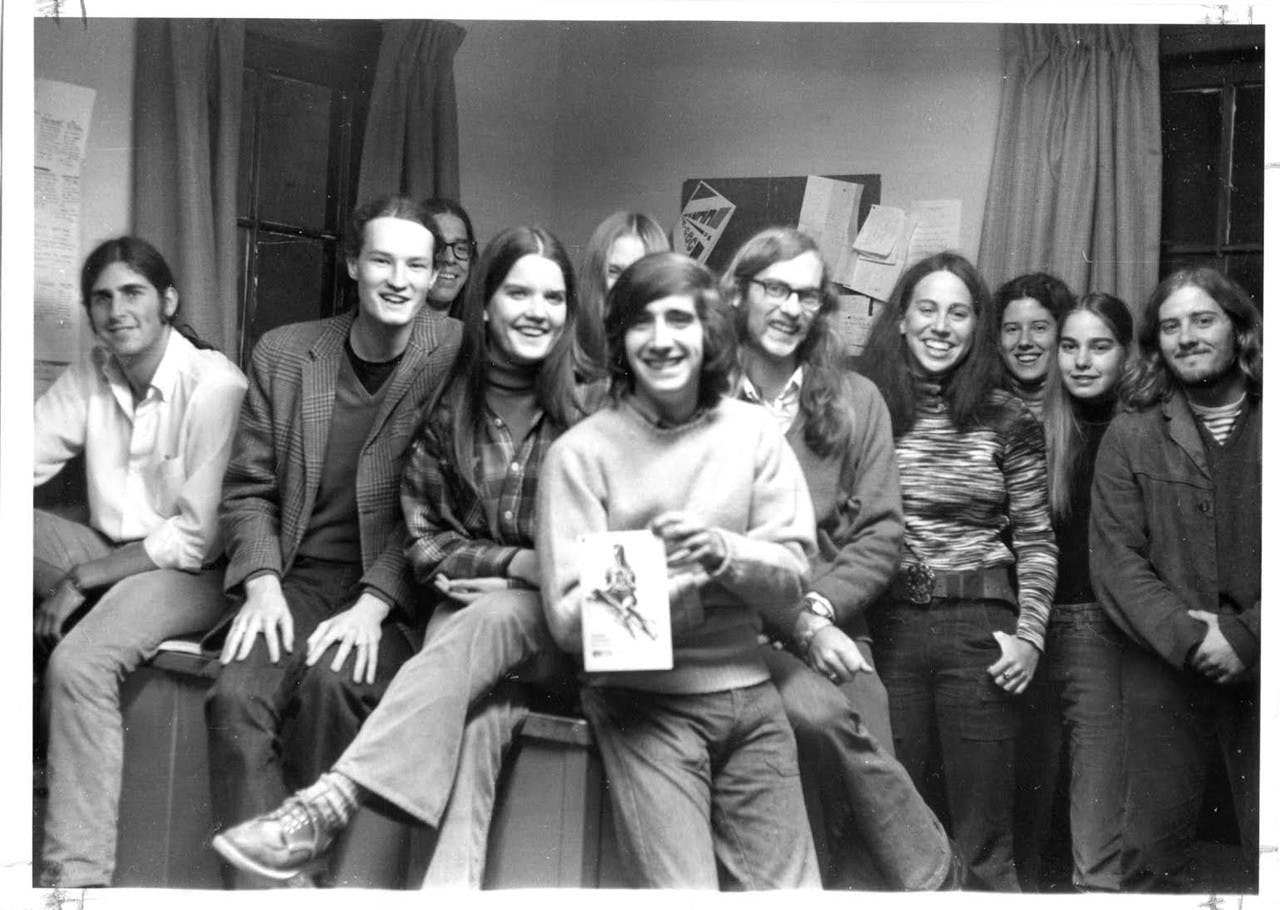

The leadership team behind the G.E.C.’s winter 1973 term proudly show off their catalogue.

The 70- and 80-year-old retirees jumped right in. Family, work, politics, religion, anything was on the table — even sex. McCutcheon laughed and recalled that she and her friends were shocked when one elderly woman said, “‘I don’t think I’d get married again, but I might shack up.’”

The G.E.C. stayed afloat throughout the ’80s on the back of more lighthearted and whimsical classes. “Middle Path Encounters” taught the valuable skill of how to navigate the “unexpected and expected run-ins with lovers, ex-lovers, debtors, loan sharks, professors whose courses you haven’t been to in weeks, and other characters that haunt the path,” according to the course description. A perennial favorite was “A.E.S.A.D.B.S.T.P.T.W. (An Evening Sitting Around Drinking Beer Solving The Problems of The World),” which slapped a moniker onto most Kenyon students’ weekends.

Still, McCutcheon’s prediction was prescient. The G.E.C. faded into irrelevance until, at last, its doors shut in 1990.

Those doors would have remained closed, too, had Barry Lustig ’95 not gone out for a drink one fall evening in 1993. “I was drunk some night at the Cove, and I was talking with a few people that had done all these extraordinary things,” he said. “I was like, ‘I want to know more about what you do, all this cool stuff. There has to be a forum for you to do that.’”

Lustig rounded up some friends who helped him enlist 13 instructors for the “forum.” He called it the “Gambier Experimental College,” despite having never heard of the old G.E.C. In an email to The Collegian Magazine, he downplayed the coincidence, saying, “I’m 1,000 percent certain, though, that the idea we came up [with] was generated independently of past experimental colleges at Kenyon.”

Regardless, Lustig’s present mirrored the past. “There were a lot of tensions between the College and the community,” he said. “[The experimental college] was a way to include everyone in the community: children, townsfolk, etc.”

The 1993 course catalogue was slim but sported a wide range that resembled the G.E.C.’s early years: “Lesser Known Languages of Latin Origin,” “Using IBM Computers,” “Ecological Awareness,” “The Life and Music of Bob Dylan.”

And 20 years before his protests and subsequent imprisonment, the Venezuelan politician Leopoldo López ’93 led a decidedly different movement in Philomathesian lecture hall: “Wine Tasting.” He rallied students together in “a serious attempt to learn something about wine so that people don’t … think that Chateau Collapsible (wine in a box) is the pinnacle of the vintner’s art,” the course description read.

Lustig estimates that 200-300 people signed up for the term’s courses. “Part of the reason the experimental college was successful was that not only did the core organizers take ownership, but the community also wanted to take ownership of it as well,” he said.

Still, the school was, at its core, student-driven. Lose them, and it would collapse again. Which — when the leaders stepped down after the spring 1993 term — it did. Lustig remembers the school persisting, but the Greenslade Special Collections and Archives holds no such records of a continued existence.

This hand-drawn illustration graced the G.E.C.’s spring 1993 course catalog.

While the G.E.C. is gone, its legacy at Kenyon persists. Many of the games and discussions the school sponsored are now official clubs within the College. Tabletop Club hosts Dungeons and Dragons; Russian Club sponsors lectures on Russian history.

Furthermore, those classes Benjamin says Kenyon “should have been offering” 40 years ago — anthropology, gender studies, journalism — are now majors or integrated into the curriculum.

Perhaps the most obvious example of the G.E.C.’s legacy is the Craft Center. It emerged from G.E.C. classes in the early ’70s and practices a familiar formula: Kenyon students and Gambier community members sign up to knit, spin a pottery wheel, or cook Indian food together.

Times have changed, though. Straus pointed out that, “If you want to go knit, you go to YouTube.” Real agreed. “If you wanted to learn about macrame back then, you had to find somebody who understood how to do macrame,” he said.

Persuading students to sign up for additional classes is also harder now, according to Straus. “Students in general are a lot busier.” She believes that, “if [the G.E.C.] becomes that much of a need, somebody will step up and do it.”

Whether or not the alternative school returns, Straus is happy to have participated in it while it lasted. She remains close with Judy Fisher, one of the women from Mount Vernon in Straus’s “International Cooking” class. Both women credit their lifelong friendship to the course.

To Real, it is this possibility of creating lasting connections that explains why the G.E.C.’s multiple rebirths are not a fluke. “I don’t think that anything knocks down barriers better then the sharing of and pursuing common interests and exploring common interests — whether you are in the arts, whether you are an intellectual,” he said.

“Do I still think it could be viable today?” he queried. “Absolutely. For the same reasons, which is bringing people together to build a community.” Lustig echoed Real’s optimism, saying, “I hope students pick up on it again. It was good fun.”

A single slate-gray box stuffed with four folders sits on a shelf in the Archives, waiting.