The Measured Hand

Since he arrived on the Hill in 2013, President Sean Decatur has guided Kenyon through several controversies. Many of them stemmed from a changing idea of inclusion on college campuses. To him, this is growth.

In January, Kenyon’s president, Sean Decatur, appeared on the political podcast The Ezra Klein Show to talk about one of the hottest topics in higher education right now. “Is there a crisis of free speech, of political correctness on campus?” Ezra Klein, the show’s host and co-founder of the news website Vox, asked him. Decatur’s initial response was blunt: “From my view, not at all.”

For years now, national media outlets have been reporting on a rash of events — protests against controversial speakers, dismissals of professors for political speech — that seem to signal a crisis of free speech on college campuses. President Trump even issued an executive order last March that threatens to revoke federal research funding from schools that don’t enforce free speech protections. When Klein wanted to solicit the perspective of a college administrator on the issue, he chose Decatur. Klein seems to know very little about Kenyon (at one point he calls it a university), but he says that a speech of Decatur’s had caught his attention.

For much of the podcast, Decatur discusses the idea of decency, mentioning past examples like the parental advisory labels on Prince’s album Purple Rain or an early-60s statement of student rights and responsibilities at Kenyon that punished “student behavior that offended the sensibilities of anyone on campus.” He states, “Institutions [of higher learning] have always regulated and enforced a set of social norms. It’s just that the social norms have evolved and the people on campus have evolved driving the social norms. What might have been OK 50 years ago, isn’t seen as OK or decent now.” Take blackface for example, he says. When colleges like Kenyon were all white, casual use of blackface was common. Once they had a large enough black population to point out the problems of that behavior, their standards changed.

Klein is fascinated with this analysis. “This seems like a very big deal to me,” he says. Viewed from a different angle, the seeming crisis of speech on college campuses appears more like a series of imperfect but developing attempts by students to figure out something that still confounds the rest of the country: how to navigate an increasingly diverse society.

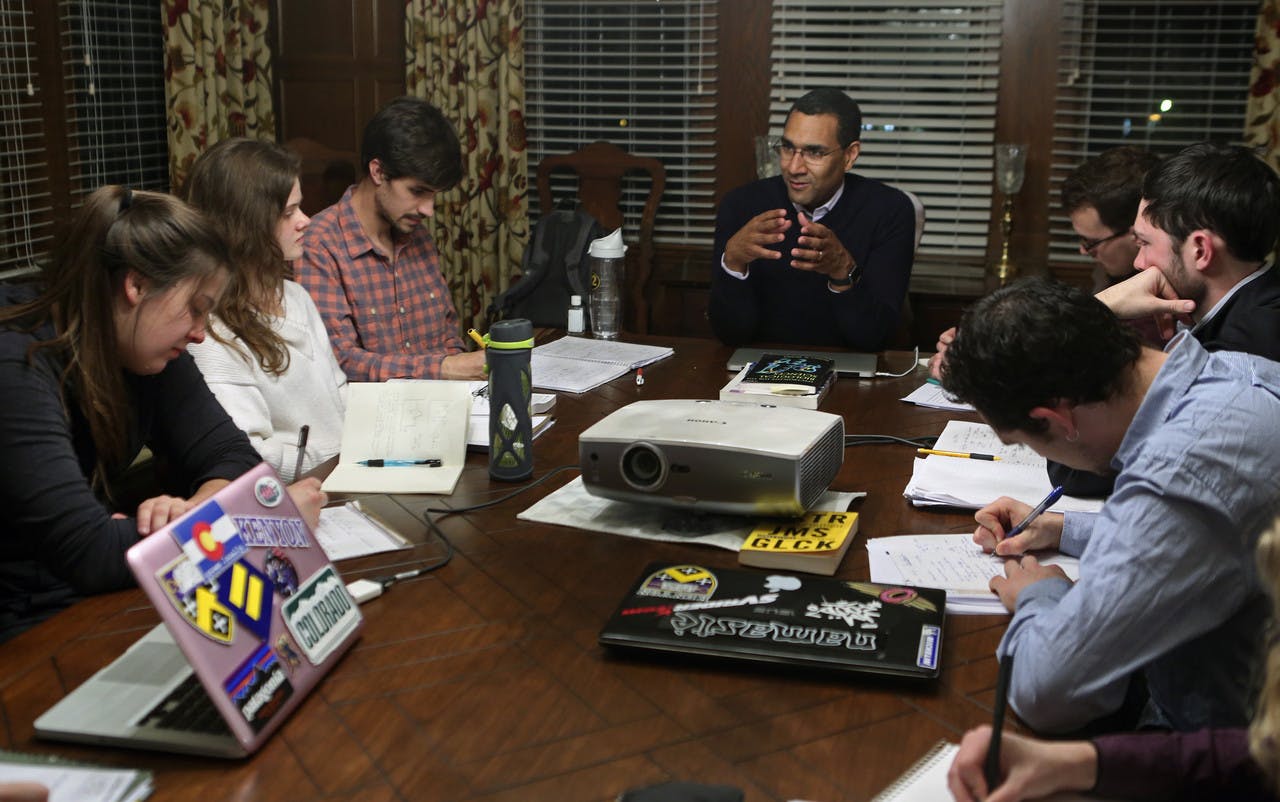

President Decatur speaks during the Our Path Forward launch event. | Courtesy of Kenyon College

The debate over whether or not there is a crisis of speech at colleges is, in part, an outgrowth of a more gradual change that has been restructuring the landscape of American higher education for the last few decades. As colleges have recruited students from a broader range of backgrounds, they have, in the process, changed their ideas about what it means to be an inclusive campus. Developing thought on topics like race and gender has further shifted them away from old norms.

In the spring of 2013, Kenyon announced that Sean Decatur would be its 19th president. For the selection process, the College had used the search firm Storbeck/Pimentel to find a preliminary list of candidates, meaning many of the candidates, like Decatur, didn’t actively seek out the position. He was content as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Oberlin College when he was contacted by Kenyon. “At the time, I wasn’t sure that it was necessarily the right thing for me to do,” he told me last February. After finding out more about Kenyon, he decided he was interested in the challenge.

Since he arrived on the Hill, Decatur, like many other college leaders across the country, has repeatedly faced challenges arising from this developing idea of inclusion. Controversies have popped up around speech, student behavior, and the College’s responses to sexual assault. His thoughtful responses to Klein’s questions didn’t come from unprompted reflection; they were forged in his years of experience running one of these evolving institutions.

What’s more, the College under Decatur’s direction is undergoing massive change in order to compete with peer institutions. Not only is it overhauling its campus with the construction of a new library, downtown, and quad, but it is also restructuring its relationship to its students and faculty. Decatur’s fundraising campaign, dubbed Our Path Forward, the largest in the college’s history, plans to allocate $125 million of its $300 million goal for bringing top talent to the college. Its website lists financial aid, student retention programs, and endowed professorships as part of that process. Programs that support diversity and inclusion are also on the list.

In 2014, a year after Decatur came to Kenyon, the Kenyon Collegian published an article that called Decatur’s plans “undeniably ambitious.” Today, it’s looking more and more like they will become reality.

From second to fourth grade, Decatur attended Case Elementary School, a public school located at the intersection of an Asian-American, an African-American, and an Eastern-European-American neighborhood in Cleveland. Within a few blocks of the school, “there was a polka hall, the Baptist church where I went to church, and all of the Asian food markets,” he recalled. His friends spoke Polish and Spanish at home; some of his classes were partly taught in Cantonese. Almost everyone was working-class. Decatur’s mother, a math and science teacher, raised him and his two older brothers on her own.

In the fifth grade, because of repeated teacher strikes in the public schools, Decatur’s mother moved him to the private Hawken School. It was in the suburbs, about an hour bus ride away from his home in downtown Cleveland. The change was significant. For one, the school challenged him in a way that Case had not. He thrived academically. He also exchanged the ethnically-diverse and working-class environment of his old school for a largely white and wealthy one. (Decatur noted that Hawken has since become much more diverse.) He said that though the academics were better at Hawken, he felt that something was lacking.

Often, he had to switch between the two worlds. In a contribution to Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology, a collection of essays about Cleveland, he reminisces over his rides to and from school. He looks fondly back on the crowded and shabby buses that took him through streets of rundown buildings to neighborhoods of manicured lawns. “What was a daily ritual for me was an exotic voyage for those who only rarely descended from the Heights,” he wrote. When his school wanted to have its prom near his apartment, some parents insisted that it was too dangerous to send their kids downtown at night. The compromise was a sheltered school bus that safely shuttled the students from the suburbs to their prom.

This contrast between an urban, working-class home and a more homogenous, wealthy school gave Decatur a perspective that has stayed with him throughout his career. As an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, he collaborated with a neighborhood coalition in Kensington, Philadelphia, a historically working-class neighborhood, to reclaim public spaces from drug crime and push for more responsible policing. He also volunteered in literacy projects in the local area. It’s amusing hearing him talk about clashing with “the administration” when he felt they weren’t doing enough to support student activism. “I could actually use the word then, before I became a part of it,” he said, catching himself in the middle of a sentence and laughing. At Mount Holyoke College, where he taught chemistry for 13 years, he translated this focus into a race-in-science lecture series. “Some of the big huge problems that I’ve been interested in for a long time actually still exist,” he said, referring to the lack of certain racial groups in the sciences. “It sort of drives me crazy.”

His ability to switch environments is also part of why he feels he can work well in expensive and mostly-white liberal arts schools. “If I hadn’t had this combination of environments during formative times, I may not have felt as comfortable as I do at Kenyon while also, at the same time, recognizing why Kenyon has to change,” he said.

Though fostering diversity was a goal of the College under Decatur’s predecessor, S. Georgia Nugent, it became much more deliberate under Decatur. One of the three priorities of the 2020 Plan, Decatur’s vision for the College that he published two years after becoming president, is to attract and graduate an “academically excellent and diverse student body.” The biggest step he has taken in this direction is his expansion of the old Office of Multicultural Affairs into what is now the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (ODEI). He added another staff member to the two existing ones and greatly increased the budget.

He has also built upon existing diversity initiatives at the College, most notably the Kenyon Educational Enrichment Program (KEEP) that enrolls about 24 students from underrepresented backgrounds at Kenyon each class year. KEEP scholars receive extensive support before and during their time at Kenyon and graduate at about a five percent higher rate than Kenyon’s average. Decatur has been a staunch advocate for the program among the Board of Trustees, securing more of their support every year, according to Jacky Neri Arias ’13, an assistant director of ODEI and the KEEP program director.

At the end of the KEEP pre-orientation summer sessions, the scholars have to give one-on-one presentations about their work to faculty members. Decatur always participates. Throughout the year, he also attends various KEEP events, often walking around and striking up conversations with individual students. Neri Arias recognized the impact this can have on underrepresented students “who need the assurance that they belong on this campus.” Associate Professor of Chemistry Simon Garcia, one of two KEEP faculty co-directors, pointed out, “It is significant that [Decatur] is himself a faculty member of color. He represents a lot to our scholars when he comes to our event and they see, here’s a person who has been through college, has ascended to the professoriate, and, not only that, has ascended to the presidency of a prestigious liberal arts college.”

To be sure, Decatur is not responsible for all the diversity initiatives at Kenyon. Last fall, the College’s faculty revised their handbook to recognize support for diversity when considering staff and tenure-track promotions. And all of the goals in Decatur’s 2020 plan and Our Path Forward campaign came from a series of focus groups he had with students, parents, alumni, and faculty in the beginning of his presidency. Significantly, racial diversity at the College has been gradually increasing since the early 2000s. KEEP itself existed years before Decatur became president and received enough support from Nugent to grow from 12 to 24 students during her time here.

Instead, Decatur’s leadership often feels more like an overarching ethos than a succession of mandates. In many ways, he has acted as a steward for the College, guiding and occasionally nudging it down a path it had already chosen for itself. Because of this, when I think about Decatur’s history of tackling diversity issues and his reputation as a skilled compromiser (the Kenyon News Bulletin announcing his selection described him as having a “collaborative style”), I wonder if the selection committee recognized the ways Kenyon needed to change too. Certainly, Neri Arias observed that, since she was a student at the pre-Decatur Kenyon, “the conversation and the climate has changed drastically.”

President Decatur occasionally teaches classes in the chemistry department, like this one in spring 2016. | Courtesy of Kenyon College

As a prospective college student, Decatur chose Swarthmore over Harvard University, which he had gotten into early admission. A campus visit made up his mind. “I fell in love with Swarthmore much in the same way I hear people falling in love with Kenyon,” he said. “I realized this was a place I could imagine myself, and that made a really huge difference.”

He quickly became enamored with the liberal arts. As a first year, he was set on becoming an engineer and took a set of courses that would prepare him for that track, yet one of his favorites ended up being a class in classics. He had taken it to fulfill a diversification requirement. Besides challenging his writing and thinking abilities, it awoke him to the “deep personal satisfaction I got from studying a broad range of areas.” He would eventually go on to concentrate in Black studies — he still likes to reference authors like Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Morrison — and complete one of his theses (he did two) on the history of African-American education in Cleveland.

His next decision — to follow the pre-med track — also quickly changed. In his second semester, Decatur became close with his organic chemistry professor, who encouraged him to major in the field and become a teacher’s assistant in the chemistry labs. At the same time, an english professor introduced him to a campus program funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation that promoted students from underrepresented backgrounds to consider careers in academia. The combination of the two experiences led him to want to get a PhD. “Certainly, I feel like I’m the product of really good faculty mentors,” he said. “I was also the product of programs that were aimed at supporting students and giving students opportunities … I feel strongly that those are things that make a big difference.”

By the time Decatur graduated with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry, he knew that he “wanted to spend the rest of my career working at a small liberal arts college.” He immediately started graduate school at Stanford, where he got his doctorate in five years, then went directly into a position as Assistant Professor of Chemistry at Mount Holyoke.

When describing how he approaches his job as president of Kenyon, Decatur sometimes looks back on his own undergraduate years. He compared running a college to running a lab. “There are literally a thousand details of things going on at any given moment, much of which is totally unglamorous.” What drives him through the tediousness is always the larger goal. For his other undergraduate thesis, that goal was curing cancer. More precisely, he wanted to encapsulate DNA-binding water-soluble porphyrins in membranes that would then act as drug delivery devices. He said the project was conceived “in that way that only a college sophomore can think. Like, ‘Eh, sure there are many people who have been trying to cure cancer, but none of them have really figured out what I have.’” He didn’t quite hit his mark, but, similar to the task of improving Kenyon, “there were all of these things that then had to come together that I would not have been motivated to do if I did not have this larger goal.”

What exactly is Decatur’s larger goal for Kenyon? For one thing, he is committed to the liberal arts. He frequently praises its philosophy of education in newspapers, speeches, and his own blog. “An education that is all about learning how to think, learning how to communicate well, having the opportunity to think about big ideas … I think it’s incredibly important that we preserve this at Kenyon moving forward,” he said. He sees his efforts to change Kenyon’s demographics as strengthening that liberal arts tradition. “Who is in the room having the conversation about those really big ideas matters,” he said. “The more voices that are included in a discussion, the more different perspectives, different backgrounds, the more ideas are generated, and I think everyone’s learning and understanding gets better.”

On top of this, another $60 million from the Our Path Forward campaign is allocated to help prepare students for their careers after college. This includes support for internships and student research. In a way, it is an extension of the kind of intimate opportunities a small college can provide and that he received at Swarthmore. “I think we need to be attentive to supporting our students as they take what they learn in the classroom and begin to put it into action in some way,” he said.

Many of these goals aren’t unique to Kenyon. Small liberal arts colleges across the country are working to diversify their student bodies and increase support for students outside the classroom. What does differ from institution to institution is the local environment, including the college’s unique identity and past, and its leader.

President Decatur in the basement of Cromwell Cottage, which suffered smoke damage after a fire last December. | Ben Nutter

President Decatur is not an imposing figure. When he’s talking, he has a way of scrunching up his eyes and tilting his head down as if he’s a little embarrassed about what he’s saying. His expressions are naturally kind, yet as soon as he speaks, it’s easy to see the measured thought put into his words. He excels at turning small talk into genuine conversation. Garcia noted, “It doesn’t take long to warm up to him.” Vice President for Student Affairs Meredith Harper Bonham ’92 observed, “With a different personality, his intellect could be intimidating, but because he has this very genuine folksy quality about him, it makes other people feel very much at ease.” Students have playfully nicknamed him “D-Cat.”

There is very little about Decatur that feels performed. At a talk with the Alumni Council last February in Peirce Hall, he started off by giving an overview of the College’s recent successes and changes, then brought up his campaign. Before he said anything about it though, he joked, “I imagine that somewhere there is a log of presidents — because all presidents are in some sort of campaign — who don’t mention their campaign goals in a talk.” He admitted he didn’t want to be in the log. After about 10 minutes, he looked around the room and caught his breath as if he was glad to be done with the spiel, then shrugged his shoulders and said, “That’s all I have to say.”

The moments when Decatur doesn’t have to play the presidential role are when his humor and geeky interests really come out. Last year, Juniper Cruz ’19 asked Decatur to join her all-students-of-color Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) group after hearing of his love for role-playing games. He eventually joined them for a three-hour session, assuming the role of a “demonic cat wizard” named Book. (Players create their own characters in D&D, including their names, powers, and moral alignments.) His alignment was chaotic evil.

At one point in their adventure, the group had to infiltrate a correctional school for traditional D&D monsters, like goblins and orcs. “It was like some sort of prim and proper correctional school,” Cruz said. “It was terrible.” They were breaking in on the day of what she called “the fantasy equivalent of a debutante ball,” and needed to create a distraction in the dance hall. One member of the group suggested spiking the punch. Decatur suggested poisoning it. “D-Cat’s character would do anything to get to his goals,” Cruz recalled.

In real life, Decatur is much more sincere. On a chilly Friday morning, I accompanied him on a tour of Cromwell Cottage, the residency of Kenyon presidents, which he and his family had to move out of in December because of smoke damage from an electrical fire. He was inspecting the restorations that had been accomplished so far and looking over the items that couldn’t be cleaned. If he didn’t want them, they would be tossed.

He met me on the porch wearing all black, a pair of sweatpants, a down vest, and a sweatshirt bearing the logo of the Men of Color student organization. A small beanie blocked off any view of his hair. (Later, when we left the house, he admitted he had to go and change into more “presidential” attire for the rest of the day.) After walking through the repainted hallways, we descended into the basement where a few bikes and some boxes of smoke-damaged belongings were stored. He sorted through them, making little comments about each item — art projects from his kids, old costumes, photos from an exhibit that his wife, a history professor at Oberlin College, had curated. They all had to be thrown out. “It’s a bit sad losing things like baseball mitts, but I don’t think they’re cleanable,” he said with a note of pain. At one point, he encountered his son’s pre-algebra textbook and decided to keep it, remarking wryly, “he will be delighted that we saved his textbook.”

Upstairs, another set of boxes was lined up along the wall next to the kitchen, where the fire and the heaviest damage had been. Everything inside the room was too smoke-damaged to be saved. I spotted a large stack of board games in the corner and exclaimed, “Oh! Look at all those versions of Catan.” I paused and realized what that meant. “Wait, do you have to…”

Decatur looked up from a box he was holding and gave a disheartened nod. “Board games may be the saddest loss,” he said, “that and cookbooks.” The books in the box he was holding had turned brown and curled at the edges.

President Decatur with a box of his family’s smoke-damaged belongings in Cromwell Cottage. | Ben Nutter

One of his most popular blog posts reflects on taking care of his aging mother. He had recently placed her in an assisted living facility. “After a couple of years of checking in on her in Cromwell each evening, I remember those days with happiness, tinged with a bit of sadness for what has been lost, but in deep appreciation of what we had and have,” he wrote. Many alumni approached him afterward and said that his experience had resonated with them. “One of the things I value about being in a community like Kenyon is that we are here to get to know each other as people and as individuals who have lives that are more complicated than they may seem on the surface,” he said.

Though he’s spent much of his life on small liberal arts campuses, Decatur said there’s something different about Gambier. “If you asked me six years ago, I’m not quite sure I would have fully understood until coming on campus and talking to people and living here, how important the relationships that people have with each other, with other students, with faculty, with staff are, and how much of the energy and success and sustainability of the institution relies on those relationships.” He marveled at all the small interactions he has with people in the Deli, the post office, and, of course, Middle Path. “The design of the community almost fosters those types of intimate connections,” he said. “It’s not that I feel that I know everyone by name — you sort of reach a point where every year you recognize everyone and feel a connection to people that you just pass every day.”

Perhaps for all these reasons — his personability, his eclectic interests, his sincerity — Decatur is almost unwaveringly popular at Kenyon. There is plenty about the College and its recent decisions that have upset the various members of its community, yet none of that discontent seems to land on Decatur. “I’ve never worked with a president who has been so universally well-liked. Even in the midst of controversy,” Bonham said. She has been working in college administration for 20 years.

This is not to say that Decatur toes a neutral path. The Ezra Klein podcast is just one example of his willingness to weigh in on some of the hottest debates in higher education. Often, he responds to controversial campus events with blog posts that make clear where he stands. Neither is he merely a figurehead. Bonham marveled at his ability “to assess situations and get to the heart of a matter with remarkable rapidity and accuracy.” Mark Kohlman, the chief business officer at Kenyon, said that even though Decatur is not a micromanager, he still deeply understands every issue that the College faces.

The secret to his ability to stay on people’s good sides may have something to do with the sheer difficulty of holding a grudge against him. His characteristic combination of thoughtfulness, integrity, and optimism warrants his conclusions a degree of respect, even if you disagree with them. And, in all his presidential glare, there remains a side to him that is just plain likable. Before I left her office, Bonham stopped me and asked if I knew about Decatur’s picky food tastes. I told her I did not. “He has a bit of an addiction to cupcakes,” she said, smiling. “We joke that he has the palate of a 12-year-old boy.”

Last spring, Kenyon experienced a controversy that forced it to confront the same issues dominating the rest of higher education. On January 31, 2018, Playwright-in-Residence Wendy MacLeod announced that she was canceling her play The Good Samaritan, which was supposed to premiere at the Bolton Theater on April 5, after a draft of its script had been criticized across campus, particularly among the College’s Latinx community, for its representation of a Guatemalan minor and its treatment of topics like race, class, and sexual orientation. The outcry against the play and MacLeod’s subsequent cancellation of it sparked heated debate within the College.

About a week later, the story found its way to national and far-right media outlets that frequently paired it with news of a Whiteness Group on campus, a student-led space for white students to constructively discuss issues of race, like white privilege. The combination of the two, coupled with coverage that often simplified or misstated the facts, drew a barrage of outside criticism to Kenyon. For many, the events fit into a narrative of increasing radicalization and free speech suppression on college campuses.

Here was a major test for Decatur’s vision of Kenyon. Both the outcry against the play and the formation of the Whiteness Group are outgrowths of the College’s changing demographics and ideas of inclusion. I doubt that The Good Samaritan would have met as much resistance in the more-racially-homogenous Kenyon of a couple decades ago.

But, as some people pointed out, those new values seemed to come into conflict with the College’s traditions. In a February 1 panel and discussion on the play (from which MacLeod, who was originally supposed to attend, withdrew), Professor of Political Science Fred Baumann argued that the response to the play “was the end of liberal education at Kenyon.” Alumni lamented the damage to the reputation of MacLeod, who has a long history with the College, in letters to the Kenyon College Alumni Bulletin. And one commenter on the Kenyon Collegian article covering the play’s cancellation wrote, “This alumnus is appalled at the behavior of these Red Guards and their faculty backers who degrade what was once a gem of a college.”

A year later, Decatur reflected, “It was a crisis of the campus community that I think we failed on a few fronts. When it came to really being challenged about how can we as a community talk about things that are very personal and deeply felt and challenging, in the end, I think we didn’t do it very well.” In a February 7, 2018 post on The Kenyon Thrill, he unequivocally supported the work of the Whiteness Group. It was the conversation around The Good Samaritan that he was less proud of. A week after MacLeod canceled the play, he published a blog post that criticized how campus dialogue had turned from discussion of the play to discussion of the playwright.

Still, he made it clear that he saw both sides of the debate, praising the work of Latinx students in pointing out the limitations of the play. “I cringe whenever I hear anyone use the phrase ‘snowflake’ to describe students who speak out when they feel pushed to the margins by an institution,” he wrote, “these students aren’t snowflakes, but rather icebergs, with depths of strength and resilience, and I respect the courage it takes to speak openly and honestly about one’s feelings.” The challenge, for him, lay in balancing these new voices on campus with the same values of constructive discourse.

Decatur admits that it will be a slow process. If the future he envisions — a Kenyon that maintains its liberal arts traditions while adding more voices to the discussion — is to become a reality, he will have to continue thinking about these issues. At the end of his blog post, he stressed, “In the long term, we will be judged not on the disappointment that many are feeling right now, but on the way we respond and the way we move forward with a direct conversation about difficult issues.” He elaborated on this idea in the summer 2018 issue of the Kenyon College Alumni Bulletin, which focused on issues of diversity at Kenyon after the College’s rocky spring semester: “The ultimate stage of a diverse and inclusive college is where a range of students is brought in, and all — including the institution itself — are challenged and changed in the process.”

For me, one of the most interesting moments of the Ezra Klein podcast is when Decatur acknowledges the way a short institutional memory affects Kenyon’s ability to learn from these controversies. He points out that a fourth of Kenyon’s current student body has no memory of the events, another eighth was studying abroad at the time, and the rest have had an entire summer to lose interest. “You get this episodic burst of conversation and discussion in a moment that then disperses,” he said. “What we’ve been struggling with a bit is, how do you sustain that over time in some way so that you don’t just reproduce the same thing in one year or two years?”

I’m fascinated by this remark because, even though it feels frustrating to me as a student, it also feels true. The dialogue sparked by The Good Samaritan has largely died down since last year. With so much student turnover, it seems to me that one of the surest routes to meaningful change at Kenyon is from above.

In our last interview, Decatur reflected on the difficulties of preserving Kenyon’s core traditions, many of which began in eras with much different values, while continuing to make it a stronger institution. He said one of the biggest responsibilities of the College right now is figuring out “how do we actually do exactly that?”

“That’s your job, I guess,” I said.

He laughed. “Yes.”